Italian Cuisine

Our current series is exploring some of the diverse international cuisines that are embraced in Japan. This second installment traces the history and evolution of Italian cuisine in Japanese food culture.

Italian food is very well-suited to the Japanese palate and is widely accepted here, not only as restaurant fare, but as an essential element in home cooking.

Early Italian Style

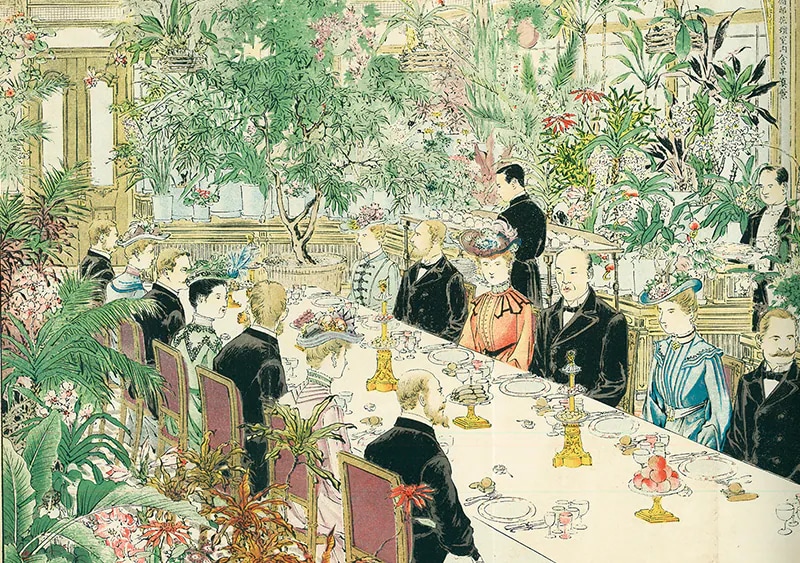

Courtesy of The Italia Ken

What is believed to be Japan’s first Italian restaurant was the Italia Ken, opened in Niigata in 1881 by Pietro Migliore, a native of Italy. In 1895, the Restaurant Toyoken in Tokyo is said to have been the first to serve pasta imported from Italy. The early twentieth-century best-selling book Shokudoraku (“The pleasures of eating”) introduced dishes like macaroni and cheese, and though macaroni may have been somewhat known among members of the upper class at this point, it was regarded more generally as part of Western cuisine, rather than as an ingredient in Italian cuisine.

Upon the outbreak of the Second World War, many Western foods, macaroni included, disappeared, but afterward, former Italian prisoners of war reintroduced Italian cuisine by opening restaurants in Kobe (Antonio’s; Donnaloia) and Takarazuka (Amore Abela) in Hyogo Prefecture, all of which remain in business today. Such restaurants catered primarily to those with the Allied Occupation. During the 1950s, Tokyo restaurants such as Sicilia and Nicola’s opened and served pizza and spaghetti in the style introduced from the US. Around this time, spaghetti made with a ketchup-based sauce appeared in Japan where it evolved and was later named Spaghetti Napolitan, which remains popular today. In 1960, the Tokyo restaurant Chianti opened and was patronized by members of the government as well as trend-setters. Chianti was more of a European-style restaurant, however, and the American-style dishes served in many eateries at the time represented mainstream Italian cuisine in Japan.

Mention should be made of the Kabe No Ana (“hole in the wall”) restaurant chain that began in Tokyo in 1953, when Japanese were still unfamiliar with Western-style flavors. This company pioneered wafu Japanese-style spaghetti dishes geared specifically toward local palates, including spaghetti with tarako salted cod roe, and with umeboshi pickled Japanese apricot and shiso perilla—both of which are now commonly served throughout Japan.

Eventually, spaghetti noodles and canned meat sauces manufactured in Japan came onto the market, and from the 1960s, both Spaghetti Napolitan and meat-sauce spaghetti quickly became familiar to the public with their appearance on menus of kissaten Japanese-style coffee shops.

Authentic Flavors

Japan’s interest in other countries increased along with the country’s growing affluence during the rapid economic growth period of the 1960s, and thanks to the 1970 Japan World Expo in Osaka. Aspiring chefs traveled to Italy for training, and upon their return, restaurants began to offer authentic Italian cuisine, unfiltered by American influences or imitations of what was considered “Italian-style.” During the 1970s and early 1980s, restaurants serving authentic Italian cuisine appeared, one after another—and it was also in the 1970s that the Japanese government lifted import bans on durum flour and canned tomatoes.

Influenced by the emergence of nouvelle cuisine in France around this time, Italian chef Gualtiero Marchesi led the nuova cucina movement, which favored the proper heating of ingredients to enhance their flavors, the use of light and subtle seasonings, and an attention to the colors of ingredients. In Japan, prosperity during the second half of the 1980s fueled a boom in the popularity of Italian cuisine, and Japanese chefs exposed to the nuova cucina movement in Italy began to devise new styles of Italian food, unconstrained by tradition. The breakdown and reconstruction of traditional Italian cuisine and the search for lighter flavors, as well as the serving of cold pasta, led to the creation of dishes that were entirely new to Italian cooking.

The 1990s were highlighted by the media-stoked tiramisu fad and a booming interest in wine-drinking, with luxury wines such as Super Tuscan appearing on the market. The ban on imports of prosciutto ham was lifted, and shops serving thin crust Naples-style pizza, as distinct from American pizza, began to emerge. The numbers of casual-style restaurants serving Italian dishes increased, allowing diners the opportunity to experience a broader range of Italian dishes and become more familiar with them. The rapid spread of the Saizeriya Italian-food chain of family restaurants also contributed to the mass popularization of Italian cuisine.

International Food Cultures

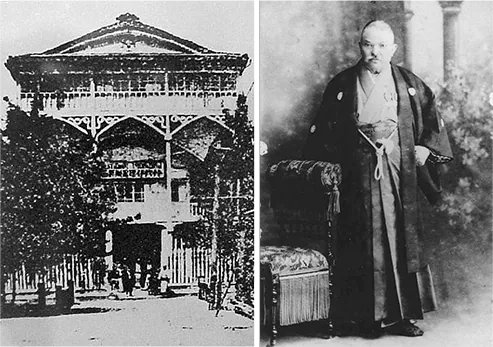

Courtesy of Al-ché-cciano

Since the 1990s, the diversification of restaurant-based Italian cuisine has continued. There are restaurants that seek ever-more authentic regional Italian cuisines, restaurants that feature the idiosyncratic tastes of an individual chef, and restaurants that fuse Japanese local ingredients and tastes with the simple cooking methods known to Italian cuisine, as represented in dishes created by Chef Masayuki Okuda of Al-ché-cciano. A unique Italian cuisine has therefore arisen, conceived through purely Japanese interpretations. Italian cuisine in Japan has not only evolved through the influence of chefs and restaurants: buoyed by the increasing availability of dried pasta and retort-prepared sauces, it is now a standard component in home cooking.

Indeed, with dishes like pizza and pasta well-established as prepared foods or delivery fare, Italian cuisine is now a familiar part of the food culture of Japan. In contrast to French food, with its haute cuisine associations, Italian food has found a place in daily life, taking on its own unique identity beyond the conventional categorization of “Western food.”

The history of Italian cuisine in Japan is one more clear example of the way in which food cultures of other countries have been incorporated into this country’s diet. It also reveals the enthusiasm that Japanese have for cuisines of all kinds.

Courtesy of Jun Hasegawa

Courtesy of Jun Hasegawa