January 2013

Japanese Cuisine Around the World

Food Forum is pleased to present this special report by Akira Oshima, former Honorary Executive Chef of two ground-breaking restaurants, Yamazato and Sazanka, both located in the Hotel Okura in Amsterdam. Here, Mr. Oshima recounts his pioneering experiences and success in introducing Japanese cuisine to the Netherlands over 30 years ago.

Akira Oshima

Born 1943 in Tokyo. In 1962, Mr. Oshima began his career at the Hotel Okura Tokyo. After training at famous traditional Japanese restaurants Tsuruya and Shinkiraku, in 1971 Oshima was named sous chef of Yamazato restaurant at the Hotel Okura Amsterdam; from 1977 he held the position of Executive Chef at both Yamazato and Sazanka. In 2002, he received a coveted Michelin star for Yamazato. In 2006, he was awarded the Ridder Orde van Oranje Nassau (knighthood) from the Dutch Royal House. From 2010 to 2012, he served as Advisor & Honorary Executive Chef of both Japanese restaurants at the Hotel Okura Amsterdam. In 2012, he received the Minister’s Award for Overseas Promotion of Japanese Food from the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries for his achievements in promoting Japanese culture through Japanese cuisine.

Yamazato (left), Teppanyaki Restaurant Sazanka (right)

Ferdinand Bolstraat 333, 1072 LH, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Tel: +31 (0)20 678 7111

www.yamazato.nl/en

www.sazanka.nl/en/Home.html

Until the late 1960s in Europe, although several Japanese restaurants operated in London and Paris, none served authentic Japanese cuisine. Prior to the opening of the Hotel Okura in Amsterdam in 1971, there were no Japanese restaurants in Amsterdam. The hotel’s Japanese restaurant, Yamazato, began from scratch. At that time, the Dutch rarely ate out and had little or no interest in Japanese cuisine. When I started at Yamazato, I figured we would need at least 10 years for the Dutch people to familiarize themselves with our cuisine.

The Dutch Meet Japanese Cuisine

When Yamazato opened in Amsterdam in the early seventies, the sashimi and sushi in particular were very poorly received. Of course fish is eaten in the Netherlands, but the Dutch were more familiar with herring, cod and sole. There was no custom of eating raw tuna, for example. The only dishes the Dutch really felt comfortable with were foods such as yakitori, tempura and sukiyaki—and even sukiyaki met with some resistance: the use of raw eggs put people off. Gradually, though, our teppanyaki restaurant saw increased visits by Dutch families.

In introducing Japanese cuisine, I believe it is essential to use Japanese terms for food and ingredients, and so from the start I told our staff to refer to our ingredients and cuisine only by their Japanese names. For instance, daikon should be referred to as “daikon,” not white radish. My reasoning was that “radish” already existed in the Netherlands—and we had to distinguish between them, otherwise people would get confused. So we used the Japanese names: sukiyaki was called sukiyaki, tempura was tempura, and so on. Today, these Japanese names are commonly used and understood throughout Europe.

Authenticity in Amsterdam

grilled red mullet rolls marinated in miso

My policy from the start was to serve authentic Japanese cuisine in the Netherlands. It’s completely misleading and unimaginative to say that one cannot serve authentic Japanese cuisine outside of Japan. We can recreate Japanese flavors with local Dutch ingredients by using seasonings such as soy sauce and miso. If we were to use specially imported Japanese ingredients, then the Dutch couldn’t recreate these flavors for themselves. So I always tried to use Dutch ingredients; for example, I made nitsuke (fish simmered in soy sauce-based sauce) with sole that could be sourced in the Netherlands, and I included local squid when serving sashimi.

In the beginning, maguro (tuna) was unobtainable in the Netherlands, so I had to fly it in from Spain. At first, the airline refused to transport it, saying the cargo hold would smell of fish. But we negotiated and they finally agreed to fly the tuna to Amsterdam. It was a great experience, and nowadays tuna is flown in regularly.

The Element of Expertise

At first, only experienced Japanese chefs worked at Yamazato. But from around 1975, I thought that we needed to provide solid basic culinary training to young Japanese cuisine chefs to popularize kaiseki cuisine* in Europe. So I negotiated with some culinary schools in Tokyo to hire new graduates to work at Yamazato for three-year terms. I wanted them to understand that they could create authentic Japanese cuisine outside of Japan. Although we serve to the Dutch, we make dishes that Japanese would regard as authentic. My hope was that the young chefs who learned at Yamazato might move on to different places throughout the world and introduce authentic Japanese cuisine to those in other countries.

Seasonal Essentials

and its recipes.

At Yamazato, we changed our kaiseki menus on a monthly basis. Japan enjoys a variety of meat, fish and seasonal vegetables, but geographically speaking, the Netherlands is located farther to the north and it’s more difficult to source local ingredients that represent the four seasons. I tried to use them as much as possible: for example, June is the season for white asparagus and herring, November for chestnuts.

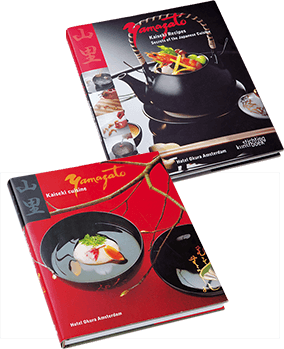

In 2002, Yamazato received a Michelin star, and although kaiseki had become better known by that time, all the books about kaiseki that were sold in Europe were English translations of Japanese books. I thought there should be a book about kaiseki in the local language, written by a chef. So, together with a photographer, we took photos of actual dishes that were served daily at Yamazato. I wrote the Japanese text and Professor Katarzyna Cwiertka of Leiden University translated it into both Dutch and English. My second book is a kaiseki recipe book.

Japanese World Cuisine

In 2009, a kitchen called the Taste of Okura was established in the shopping arcade of the hotel, which offeres classes on making sushi, kaiseki cuisine, teppanyaki and French cuisine; I taught sushi and kaiseki.

As for Japanese cuisine, the new Japanese fusion that began to emerge in the mid-1990s, as exemplified by restaurants Nobu, Zuma and Roka, has spread around the world. These new dishes have gone far beyond the borders of narrowly defined Japanese cuisine, and while overturning the old-school convictions (“Authentic Japanese cuisine must be prepared by an authentic Japanese chef!”), fusion dishes are emerging in French cuisine as well. In Europe today, Japanese cuisine is best known through Japanese fusion, sushi and teppanyaki.

I think that the emergence of Japanese fusion is a good thing, since it familiarizes people with Japanese food. However, amidst the fusion cuisine and the traditional favorites like yakitori, sukiyaki, sushi and tempura, I do want people to know about kaiseki. I want people to know what authentic Japanese cuisine really is, and that when they go to Yamazato, they can be assured that they will experience it.

Yamazato is committed to improving its cuisine and services so that diners in the Netherlands can enjoy kaiseki at its absolute best. My personal experience in introducing kaiseki cuisine to the Netherlands was invaluable, and I hope that I may continue to help promote Japanese culture through Japanese cuisine.

* Traditional kaiseki is Japan’s multi-course haute cuisine, whose varied and elegantly prepared dishes are served in a highly refined manner in a specific sequential order.

Photos courtesy of Akira Oshima