Courtesy of Yokohama City Central Library

Notable Nineteenth-Century Banquets

In our new series for 2020, Food Forum takes an in-depth look at the distinctive foods served at celebratory and ceremonial occasions, and the manner in which they are presented. In this first installment, we introduce a few of Japan’s more memorable historical banquets.

by Ayako Ehara

The word for festive dishes intended for entertaining guests is gochiso, the root meaning of which comes from “running about”—as in gathering ingredients, making elaborate preparations and so on—and refers particularly to luxury or gourmet dishes that require extra effort to prepare. The way in which such foods are served varies widely. By way of background to contemporary styles, here we describe three significant formal banquets held in the nineteenth century.

Entertaining Korean Envoys

In the period between 1607 to 1811, the Joseon (Choson) court of Korea sent a total of twelve delegations to Japan, mostly on occasions when the seat of the Tokugawa shogun changed hands. Receiving these delegations, each of which comprised some four hundred envoys, was the responsibility of the shogunate, and the entertainments and their scale evolved over the years. The banquet held for the highest-ranking members of the 1811 entourage was to be the last in the long history of Edo-period (1603–1867) Korea-Japan relations. In that year, to save costs, the banquet was held not in Edo (present-day Tokyo), but on the island of Tsushima, off the coast of Kyushu between Korea and Japan.

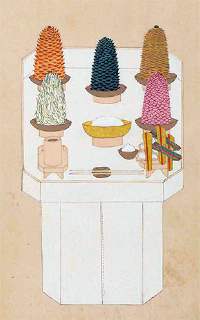

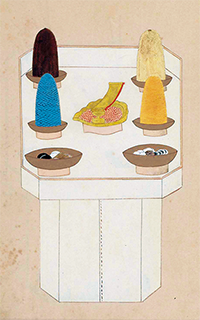

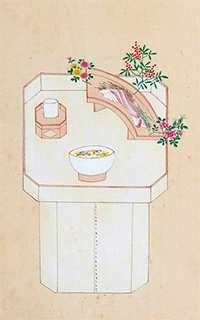

In those days, most banquets like this one were presented honzen style, wherein dishes were placed on low tray-tables called zen, which were served all at once. The highest-class menu of honzen was called shichi-go-san zen; literally, seven-five-three dishes on a zen. The dishes on the first three zen tray-tables were ceremonial and not intended to be eaten: the first zen was the main tray-table, called the honzen, and it held rice and seven dishes with dried fish, kamaboko fish cake and pickled vegetables (konomono); the second zen held soups and five dishes of dried foods, including dried seafood such as shark and squid. The third zen featured soups and three dishes, including Ise-ebi Japanese spiny lobster.

The fourth and fifth zen were actually consumed. These included sashimi, a steamed dish, Ise-ebi, sea bream marinated in miso and grilled, and other dishes. After the fourth and fifth zen, soup and diverse decorative or technically elaborate tidbits were served with sake. Wrapping up the honzen-style banquet were sweets and tea. Various constraints were typically imposed on the first three ceremonial dishes because of the custom of not consuming the meat of livestock; but in consideration of the dietary habits of the Korean envoys, boar and venison were included with the fourth and fifth zen in several banquets held for them over the years.

Shichi-go-san zen banquet for Korean delegation,1811. Detail from the illustration Chosenjin gokyouou shichi-go-san zen bu zu.

Courtesy of Hosa Library, City of Nagoya

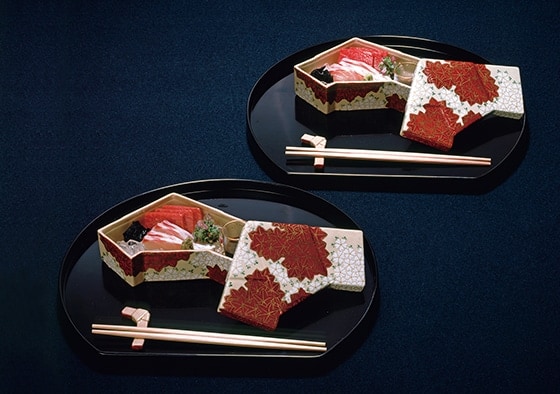

Banquet for Commodore Perry

In 1853 Commodore Matthew C. Perry and his ships landed in Japan, requesting that the country open to trade; one year later, he returned for the shogun’s response. In 1854, a banquet was held in Yokohama to entertain Perry and his party. It opened with sake served in traditional sake cups (sakazuki) along with several complementary soups, including miso soup and clear soup (both regarded as excellent accompaniments to sake); other refreshments included dried squid, young yellowtail, flounder, chikuwa and kamaboko fish cakes set out on deep square lacquered trays, called suzuributa. Numerous other dishes followed, mainly fish and fowl such as sashimi, Japanese tiger prawn, sea bream and duck. Woodblock prints portraying this occasion depict large platters and bowls in the center of the table laden with food which must have been shared by the diners.

These drinks and appetizers were then followed by the main meal. Two zen tray-tables were set before each person: the honzen held rice, soup, vinegared dishes made with abalone and other ingredients, a simmered dish of tofu and other ingredients, and pickles; the second zen held soup and a dish containing prawn and squid, accompanied by a smaller tray of grilled sea bream. In his journal, Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, Perry noted that the zen trays were placed on top of regular tables, allowing guests to eat while seated on stools. This thoughtful gesture was made by the hosts, who apparently understood their Western guests could not be expected to dine seated on tatami mats. Castella cake prepared as dessert for the meal was sent to the ships for later consumption.

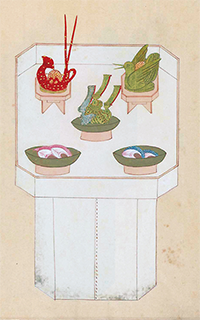

Dining in a Merchant House

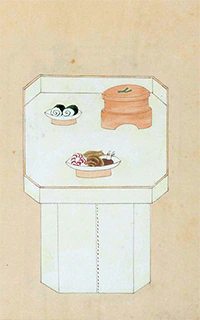

Courtesy of Tanaka Honke Museum

The Tanaka family of Suzaka city in Nagano Prefecture were wealthy merchants engaged mainly in the tobacco and sake-brewing business, and were purveyors to the Suzaka domain during the Edo period. The family often entertained eminent guests; one such event was a farewell banquet held in February 1851 for Koemon Ishida, a teacher who had been invited to educate and advise domain retainers.

After greeting guests with high quality sencha green tea and yaki-manju (small round buns filled with azuki red bean paste), sake and appetizers were served, including miso soup with monkfish (anko) spiced with sansho Japanese mountain pepper. These were succeeded by a suzuributa tray which held an array of delicacies, including simmered lotus root with sesame dressing, simmered shark meat, tamago-yaki rolled egg and boiled shrimp. A large bowl called an oohira was filled with simmered pheasant, grilled tofu, spinach and other ingredients; this was followed by a vinegared squid dish, clear soup with duck meat, and sashimi. The appetizers served on suzuributa and oohira were shared among diners, after which the main meal of rice, soup, a simmered dish and grilled salmon was presented on individual zen. Dessert was shiruko—azuki red beans simmered with sugar into a thick, luscious soup—with small mochi rice cakes. This grand banquet began before noon and continued until late at night.

Transitions in Style

In the case of the earlier Korean banquet, the menu started off with the main dishes, or staples, after which came sake and tidbits. In those later banquets held for Commodore Perry and Koemon Ishida, sake and appetizers were served first and shared by the guests; the staples of rice, soup and side dishes came afterward.

During the late Edo period, kaiseki-style meals began to appear in restaurants, wherein diners were first served sake and appetizers, and then the main meal, whose dishes were all served separately, one after another in a specific order, to each individual—similar to today’s kaiseki style. Different banquet styles which emerged over the years helped shape the banquet styles we know today.

Ayako Ehara was born in 1943 in Shimane Prefecture, and graduated from Ochanomizu University. She holds a Ph.D. in Education and taught for many years at Tokyo Kasei Gakuin University, where she is currently professor emerita. A specialist in food culture, the history of food education and cookery science, Dr. Ehara is the author and editor of many publications, including Katei Ryori no Kindai (“Modern Home Cooking”; 2012); Oishii Edo Gohan (“Delicious Edo-period meals”; co-author, 2011); and Nihon Shokumotsushi (“History of Japanese foods”; co-author, 2009).