One-Plate Rice Dishes

Our current Feature series examines the fusion of Japanese and Western cuisines—referred to in Japan’s food culture as wayo setchu. In this second installment, we look at a distinctive type of fusion fare: dishes served together with rice on a single plate, with a focus on ever-popular curry rice and hayashi raisu.

by Yo Maenobo

First Tastes from the West

For a little over two centuries, from 1639 to 1854, Japan isolated itself from the rest of the world, only keeping open a window in Nagasaki for commercial relations with the Netherlands and China. While there were Japanese who had the opportunity to sample the exotic tastes of Western cuisine there at that time, they were probably very few.

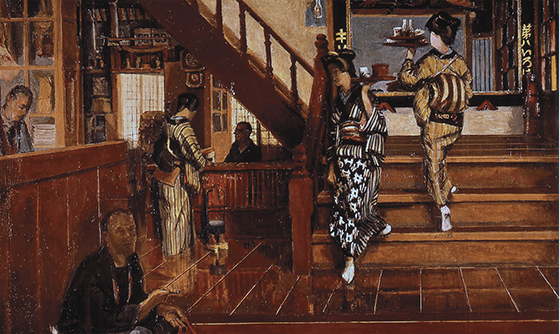

It is reasonable to assume that Western-style cuisine was truly introduced much later in Japan, when restaurants opened in treaty ports such as Hakodate, Nagasaki and Yokohama during the 1860s. The first Western-style restaurant in Edo (present-day Tokyo) was established just before the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

The customers of those early establishments soon found that the volume of food served was excessive for the Japanese appetite. Japanese at that time thought that things should be done properly, as in the West, and thus menus offered only full-course meals—considered the “authentic” style of Western dining. Most of these menus featured just three choices: low-, mid- and high-priced set meals. One rare exception was a famous sweets shop in Tokyo’s Ginza district, which earned a reputation for serving à la carte Western-style dishes in their restaurant, under the term sho-shoku (small-quantity dishes).

Cookbook Recipes in Demand

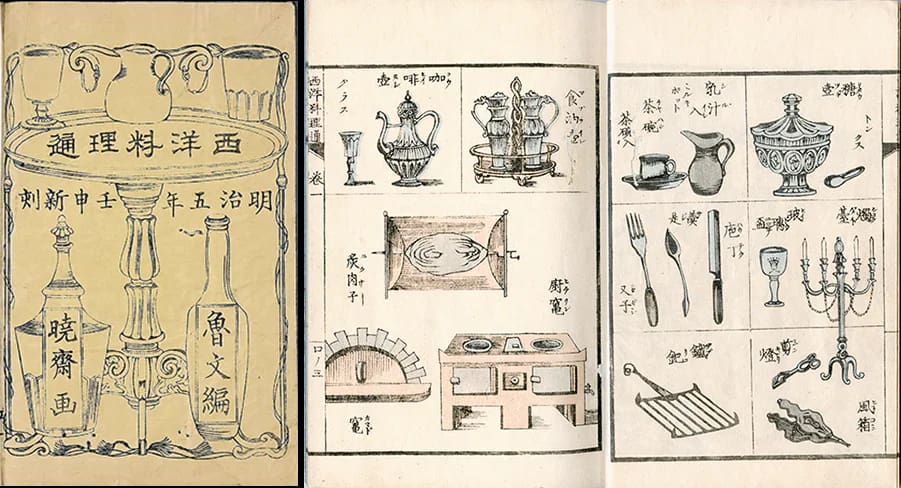

Compared to these authentic-style restaurants, cookbooks were a more practical means of making Western food easily accessible to the general public. After the emperor himself took the lead in eating beef, the trend of the times followed suit, which led to the publishing of Western-style cookbooks in Japan.

Among the earliest of these was Seiyo Ryori-tsu (“Connoisseur of Western-style cooking”), compiled by Kanagaki Robun in 1872, the author of the literary work Agura-nabe (“Cross-legged at the beef pot”), mentioned in the first article in this series. During the following forty years, Western cookbooks were among the more than 100 cookbooks published in Japan—a clear indication of how the consumption of meat and other Western dishes was welcomed in the country.

Early Western-style restaurants may have limited diners to the menu of the day, but by referring to cookbooks, those interested in Western foods could find a wider, more practical selection of dishes, and could follow their own tastes. Most cookbooks of this era were based on English-style recipes such as those found in Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861) by Isabella Mary Beeton, and in American cookbooks such as The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book. There was very little influence of French and German cooking.

Rice and Meat

At that time, most Western cookbooks invariably included a recipe for “curry and rice”—and it is this dish that has become a classic example of Japanese and Western fusion cuisine. Despite its Indian origins, curry and rice was introduced via England, where it had entered the diet from the British colonies; it was often made with white meat, such as chicken or rabbit. In Japan, its roots in India were not known, and curry rice here was served just as described in Mrs. Beeton’s recipe, with curried beef surrounded by a border of cooked rice.

This style of serving curry and rice did not become the norm, however. Two methods became more common in Japan: either serving the curry sauce partially or completely poured over the rice, or separately in a gravy boat, which was considered more refined. Both styles, however, were invariably eaten with a spoon in Japan, perceived at that time in England as a utensil intended for children.

Similar to curry and rice, another favorite fusion dish emerged: hayashi raisu. The name was probably derived from “hashed-meat rice,” owing to the similarity in sound. In England, it was common to consume leftover meat as “hashed meat”—meat that was diced and sautéed with onions and flour, combined with stock, then seasoned with salt and pepper. This was served on a plate together with boiled potatoes or slices of toast. In Japan, this concoction was intended, like curry, to be eaten with rice using a spoon.

Hayashi raisu made with beef and onions well sautéed in butter became extremely popular among Japanese at this time, and was referred to as irini—meaning a dish sautéed in oil and then simmered. In cookbooks published in Japan around 1910, beef, veal, lamb and chicken were all called for in hayashi raisu. In the 1920s, a pre-prepared roux for hayashi raisu was advertised for preparing six different types of yoshoku (Japanese-style Western dishes) most of which called for beef, which suggests that the evolution of “hashed-meat with rice” to “hashed-beef with rice” occurred around this time.