April 2017

Japanese Cuisine Around the World

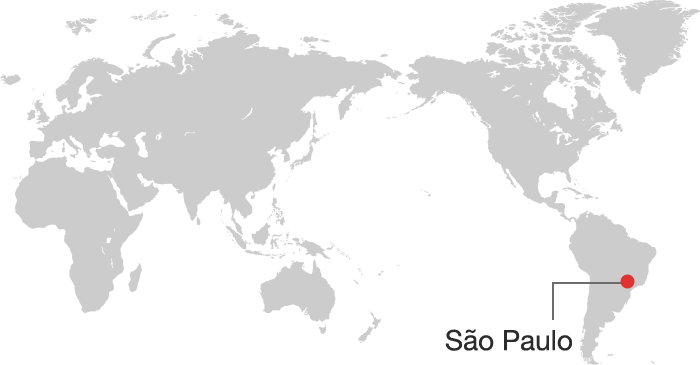

The annual Food Forum Special Report presents people who are introducing the pleasures of Japanese cuisine in countries around the world. This year we visit chef and restaurant owner Shinya Koike in São Paulo, Brazil.

Shinya Koike

Born 1957, Tokyo. Relocated to Brazil in 1994, where he founded five Japanese restaurants. Since 2007, Chef Koike has chaired the Japanese Food Promotion Committee of the Brazilian Society of Japanese Culture and Social Assistance. He actively promotes washoku through lectures and demonstrations, including during the Japanese Prime Minister’s visit in 2014. He helped establish Brazil’s first Sushi Chef Championship, certified by the Federation of Japan Sushi Industry Health Associations and the World Sushi Skills Institute. In 2016, Chef Koike received the Minister’s Award for Overseas Promotion of Japanese Food from the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Rua Jerônimo da Veiga, 74-Itaim Bibi, São Paulo, Brazil

Tel: +55 (11) 3078 3883

www.sakaguraa1.com.br

Av. das Américas, 8585-Vogue Square, Barra da Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Tel: +55 (21) 3030 9092

www.shinkoike.com.br

I first moved to Brazil in 1994 at the invitation of a friend who planned to open a Japanese restaurant in São Paulo, but eventually ended up working at a large-scale Japanese restaurant, followed by a stint as a sous-chef. In 2004, I opened my own place called Syutei A1. We had only 13 seats, menus were handwritten daily, and we served a variety of Japanese dishes including hijiki-no-nimono simmered hijiki sea vegetable, kinpira-gobo braised burdock root and carrot, grilled fish and tempura.

Japanese Traditions in Brazil

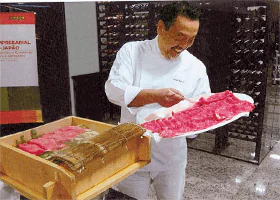

steaming technique at a Japan-Brazil

dinner reception.

To give some background, there were only a handful of Japanese restaurants in São Paulo in the early 1990s, and these targeted mostly Japanese expats and second-generation, or nikkei, Japanese-Brazilians. When Brazilian-operated Japanese restaurants first appeared around 1995 in upmarket São Paulo neighborhoods, this marked the beginning of the Japanese food boom, where all-you-can-eat Japanese and sales-by-weight restaurants were hugely popular.

So when I opened Syutei A1, conditions for any restaurant serving authentic Japanese cuisine were very favorable. The population, particularly in São Paulo, includes many nikkei interested in Japan, its traditions— and its cuisine. There is a huge consumer segment that knows and loves Japanese food. Furthermore, thanks to the enormous efforts of immigrant farmers from Japan who established themselves in Brazil in the early twentieth century, there are suburban farms providing a plentiful supply of the Japanese vegetables needed in Japanese cuisine, such as cucumber, eggplant, daikon, yam, yuzu citrus and ginkgo nuts. I am quite sure there is no other country outside Japan where such abundant, high quality produce can be obtained so easily. Because of these particular circumstances, Syutei A1 was blessed from the beginning. Its success led to my opening the 46-seat Restaurant Aizomê in 2007, which serves a kaiseki menu that changes daily. In 2008 and 2009, Aizomê was named best Japanese restaurant in São Paulo.

Authentic Flavors

with sliced yam and flavored shiso.

The Brazilian economy stabilized over the past decade, and it became easier to obtain ingredients from Japan; by the early 2000s, we could source kombu, katsuobushi (dried bonito), instant foods and seasonings. Pre-prepared seafood products and gourmet items appeared on the market, and kurage jellyfish, iidako octopus, shark fin and shirauo icefish were served as sushi in high quality shops and were popular with Brazilian consumers. When I first arrived in Brazil, a few small shops sold Asian and Japanese foods and ingredients; but by 2000, there were supermarkets selling mainly Japanese foods. The rush from 2000-2012 to open new Japanese restaurants increased the number of Japanese-food fans. At the same time, refrigerated container shipments of Japanese sake started to arrive here, and the availability of imported unpasteurized sake triggered a boom; the sake market took off and sake sommeliers thrived. Consumers slowly shifted from locally made seasonings and sake to genuine Japan-made products and so, reflecting their demand for higher quality taste, the authenticity of Japanese restaurants improved.

sushi and tempura.

As the clientele of São Paulo’s restaurant market gradually matured, in 2012, I opened the 130-seat restaurant Sakagura A1, a more extensive version of my original shops. Its concept is to provide a spectrum of washoku for a broader clientele of all ages, including Japanese, nikkei and non-Japanese-Brazilians. Our menu concept focuses on flavors created with genuine Japanese seasonings: Brazilian soy sauce is sweet, and simmered fish, for example, can be made only with true Japanese soy sauce. Our local staff also follow traditional Japanese preparation methods, like making dashi using kombu and bonito. It is my goal to change the false Brazilian conception that Japanese food is just sushi and sashimi. I hope to familiarize them with the true depth and variety of this cuisine. I believe that by enhancing our diners’ experience through fine Japanese food, we spread greater understanding of washoku traditional Japanese cuisine here in Brazil.

Sharing Washoku

The environment for washoku here continues to be favorable, and awareness continues to grow. Today there are an estimated 700-800 Japanese restaurants in this city, and this trend is spreading to other parts of the country, generating more demand for quality ingredients, techniques and information about Japan and its culture. My longtime plans to expand to Rio de Janeiro were realized last year when I opened Restaurant SHIN KOIKE and Izakaya ROMAN. The two share the same kitchen and combine washoku dining and bar in a completely new style, unprecedented in Rio. I designed this establishment to function as a center for my washoku education and training activities in that city.

garnish at Sakagura A1

I continue to pursue direct, person-to-person exchange about food-related matters like ingredients, cooking tools and tableware. I am eager to see the number of washoku fans grow as a result of increased opportunities to enjoy the authentic cuisine. I want to do all I can to transmit the proper information and skills to food industry professionals to ensure that safe, reliable Japanese food is served. Today, washoku is still considered a “foreign culture” in Brazil, but I hope to see this food culture take firm root here. I believe that authentic culture truly endures, so I will continue my endeavors to pass on and share the enjoyment of washoku.

Photos courtesy of Shinya Koike