Respect for Nature

Washoku traditional dietary cultures of the Japanese were recently added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. In this year’s new Feature series, we take a close look at this unique Japanese cuisine, starting with how a respect for nature has shaped the origins of the Japanese diet.

Nature’s Bounty

A respect for nature is seen as part of the culture in every country, but it occupies a particularly important place in the hearts of the Japanese. The great poet Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) said that the sense of beauty shared by Japan’s leading artists—the great painter Sesshu (1420-1506) and the tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591), for example—came from yielding one’s body to the rhythms of nature and taking pleasure in the changing seasons. A keen awareness of how human life unfolds within the larger scheme of nature grew out of the ancient traditions of animism that form the basis of Japanese religiosity.

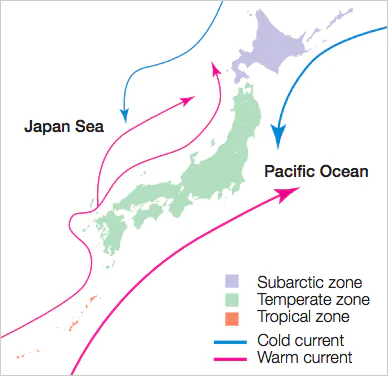

Japan’s food culture grew from this awareness. Food has always been considered as the bounty bestowed by our natural environment. That environment varies within Japan’s long archipelago, starting from the northernmost island of Hokkaido in the subarctic zone to the southernmost islands of Okinawa in the tropical zone, with most of the rest of the country midway in the temperate zone. This chain of islands, surrounded by seas where warm and cold currents meet, has a coastline that totals some 34,000 kilometers.

mixed sushi topped with sea bream sashimi

Along with the more than 4,000 varieties of fish that inhabit the country’s rivers and seas, shellfish and seaweed such as nori, kombu and wakame are popular ingredients on the Japanese table. The country’s territory is by no means large—about 70 percent is mountainous, making it unsuitable for large-scale agriculture—yet each year its abundant rainfall of some 1,700 millimeters flows into clear streams and irrigates rice paddies, fields and orchards. Japan’s seas, mountains and valleys are rich with all kinds of food ingredients.

Veneration of the Seasons

The monsoon climate around most of the archipelago creates four clearly defined seasons, and the dishes served and the ways they are prepared follow these seasons. For example, the especially tasty tai (sea bream) harvested around the time cherry blossoms bloom in spring—known as sakura-dai (cherry blossom sea bream)—is much prized by gourmands. Japanese daikon, harvested as winter approaches, is simmered and eaten with miso sauce—a simple, warming dish called furofuki-daikon, perfectly suited to an early-winter table.

Cooks pay special attention to the shun (peak season) for each ingredient, but the seasons are also divided into even finer increments. The period just before the shun when a vegetable or fish begins to appear on the market is called the hashiri—the first much-anticipated opportunity to enjoy the flavor for which one has waited a year. After the shun is mainly over, there is the nagori mature flavor that can be savored as the season gradually wanes. In this way, through the enjoyment of dishes that capture the flavors of each season, we feel the pleasure afforded by living in tune with nature.

Japanese have a way of thinking of food as resulting more from the power of nature than from the power of human beings. The farmer’s labor and the fisherman’s toils are naturally appreciated, but obviously that is not all. Rather, it is the role of nature that is seen as dominant, with human hands serving to assist and support in the harvest. People feel a certain piety with regard to the food that is received through the bounty of nature, and this is the basis of the words itadakimasu (“I receive”), customarily spoken before eating, and the sentiment gochisosama (“thank you for the meal”), that concludes the meal. Itadakimasu also expresses thanks to the person who has prepared the food; but at its core, the word carries a feeling of gratitude toward the universal, omnipresent spirit thought to abide within the food itself. Whether a plant or an animal, we obtain life-giving nourishment from it, and such gratitude naturally gives rise to a sense of reverence. When we were children, we were taught not to leave even one grain of rice in our bowls because it was wasteful and sure to bring down punishment from heaven. The admonition that one must not waste food is expressed in the word mottainai, which means, literally, “it is a pity not to be able to treasure the use of things.” The spirit of Japanese cuisine—of treasuring the bounty of nature and using everything without waste—is in close accord with current ecological concepts that call for conservation of our natural environment.

Sustaining Nature’s Spirit

Today, however, great changes are taking place in Japanese food culture, alongside a shift in Japanese attitudes toward both nature and food. Like so many other countries, Japan’s environment has been ravaged in the wake of industrialization, and its society is gripped by the vicious cycle of mass production and mass consumption. There are more and more young people with no experience in a primary industry such as agriculture or fisheries, and thus their connection with the environment and sense of respect for nature is often undeveloped.

Moreover, even though traditional food culture was based upon the use of ingredients provided by Japan’s own natural environment, its food self-sufficiency ratio has dramatically decreased and has fallen under 40 percent on a calorie supply basis. This is a result of Japan’s shift away from ingredients produced domestically toward cheaper imports. Foods imported from around the world all year round no longer reflect Japan’s own seasons, nor even the seasons of their foreign origins; who grew and who harvested them is unknown. Such conditions do not foster a sense of gratitude toward nature for the bounty of what we eat, and this leads to increased waste of anything that seems unnecessary—even if it can be eaten—and this waste leads to degradation of the environment.

These trends arouse concern as to whether the spirit that sustains the traditions of the Japanese table may be lost, and whether the Japanese awareness of being part of nature—along with their distinctive sensitivity to the changing seasons—may be eroding the very spirit that sustains the traditions of Japanese food culture. The listing of Japanese cuisine as a recognized UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage offers us a unique opportunity to revive and reinvigorate this prized aspect of our washoku traditions.

Isao Kumakura was born in Tokyo in 1943. He taught at Tsukuba University from 1978 to 1992; from 1992, he was professor at the National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka, where he was then named professor emeritus in 2004. He was director of Hayashibara Museum of Art, Okayama from 2004 to 2012. Since 2010, he has served as president of Shizuoka University of Art and Culture. Dr. Kumakura is the author of many publications on Japanese food culture and Japanese tea culture; his most recent work is Bunka to shite no Manaa (“Manners as Japanese culture”).