Balanced and Healthy

In the second installment in our series on washoku, we focus on its healthy aspects, and how Japan’s traditional cuisine makes for a well-balanced diet.

One of the main reasons Japanese foods such as sushi have become so popular around the world is that they are considered to be healthy. The spread of Japanese cuisine (washoku) overseas began in the U.S. during the eighties as a gourmet rarity; this was against the backdrop of Japan’s remarkable economic development and a growing awareness of its long life expectancy, and it was concluded that Japanese health and vigor were a direct consequence of the country’s diet.

Dietary Guidelines

After the 1960s, an increase in heart disease from nutritional imbalances was a major U.S. health concern. In 1977, the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs established a set of nutritional guidelines in its Dietary Goals for the United States, commonly called the McGovern Report. These included recommendations that carbohydrates be increased up to 55% to 60% of total calorie intake; that fat be reduced to less than 30% of total calorie intake; and that fish be substituted for meat to avoid saturated fatty acids.

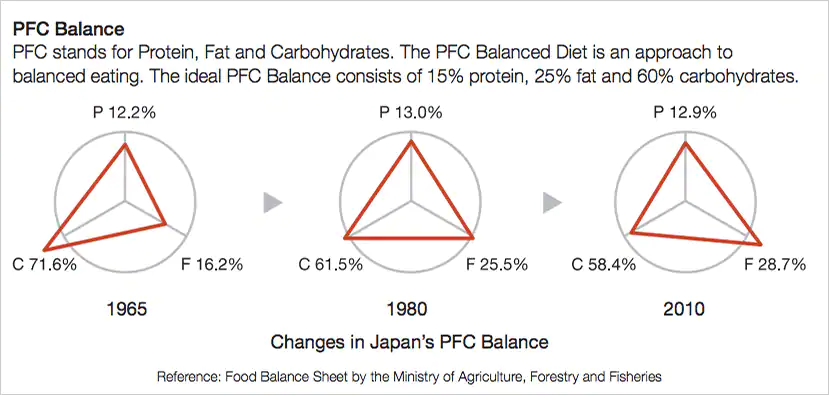

By around 1980, Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries noted that a balanced Japanese diet comprised 15% protein, 25% fat and 60% carbohydrates—virtually identical to the Dietary Goals of the McGovern Report. The Ministry proceeded to issue these figures as the country’s dietary guidelines under the term “the Japanese-style diet.”

Historically, however, the Japanese diet was not always so balanced. Figures indicate that during the mid-sixties, Japanese generally consumed too many carbohydrates, along with high levels of sodium. Gradually, as the country experienced economic growth and prosperity, better-quality proteins including meat, fish and dairy products became more readily available. This led to overall greater intake of protein and calories, which balanced the intake of carbohydrates. By the 1980s, statistics revealed that an ideal dietary balance had been attained—an ideal diet that closely followed traditional washoku eating patterns.

Washoku Style

What are the patterns that define a washoku meal? First of all, it consists of four components: rice as the staple, a soup, side dishes and Japanese pickles. These elements are consumed together in order to mix the simple taste of the rice with the more richly seasoned side dishes, thus creating a harmony of combined flavors. There is a tendency to eat Western-style dishes separately; a washoku meal, however, is always eaten by integrating the rice, side dishes, pickles and soup together or in turn, and finishing them at the same time.

Let us consider the side dishes. Probably the favorite side dish of Japanese is sashimi, slices of raw fish. Certainly all kinds of seafood are well-suited to the washoku meal: sakuradai (sea bream) harvested around the time cherry blossoms bloom in spring; katsuo (bonito) in early summer; freshwater ayu (sweetfish) in midsummer; sanma (Pacific saury) in autumn; buri (yellowtail) loaded with tasty fat in winter; as well as maguro (tuna) and aji (horse mackerel) throughout the year. The intake of blue-backed fish such as tuna and mackerel can help reduce “bad cholesterol” in the blood, because the oil and fat they contain are rich in unsaturated fatty acids such as DHA* and EPA, unlike beef or pork, which are high in saturated fatty acids. When meat is used in a washoku side dish, it is typically in small quantities.

Vegetable proteins are also a significant facet of washoku. Soybeans, which appear most often in the form of tofu or natto (fermented soybeans), are frequently part of the menu. Root vegetables, leafy vegetables and various iodine-rich seaweeds also feature regularly on the Japanese table. Together, all of these characteristics of washoku—particularly the consumption of rice as the main staple—promote a balanced diet and prevent excess intake of protein and fat.

Changing Tastes

Another essential feature in the healthy Japanese diet is its emphasis on umami.

Just over a dozen years ago, the umami taste receptors in human taste buds were identified, and umami was formally recognized as the fifth independent basic taste, alongside sweet, sour, bitter and salty. The Japanese developed methods of extracting umami such as glutamine acid and inosinic acid from kombu seaweed and katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes) more than 500 years ago, and this taste has long been considered a fundamental constituent of Japanese food. Umami enhances flavors in harmony with other seasonings, and brings out the intrinsic taste of the ingredients themselves. As a result, there is a decrease in the amount of seasonings required, which in turn leads to lower sodium intake.

Today’s Japanese eating habits are changing, however. From the ideal nutritional balance of the eighties, more recent statistics from 2010 indicate that the Japanese diet has become more Westernized, causing an increase in fat intake and a rising number of patients with lifestyle-related diseases. The country’s meat consumption is also on the rise, whereas its rice intake is decreasing.

The recent listing of washoku traditional dietary cultures of the Japanese as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage has made us recognize anew the advantages and benefits of our traditional diet, and has served to inspire and motivate us to pass those benefits on to future generations.

- *DHA (docosahexaenoic acid); EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid)