The Sugar Road

This third installment of our current Feature series traces Japan’s historical trade routes by which various foods were originally conveyed around the country. This time we look at how sugar came to make its way throughout Japan

by Masami Ishii

From Medicine to Sweets

According to a record of goods brought to Japan from China by the scholar-priest Ganjin (Ch. Jianzhen; 688–763), founder of Toshodaiji Temple in Nara, cane sugar is thought to have been brought here in the eighth century. Sugar was considered exceedingly precious at that time, and until the thirteenth century it was used solely as an ingredient in the practice of traditional Chinese medicine.

In Japan, the primary sweeteners had been maltose syrup made from glutinous rice and malt, and a sweet boiled-down syrup called amazura made from a Japanese ivy root. But by the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century, sugar was being used as a food ingredient here: it is mentioned in a teikin orai (a textbook on wisdom for daily life) dating from that time that describes sato yokan, a jellied sweet made with red beans and sato (sugar). An illustrated scroll titled Shichiju ichiban shokunin uta-awase (“seventy-one poetry matches on 142 artisans”), dating from the late fifteenth to early sixteenth century, depicts sato manju, steamed buns filled with red beans and sugar. From these early examples, it seems that sugar had come to be used in making jellied sweets and steamed buns, and thus its varied uses gradually spread throughout society.

Sweets from the West

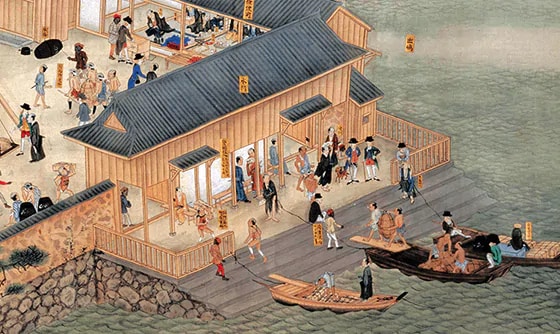

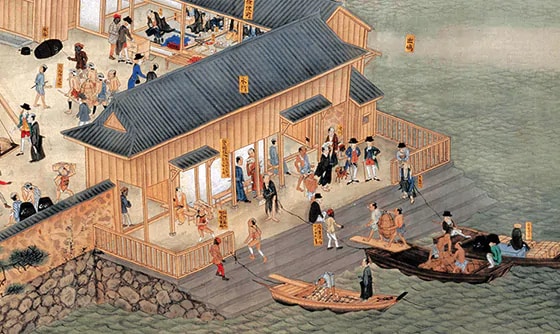

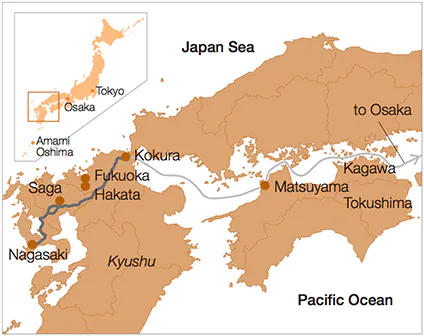

When missionaries from Portugal and Spain began coming to Japan in the late-sixteenth century, they introduced nanban-gashi sweets, including konpeito (Portuguese: confeito) and kasutera (castella sponge cake). When Nagasaki port opened to trade in 1571, some 100 kilograms or more of sugar began to be imported annually, and it was eventually disseminated throughout the towns of Hakata and Kokura in what is known today as Fukuoka prefecture in northern Kyushu island. As sugar made its way into various regions, different ways of using it evolved. Reflecting this history, in the 1980s the Nagasaki Kaido highway connecting the cities of Nagasaki and Kokura was dubbed “the Sugar Road.”

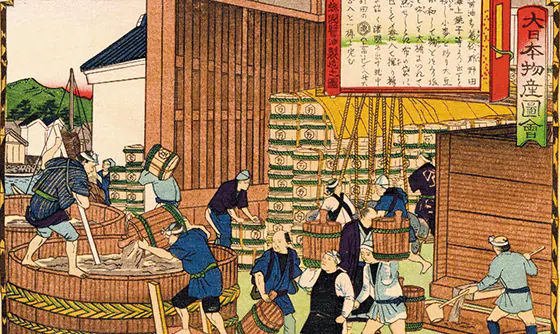

After Japan adopted its national seclusion laws in the early seventeenth century, cutting off trade and contact with much of the world, Nagasaki became the sole trading port through which sugar and other goods were imported from overseas. By the eighteenth century, the quantity of sugar imported on Dutch ships was between 500-1,000 tons annually—and this rose to over twice that amount, if we include sugar imported on Chinese ships. As a result of the increase in sugar imports, a special storehouse was built in Nagasaki from which sugar was shipped to wholesale warehouses in Osaka and then distributed around the country.

Along the Sugar Road

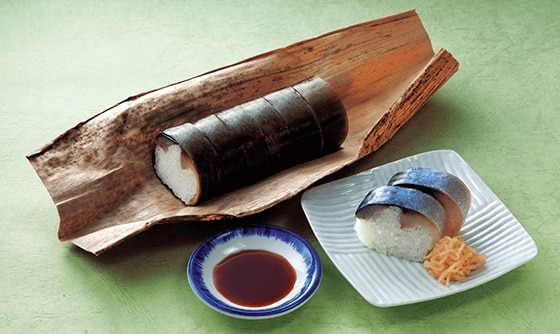

The culture of sugar in Japan continued to flourish in many ways. In Nagasaki, sugar was used to prepare dishes served in meals; however, sugar was better matched to making diverse sweets that were rooted in Western influences. Following along the sugar road, we find kasutera in Nagasaki, a baked cookie called maruboro in Saga, and a golden fios de ovos confection from Fukuoka known in Japanese as keiran somen that is made of threads of egg yolk cooked in sugar syrup. It is unsurprising that the founders of two of Japan’s leading makers of sweets were both born in this area.

The culture of sugar did not linger in northern Kyushu alone, but spread along the distribution routes to Osaka and Edo (now Tokyo). The confection known as taruto (Dutch: taart), for which the city of Matsuyama in Ehime prefecture on the island of Shikoku is famous, is in fact is a kind of moist sponge roll filled with sweet bean paste. This style of cake originated when the lord of the Matsuyama domain, in charge of guarding the city of Nagasaki, ordered his men to learn how to make Western-style sweets. Originally, the wrapped filling was jam, but bean paste was later substituted to reflect local tastes, as occurred in many cases following on the introduction of Western sweets.

Domestic Production

The production of sugar in Japan itself was long in coming. In the early seventeenth century, it is said that someone from Amami (today part of Kagoshima prefecture) brought back the method of making kurozato (an unrefined, dark brown sugar) after being shipwrecked in China. The manufacture of white sugar required advanced refining technology, but the eighth Tokugawa shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751) encouraged the cultivation of sugar cane, and by the end of the eighteenth century, domestically produced white sugar had widely circulated in the market. Most notably, in Shikoku’s Sanuki and Awa provinces (present-day Kagawa and Tokushima prefectures, respectively), refining techniques were advanced enough around the 1800s to produce the fine, white wasanbon sugar that is still prized today as an ingredient in high quality Japanese confectionery.

Meanwhile, great quantities of sugar appear to have circulated in Japan not only through the regular import markets, but also on the black markets. Domestic production, which started in the early eighteenth century, helped increase availability and this probably added impetus to its general consumption. In the late eighteenth century, sugar became so popular that ordinary people began to sprinkle it on foods such as cooked rice or udon noodles.

Today, Japan imports some 1.3 million tons of sugar annually. As these imports have increased through the years, sugar has slowly come to influence and redefine Japanese cuisine through its use as a day-to-day seasoning in ordinary cooking, as well as its appearance in an infinite variety of sweets—not only in Western-style pastries and cakes, but in contemporary and traditional Japanese confectionery.