Festive Food in the Home

Our current series is focusing on the distinctive foods served on festive occasions and for special events. This second installment introduces a few notable dishes served in the home during the Christmas and New Year’s holidays.

by Ayako Ehara

It was in 2013 that UNESCO declared “Washoku, traditional dietary cultures of the Japanese, notably for the celebration of New Year,” as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. In fact, among Japan’s traditional events and ceremonial occasions, the New Year holidays, called Shogatsu, are the most widely celebrated in Japanese households. A nationwide survey conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in 2015 found that around 88 percent of households serve traditional foods associated with the New Year, either every year or most years.

That same survey revealed that 73 percent of respondents reported that they also serve a Christmas feast. This custom was adopted through the influence of Western culture, and has now become more common in some homes than are certain Japanese traditional practices. Christmas festivities are often observed among those households with children, more than 80 percent of which dine on dishes related to this holiday. Here we introduce foods eaten during the Christmas and New Year’s holidays, and take a look at their respective backgrounds.

Christmas at Home

In December 1885, Christmas decorations made an early appearance in Yokohama, Japan, when a ship chandler, inspired by his world travels, trimmed his business storefront for promotional purposes. These days, Christmas trees and lights are a common sight throughout Japan. Christmas feasting revolves around “Christmas cake,” described in a 1907 Japanese culinary dictionary as a sponge cake with a sweet icing. The book also explains how to prepare a roast turkey for Christmas. In the 1910s, home-cooking and women’s magazines appeared, and December issues featured recipes for homemade Christmas feasts that included sponge cake with buttercream or whipped-cream frosting. This eventually became the standard for today’s Christmas cake; turkey, however, failed to win acceptance. Instead, roast chicken and other chicken dishes became the centerpiece of the Christmas feast. The style of Christmas dinner we take pleasure in today has been enjoyed in Japanese homes since the 1960s.

Today, pre-prepared roast chicken fills supermarket shelves at Christmastime, and a growing number of people order Christmas cake at cake shops or online. Cake choices are diverse: aside from the classic round sponge cake with whipped-cream frosting and strawberries, other temptations include Bûche de Noël (French yule log cake), German stollen and Italian panettone. Online videos offer instruction on preparing cakes from scratch, which some parents make with their children. It is children, after all, for whom Christmas is a particularly fun and eagerly anticipated occasion.

New Year’s Traditional Dishes

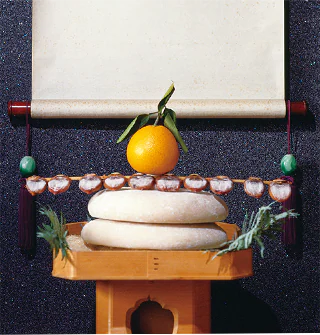

Immediately following Christmas, Japanese traditions define the menu. Shogatsu is the time when the deity of the New Year is welcomed into the home. Festive foods are made as offerings to the deity, and partaking of them is thought to ensure good health. In most households, the main offering is kagami-mochi, a pair of stacked round mochi rice cakes, one small and one large, with a daidai bitter orange and ten dried, skewered persimmons placed on top. (The word daidai sounds similar to the phrase, “to continue for generations,” and persimmons symbolize an abundant harvest.) In the past, each household made its own kagami-mochi, but these days they are usually store-bought.

Courtesy of HAGA LIBRARY

Traditionally, the New Year holiday is also a time for drinking toso, sake infused with medicinal herbs. Family members take turns drinking the beverage to protect against misfortune and illness, though nowadays fewer households include toso in their festivities. According to a 2017 survey conducted by the Washoku Association of Japan, over 80 percent of households serve New Year’s zoni, a soup containing mochi that is regarded as the most important of New Year dishes. Zoni differs by region, from shapes of the mochi to variations in soup and ingredients.

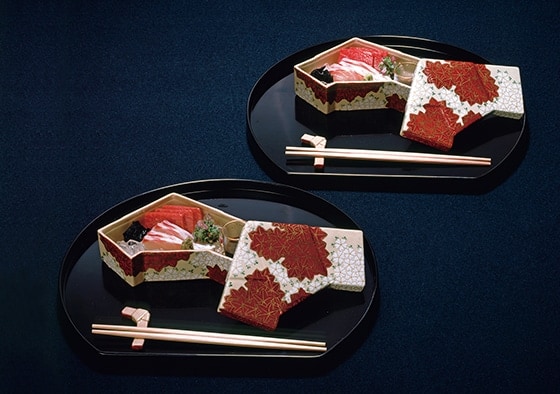

More than 80 percent of households also eat osechi ryori, an assortment of dishes which symbolize prayers for happiness and good fortune in the New Year. Served during the first three days of the New Year, these festive foods are beautifully arranged in a jubako—a lidded lacquer box comprising two or three stacked tiers. The custom of serving osechi ryori in jubako was introduced in schools and in women’s magazines around the year 1900, and first became widespread mainly in urban areas. There are many osechi ryori, but three in particular are eaten in over 80 percent of households: kazunoko, herring roe marinated in soy sauce-based dashi; kuromame black soybeans in syrup; and tazukuri, small sardines in a crisp glaze of seasoned soy sauce, mirin and sugar. Along with zoni, these dishes have a long history of being served not only as part of the New Year’s meal, but also as tidbits at various ceremonies and rituals.

Other common traditional osechi ryori include kamaboko fish cake; egg dishes; kinton (sweet potato paste with chestnuts); simmered chicken and root vegetables; and namasu (julienned daikon and carrot in sweetened vinegar). Meats such as braised pork belly, roast beef or various types of ham are included. More households prepare homemade dishes during the New Year than on any other festive occasion, but even so, with the exception of zoni, simmered dishes and namasu, a growing number order ready-made osechi ryori, prepared by professional outlets such as restaurants and department stores.

Although the origins of these two celebrations differ, both Western-style Christmas festivities and the traditional Japanese New Year’s holidays are two auspicious events on the Japanese calendar, and both are defined by warm family gatherings and special feasts.