The Development of “Clear” Sake

Sake, Japan’s traditional brewed alcoholic beverage, is made simply from rice, water and rice koji fermentation starter. In this second installment of our series on sake and its role in Japanese culture, we consider its origins and historical development.

Elements of Sake

Brewed alcohol made from rice has been produced since ancient times in Japan, but the drink that we know today as sake is not the same as it was centuries ago. These days, when people refer to “sake,” they mean the clear beverage known as seishu, considered to be the epitome of Japanese sake.

Seishu is brewed by adding koji mold (aspergillus oryzae) to steamed rice, resulting in a fermentation process that converts the rice starch to sugar. Moto yeast, also known as shubo, or “mother of sake,” is added to induce alcoholic fermentation of the sugar. This simultaneous, complex process is carefully controlled, and results in the brewing of a sweet, dry genshu or raw sake with a high alcoholic content, unique in the world. It is believed that koji mold came to be used in making sake in around the fourth century; moto yeast was added to the brew sometime in the sixteenth century, and from this point we can trace the origins of sake as we know it today.

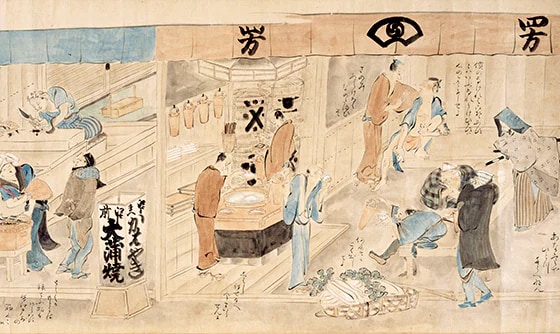

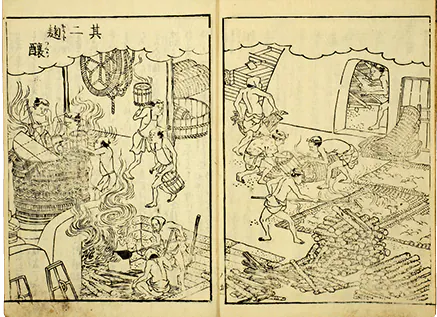

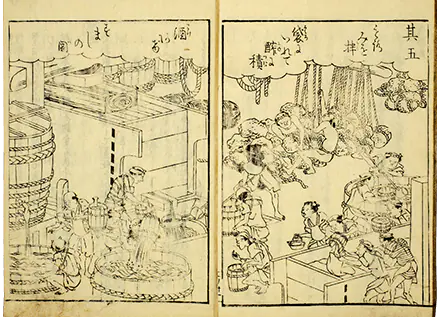

Illustrations depicting the sake-making process, from steaming the rice to the making of rice koji (upper) and sake-pressing (lower). From the book Nihon-sankai-meisan-zue (1830). Courtesy of Waseda University Library

Early Types of Sake

Prior to the eighth century, perhaps the most widely made rice wine was so-called overnight sake, or hitoyo-zake, made by allowing cooked rice or rice gruel to ferment naturally. One type of hitoyo-zake was reputedly known as kuchikami-sake, or “saliva sake.” A poem in the eighth-century Japanese poetry anthology Manyoshu suggests that, to make this sake, a maiden was responsible for chewing the cooked rice, which then became mixed with saliva; indeed, the enzyme amylase in saliva converts the starch in grain to sugar. Such a chewed-up mixture ferments, and results in mild alcoholization. This form of sake likely did exist in Japan, although it is unsubstantiated: a few ancient references to this process are found in Edo-period (1603-1867) records. Early modern mention of kuchikami-sake can be traced to Okinawa, and “saliva sake” is recorded as having been made as late as the early twentieth century in some Pacific islands.

Records suggest that hitoyo-zake developed into two other types of sake: ama-no-tamu sake and yashiori-no-sake. Ama-no-tamu sake is mentioned in the Nihon shoki (“Record of Japanese history”) dating from the year 720: if we interpret tamu as referring to “sweet taste” or “delicious,” we may infer that this was probably a sweet sake, similar to hitoyo-zake. It is difficult, however, to corroborate this either historically or by the science of fermention. Yashiori-no-sake is mentioned in both the Nihon shoki and the Kojiki (“Records of Ancient Matters,”) in 712. The term yashiori can be interpreted as meaning “eight times pressed,” which would suggest that it was quite a strong beverage. According to ancient Japanese myth, this was the drink used by the storm god Susanoo-no-mikoto to intoxicate and slay the Eight-Forked Serpent.

Sometime following on the development of hitoyo-zake, another sake called shitogi was made from rice flour, and there are indications that it may have been used in ritual offerings or during other special events. Shitogi was generally made by soaking white rice in water and then grinding it with a stone mill, which produces a slightly damp white flour. This flour, or shitogi, was dissolved in cold or hot water and was essentially a “rice juice,” but if left at room temperature for a time, various airborne yeasts triggered a natural fermentation process.

The Emergence of Modern Sake

During the Heian period (794-1185), the royal court in Kyoto established an office in charge of making sake for various rituals and observances. By the fifteenth century, sake-making had become quite prevalent, and several hundred small sake brewers had appeared in the city of Kyoto.

The manufacturing know-how which utilizes moto yeast had not yet been discovered, and so the sake during this time was probably nigori-zake, an unrefined or cloudy sake. The temple priests of Nara Prefecture eventually took the lead in so-called sake-making technology, and, through the use of koji mold and moto yeast, gradually developed methods for making sake of a stable quality. By the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries, techniques for brewing clarified sake—seishu—had become firmly established in a procedure that was nearly identical to contemporary sake production processes.

During the Edo period, sake brewers in the town of Nada in Hyogo Prefecture—still famous for its sake production even today—produced large amounts of high quality seishu to ship to Edo (now Tokyo). Seishu was first transported primarily by ship; later, spurred by the spread of Japan’s railway network in the Meiji period (1868–1912), sake breweries sprang up all over the country and began to distribute their products throughout Japan. Sake production was slow to develop in southern Kyushu and Okinawa, however, because the high humidity and warm climate were unsuitable for the fermenting processes and storage. These areas became better known for the development of shochu, a distilled spirit.

The essential method of utilizing koji mold and moto yeast to brew seishu clarified sake was well established by the eighteenth century, yet this fundamental process has been gradually improved upon throughout successive centuries. Contemporary sake carries with it the refinement of the brewers’ craft, founded in ancient tradition.