The Culture of Chanoyu

In our continuing exploration of the world of Japanese tea, this issue’s feature considers the art of chanoyu, the Japanese tea ceremony—a complex discipline that has inspired the philosophical and aesthetic spirit of Japan.

A phrase that originates from the culture of the chanoyu tea ceremony is ichigo ichie, which translates literally as, “a meeting that occurs once in a lifetime,” conveying the notion that each encounter is unique and special. When a host invites guests for a tea ceremony, they share the awareness that such an occasion is significant, and thus commit to and engage in the experience with utmost sincerity. The culture of chanoyu is not simply about the drinking of tea; it involves respect for others, courtesy and the spirit of hospitality.

Modern chanoyu culture dates back some 450 years to the latter half of the sixteenth century. Tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) elevated the practice to a sophisticated art, founded on the Japanese concepts of wabi and sabi—an appreciation for simplicity and serenity, wherein concentration on the act of preparing and drinking of tea in the tranquil space of the tea room grants calmness and introspection.

Many other tea masters, including disciples of Rikyu, continued to develop the culture of chanoyu, and thus formulated diverse styles, or “schools.” One of these instills an element of “elegant beauty,” called kirei sabi, into the wabi-sabi aesthetic. In the late eighteenth century, senchado using sencha infused tea leaves, rather than powdered matcha, were founded, with an emphasis on spiritual refinement and wisdom. Among the most famous tea schools today are those tracing their lineage to Rikyu, including the Omotesenke, Urasenke and Mushakojisenke schools. Others reflect their samurai origins, including the Enshu and Sekishu schools, while sencha practices include the Ogawa and Hoen schools. Each revolves around its own unique chanoyu utensils and procedures, which differ slightly from one school to the other; yet all share the same spirit of mutual respect, courtesy and hospitality.

Tea Ceremony

Courtesy of OMOTESENKE Fushin’an Foundation

Courtesy of Tea Museum, Shizuoka(left)

There are certain established elements involved in a tea ceremony. For a formal gathering, the host will invite several guests; the venue is typically a four-and-a-half mat (or smaller) tea room. On their approach to this room, guests walk along a simple path that passes through a small, well-tended Japanese-style garden. The entrance to the tea room is called nijiri-guchi, a small opening sixty centimeters square—just large enough for one person to stoop and pass through. Once inside, guests direct their attention to a recessed alcove called the tokonoma, where they may admire a hanging scroll and/or an arrangement of flowers.

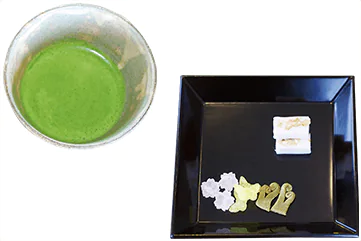

Next, to complement the tea ceremony, a special kaiseki ryori meal is served which features fresh seasonal fish and vegetables. Accompanied by sake, the meal basically comprises soup, a mukozuke side dish, a nimono simmered dish and a yakimono grilled dish. The food is delicately arranged in harmony with the ware upon which it is served, and laid out on individual trays called zen. To finish the meal, guests enjoy Japanese wagashi confectionery, which concludes the first half of the tea ceremony. After a brief interval, the guests reenter the tea room, where tea is then prepared by their host in accordance with a set of beautifully and precisely choreographed movements called temae. Two types of matcha are prepared: a thick version called koicha, followed by the lighter usucha. The formal tea ceremony ends here. More popular, simplified tea ceremonies may offer only usucha and wagashi; these are usually held in a large room where many guests can be accommodated.

Utensils of Tea Culture

A number of utensils are used in the tea ceremony. Some of these include the containers which hold the matcha—either a lacquered natsume, or a ceramic cha-ire; a cha-shaku tea scoop to measure out the matcha powder; a cha-sen bamboo whisk for mixing the tea; a kama iron pot for boiling water; and a tea bowl from which guests drink the prepared tea. To enhance the atmosphere, the host will have selected a special calligraphic or painted hanging scroll to place in the tokonoma, along with seasonal flowers arranged in a bamboo or ceramic container. There are many tea utensils still in use today which are historically and artistically significant, some of which are designated as National Treasures. The simple appreciation of seeing such priceless items is one of the pleasures of chanoyu.

Chanoyu Past and Future

Courtesy of Tea Museum, Shizuoka

The distinctive charm of chanoyu has evolved through the centuries in response to the relevant customs and routines of daily life. As an example, there is a style of tea ceremony devised some 150 years ago that involves performing temae while seated on a chair at a table. Chanoyu culture has been refined gradually throughout its long history: the original intent of merely drinking tea has expanded, as people indulged a desire to embellish this act with lovely utensils, or to create an exceptional tea room where host and guests might experience a truly intimate space. Throughout history, chanoyu can be said to have exerted a tremendous influence on the Japanese way of life as a whole, prompting advancement in the arts and crafts, inspiring talent and creativity in architectural and garden design, influencing the refinement of personal comportment and manners—even kindling transformations in Japanese cuisine.

In times like ours, when our values and ways of life are so diverse, and in the face of global conflict, surely the essence of chanoyu—which elevates respect for others in the spirit of hospitality while promoting feelings of peace—is needed more today than ever before.