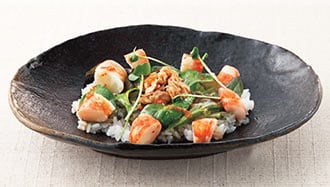

Foods Made with Rice

Our series about rice concludes with a look at some of the many delicious foods made using this traditional Japanese staple.

Rice is at the foundation of Japanese food culture, and it pervades Japanese cuisine in its many diverse processed forms, including fermented rice-based products, foods made from glutinous rice and those made using rice flour. Indeed, rice is such a fundamental element in the Japanese diet that the Japanese word for cooked rice, gohan, implies “meal” in general.

Fermented rice

Nihonshu, or sake, is made by adding koji fermentation starter to steamed rice, which converts the rice starch to glucose. When yeast is added to this sugar-rich rice mash, alcohol is produced. After fermentation is complete, a cloudy white liquid forms that is then strained to make seishu clear sake—an extract of the rice. The remaining sake-kasu lees are typically used to pickle vegetables, or as a marinade for fish and meat.

Rice vinegar, made by fermenting sake with acetic acid bacteria, was once considered a luxury product; during the Edo period (1603- 1867), less-expensive kasu-zu “lees vinegar” made from sake-kasu was introduced and became widely available. Sake is also distilled to make shochu liquor, which is common in Kyushu and Okinawa. Rice shochu, glutinous rice and rice koji are used to make a sweet sake called mirin, which was originally consumed as an alcoholic beverage; since the mid-eighteenth century, however, mirin has more often been used as an essential seasoning in cooking Japanese dishes.

Glutinous rice

The varieties of rice grown in Japan generally have a stickier texture than those grown in other parts of the world. Particularly so is mochi-gome Japanese glutinous rice, referred to as “sticky rice” after it has been steamed. Mochi is made by pounding freshly steamed sticky rice with a mortar and pestle while it is hot and can then be formed while still warm and soft. In eastern Japan, pounded mochi is generally flattened and cut into rectangular pieces, while in western Japan, it is more common to shape pounded mochi into flat round cakes. The mochi retains its shape as the rice cools, dries and hardens.

During the New Year, it is a national tradition to stack and decorate two round mochi cakes. Called kagami-mochi, these cakes are presented as offerings at household shrines. Kagami-mochi, together with salt and sake, have been used as offerings to the deities since antiquity. Mochi was once consumed more frequently, but nowadays it is mostly consumed on special occasions, such as during the New Year, other seasonal events, weddings and celebrations. The hardened mochi is softened by roasting or by gently boiling before eating. Dried mochi is an excellent preserved food that can be broken up into pieces for deep-frying or roasting seasoned with soy sauce or salt to make rice crackers called arare or kakimochi.

Rice flour and sweets

Raw rice is also ground into flour. Rice flour can be made from either non-glutinous or glutinous rice. A well-known example of the latter is coarse domyoji flour, made from steamed glutinous rice that has been dried and broken up. Different rice flours are used in making different types of wagashi Japanese confectionery. For example, kashiwa-mochi is made from non-glutinous rice flour and is enjoyed on Children’s Day on May 5. Sakura-mochi, sold around cherry blossom season, is made with domyoji flour in the western Kansai region. Daifuku-mochi, usually made of glutinous rice flour, is an accompaniment to tea, regardless of season or occasion.

How did people make sweets in the days before sugar was widely obtainable? Old records tell of making something called amazura by boiling down the sap of Japanese ivy. This syrup is mentioned in the Makura no Soshi (The Pillow Book), a collection of essays written one thousand years ago, which suggests that amazura was available only to those of high rank. What the general populace did to obtain sweetness is not known, but amazake, a sweet drink made by fermenting rice with rice koji, may have been one source. It is also thought that mizuame, a syrup made from rice, was savored. So rice was used as a source of sweetness as well.

The scope of using rice flour is expanding. Rice-flour bread has become especially popular here, with a wide variety of breads now sold at bakeries. Spurred by consumer demand, home bread-making machines that can be adjusted to produce 100 percent rice-flour bread are even available on the market. Rice flour’s gluten-free aspect is attractive, and it is used to make not only bread, but pasta and tempura flour as an alternative to wheat flour. Rice does contain protein, although not at such a high percentage as wheat: it has even been described as “the complete food,” because, for one thing, it has an excellent balance of twenty kinds of the amino acids that make up protein. Breads and other foods made with rice flour, therefore, are likely to attract more attention in the future from the viewpoint of nutritional value. Rice also contains about 1 percent fat, and is used to produce rice oil, which is considered healthy because it does not oxidize easily.

These diverse methods of processing rice are testimony to the enduring influence of rice in Japanese society and its traditions. Although actual rice consumption has been decreasing annually, it is anticipated that innovative new types of rice products will be developed, bringing about a new era in Japan’s rice-eating culture.