April 2015

Japanese Cuisine Around the World

Japanese are introducing their country’s cuisine in different countries around the globe. In this year’s annual report, we introduce Ryuko Abe, managing director of AHT International Limited, who shares with us his extensive experience and contributions in promoting an understanding of Japanese cuisine in Hong Kong for over 40 years.

Ryuko Abe

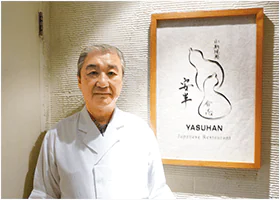

Born 1954 in Hokkaido. Mr. Abe’s career began at Tokyo’s Shinbashi Kanetanaka restaurant; he moved to Hong Kong in 1974, where he worked for 10 years at the Teppanyaki Restaurant Okahan. From 1985, Mr. Abe served as general manager of Kanetanaka restaurant in Hong Kong, and in 1992 opened his own tempura restaurant, Japanese Restaurant Agehan. In 2002, he founded AHT International Limited and proceeded to open Ramen Shop Sapporo, Ramen Shop Hakodate and Ramen Shop Otaru, followed by specialty restaurants Yakinikuya Kinzan (Japanese-style barbecue), Teppanyaki Restaurant Rin and Japanese Restaurant Yasuhan. In 1983, he became a member of the international gastronomic society Chaîne des Rôtisseurs, and in 2013 received the Minister’s Award for Overseas Promotion of Japanese Food from the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

I have loved eating and cooking since I was a child, and I knew I wanted to be a chef. After I graduated from high school, I went to a professional training college for cooking, and around that time I became interested in going abroad. I wanted to test myself while I was still young. I was working part-time at a restaurant, and my boss there told me about Kanetanaka, a high-end Japanese traditional restaurant that was setting up shop in Hong Kong. He said, “If you want to go abroad, go to Hong Kong,” and I immediately fell in with this idea. After I graduated, I got a job at Kanetanaka’s main restaurant Shinbashi Kanetanaka, and in September 1974, I was transferred to Teppanyaki Restaurant Okahan, which Kanetanaka ran in Hong Kong.

Food Culture Surprises

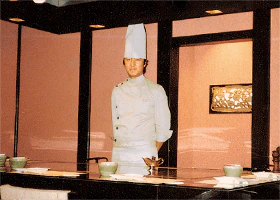

Teppanyaki Restaurant Okahan

I went to Teppanyaki Restaurant Okahan as assistant master chef. Later I became head chef, then restaurant manager. Teppanyaki Restaurant Okahan not only served teppanyaki, but also sukiyaki, shabu-shabu, udon-suki and sashimi. One thing that surprised me about Hong Kong eating habits was that, instead of dipping their super-fatty tuna (o-toro) sashimi in soy sauce, diners ate it with XO brandy—I guess because of its disinfectant properties.

Going Independent

In June 1992, I went into business for myself. I found a basement-level location at the Furama Hotel in Hong Kong’s Central district, and opened a restaurant called Japanese Restaurant Agehan that specialized in tempura, which was deep-fried right in front of the customers—something that was then quite new in Hong Kong. Preparations to open the restaurant were going smoothly until suddenly, only a week before opening, my main financial backer vanished with the funds we had been counting on, and I had to scramble to recover the start-up capital I needed. We managed to open the shop amid great uncertainty, but once it was open, we had full tables day after day. Our location was excellent. We were right in the middle of Hong Kong’s financial district, so we had a particularly large number of lunch customers. About a year later, a new financial backer appeared, and that cleared up our financial concerns.

In 2002, the hotel was slated to be demolished, so I established my own self-financed company: AHT International Limited. I reopened Japanese Restaurant Agehan, not as a joint operation but as my own enterprise, on the second floor of Hong Kong’s massive high-rise, Exchange Square—which was also the location of the Consulate General of Japan. I opened several more restaurants, until in 2009 I opened a kappo-style restaurant called Japanese Restaurant Yasuhan. Here, unlike my other restaurants, we take customers by reservation only, and there is no menu. Customers may bring their own beverages, but they leave the food up to us. It is a small shop with only 18 to 20 seats, intimate enough so that we can communicate with all our customers personally.

Japanese Cuisine in Hong Kong

In the mid-1970s when I first came to Hong Kong, there were only about 30 Japanese restaurants, and mostly Japanese were involved in these. The customers were primarily Japanese expatriates and wealthy local residents. Of the Hong Kong people who came to our shop, only about 20 or 30 percent would eat raw fish. At that time, we received Japanese ingredients from Tokyo: one shipment of ingredients every two months by sea and one air shipment per week. Kikkoman’s soy sauce and noodle dipping sauce were regulars in the sea shipments, while the air shipments included Japanese eggplant, Japanese cucumbers and daikon that we used for our nukazuke pickles (vegetables pickled in rice bran), along with Matsuzaka beef, fatty tuna (toro) and other fresh seafood. At that time, a single serving of sukiyaki would have cost nearly the same as one month’s salary for some people, and so Japanese cuisine was considered a luxury in those days.

Currently, there are some 1,300 to 1,400 Japanese restaurants in Hong Kong, ranging from the affordable to the exclusive. The majority are “Japanese-style” restaurants run by local people whose cooks trained here for several years in restaurants staffed by Japanese. I had a surprise experience in one of these restaurants, when miso soup was served instead of tea when I sat down at the table. On the other hand, these days the people of Hong Kong have more opportunities to enjoy the real thing if they have the chance to visit an authentic Japanese restaurant, or travel to Japan. This kind of exposure is turning their tastes toward more genuine Japanese cuisine. The number of Hong Kong people who order raw fish has been increasing. Salmon, hamachi (yellowtail), uni (sea urchin) and akagai (ark shell) are all quite popular now.

Championing Japan’s Food Culture

Rôtisseurs during the test to become a member

For many years, I’ve been engaged in activities to spread an appreciation for Japanese food culture. Since 1985, I have been a member of the Hong Kong Japanese Restaurant Association, which was founded in 1980. With them, I was involved in negotiations between the Hong Kong and Japanese governments over the issue of mercury levels in tuna, and in organizing Unagi Festivals during the 1980s and 1990s, where we offered unagi (eel) at Japanese restaurants to familiarize Hong Kong with the taste of unagi cuisine. Following the March 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, we launched a month-long event starting in May 2011 called “Love Japanese Food” to promote understanding about the safety of Japanese food products, and this involved 350 restaurants who organized various promotional campaigns.

Japanese Restaurants in Hong Kong

What I always try to do is to serve Japanese food that tastes no different from that served in Japan. We don’t modify the taste of our dishes to suit the local palate; we create only authentic Japanese cuisine. I hope Japanese restaurants in Hong Kong continue to improve their skills, especially in regard to flavor and fish-cooking techniques. What I want to do now, using my own experience, is to teach Japanese food culture to those who operate Japanese restaurants in Hong Kong, while continuing to support activities that promote an understanding of the safety of Japanese food products. My dream is to build a cooking school in Hong Kong, where chefs can learn authentic Japanese cuisine.

Photos courtesy of Ryuko Abe