Courtesy of Kamigamo Jinja

Food Fit for the Divine

As Food Forum concludes its series on the special foods of Japan, this final installment explores the significant foods presented at jinja (Shinto shrines) and Buddhist temples, which underpin religious beliefs.

by Ayako Ehara

Japanese religious beliefs are characterized by a duality of Shinto and Buddhist traditions. Until the recent past, the typical home in Japan had two altars—a Shinto kamidana and a Buddhist butsudan—and today, many still do. Daily prayers are accompanied by placing water and cooked rice on both the kamidana and butsudan. This feature introduces the food and offerings at jinja and temples, which have supported people’s religious beliefs.

Shinsen Offerings

Japanese have long believed that everything of nature—mountains, trees, animals—is endowed with a divine spirit, or kami, and that all life is sustained by such deities. People presented special foods as offerings, called shinsen, to certain deities, and after such rituals were performed, it was believed that by sharing and consuming these offerings, divine protection would be granted.

The rituals and ceremonies calling upon safety from natural disasters, or to ask for an abundant harvest or fish catch, are called matsuri, which always begin with shinsen offerings to the kami. In early times, prepared foods were usually presented, which is still the case at some jinja; but since the Meiji era (1868-1912), it has become more common to offer raw and dried foods.

Courtesy of Ise Jingu

Courtesy of Ise Jingu

At Japan’s sacred Ise Jingu, twice-daily offerings in the form of meals have been made to the kami in the morning and evening for some 1,500 years. Over one thousand matsuri are held at this jinja each year, but the most significant of these is the Kanname-sai annual harvest ritual in autumn. The Kanname-sai shinsen comprise some thirty small dishes whose basic elements include steamed rice, water and salt, accompanied by sake and foods that represent the sea, rivers, mountains and fields. Among these are noshi awabi dried abalone strips, considered an essential offering at Ise Jingu since ancient times.

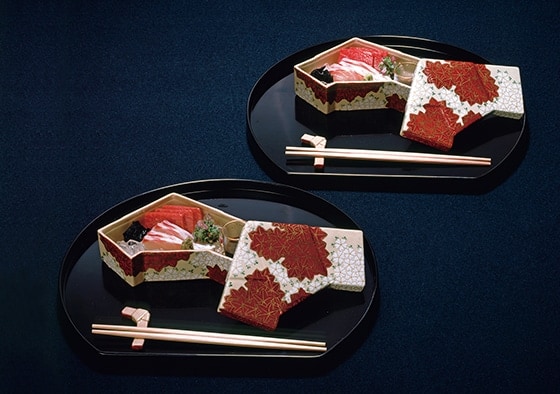

Courtesy of Kamigamo Jinja

Quite elaborate shinsen are prepared for Kyoto’s Aoi-Matsuri ritual (once known as Kamo-sai; aoi refers to a species of wild ginger), an early summer tradition that takes place at both Kamigamo and Shimogamo Jinja. At Kamigamo, shinsen offered within the honden main sanctuary include steamed rice, mochi rice cakes, carp, fowl and salted sea bream, accompanied by chopsticks. Outside the honden doors, further offerings involve over thirty different small dishes, each piled high with foods such as steamed rice, salt, sake, fish and fowl (see top photo). In a garden facing the honden, deities originating from other regions are presented with shinsen of dried salmon, dried squid, wakame seaweed, aonori seaweed and salt, all in a vermillion lacquer box (see photo below).

Shinsen throughout Japan vary by season and locale, featuring distinctive ingredients and prepared dishes. Though they have evolved through the centuries, they represent the essential elements that define Japan’s food culture.

Courtesy of Kamigamo Jinja

Shojin-ryori Temple Food

Vegetarian temple cuisine, called shojin-ryori, existed in Japan during the eighth century, and was further developed here by priests who had traveled to China in the late twelfth century to study Zen Buddhism. Among them was the Zen master Dogen (1200-1253), who was active in spreading the practice of zazen seated meditation as well as disseminating the fundamentals of shojin-ryori. Shojin means to pursue training in Buddhist teachings; shojin cuisine emphasizes the use of ingredients in their entirety, wasting nothing and—in accordance with the Buddhist injunction against the taking of life—uses no meat, only vegetables.

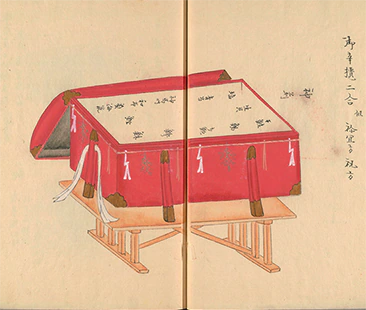

Dogen regarded the preparation and consumption of meals as a form of religious training, and for those priests in charge, he wrote down specific rules and standards for both. In 1244, Dogen founded the Eiheiji temple in present-day Fukui Prefecture, where his teachings are still passed on today. I had an opportunity to partake of a special shojin meal that is offered only to invited guests of Eiheiji. The meal was served on two zen tray tables (see photo below).

The first tray held steamed white rice and miso soup. Placed above the soup was a vinegared dish, a local specialty made with the stems of yatsugashira, a type of taro. Above the rice was a simmered dish that included yuba soy milk skin, shiitake mushroom, deep-fried tofu and other ingredients. In the center of the tray was goma-dofu (tofu of ground sesame paste and kuzu starch), a dish in which Eiheiji places great importance. The second tray held sumashijiru (clear soup) containing nama-fu (wheat gluten) and tororo kombu (shaved dried kombu softened in vinegar). To the right of the soup was a vegetable dish of eggplant and shishito miniature sweet green peppers. At the upper left was a shira-ae dish of vegetables dressed with a mixture of mashed tofu and sesame. Placed upon a sheet of white shiki-gami paper was an auspicious treat of braided, deep-fried kombu.

Photo by Ayako Ehara, courtesy of Eiheiji

In shojin cuisine, soybean products such as tofu and yuba, along with fu, are important sources of protein. Sesame contains oil, calcium, iron and protein, and has been an essential ingredient in shojin cuisine long before the development of modern nutritional science.

Each year, on the anniversary of the death of Dogen, a two-tray meal is served in red-lacquered dishes on red-lacquered zen tray tables and offered at his memorial sanctuary. I was told that the dishes of this offering meal resemble those in my guest menu, with some variations. This kind of shojin fare is served not only in temples, but also at home and in restaurants that specialize in shojin-ryori. The spirit of these dishes—founded in gratitude for all life, wasting nothing—continues to be embodied throughout the heart of Japanese cuisine.