Annual Events and Traditions

Sake, Japan’s traditional brewed alcoholic beverage, is made from rice, water and rice koji fermentation starter. Our new feature series introduces this venerable drink and how it has influenced Japan’s food culture, starting with a look at the essential role sake has played in Japan’s rituals and ceremonial events since ancient times.

Sanctity of Sake

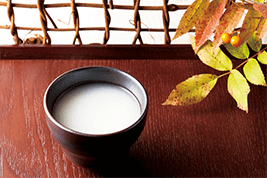

the most ancient form of sake

Sake has been produced since ancient times as an inseparable part of sacred rites and rituals that are dedicated to divine spirits. Indeed, it may be said that the origins of sake arose as ritual offerings to these spirits. An old adage affirms that Japanese divine spirits have a liking for sake. The sa is a prefix that can be interpreted as the idea of “purity.” We find the same sa in words like saniwa (sacred ground) and saotome (maiden planting rice), and it is understood as something that reflects a pure state. The ke refers to “food,” and thus sake is an offering that was considered to be particularly pristine.

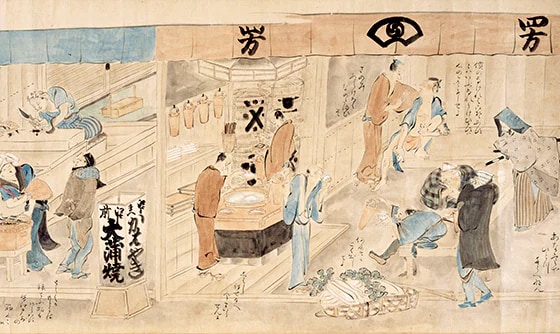

In olden times, sake was brewed for festival events. Sake brewing itself was said to be the work of the divine spirits, as expressed in an ancient poem by the master brewer Ikuhi, ancestor of the master brewer of Oomiwa Shrine in Nara Prefecture; the divinity of this shrine is associated with the making of sake. Sake is produced with painstaking care from rice, which was highly honored as representing chikara, meaning growth or power; in other words, it is nourishment that contains divine power. Thus it was called sake, or “sacred food,” and was considered a medium of communication with the divine. Probably the very oldest form of sake is unfiltered or “cloudy” nigori-zake.

Ritual and Ceremony

Even today, sake is essential to any sort of sacred rite. One of the definitions of a ritual lies in the act of food and drink being partaken as if dining together with the gods, where people and the gods are thought to mingle during a banquet. This is best reflected in the rite of naorai, which conveys the meaning of release from acts of purification that are practiced before participating in sacred rites. This is not some sort of sake-drinking affair for pleasure; it is entirely about sake as ritual, where the sake itself serves as a profound intermediary between humans and their gods.

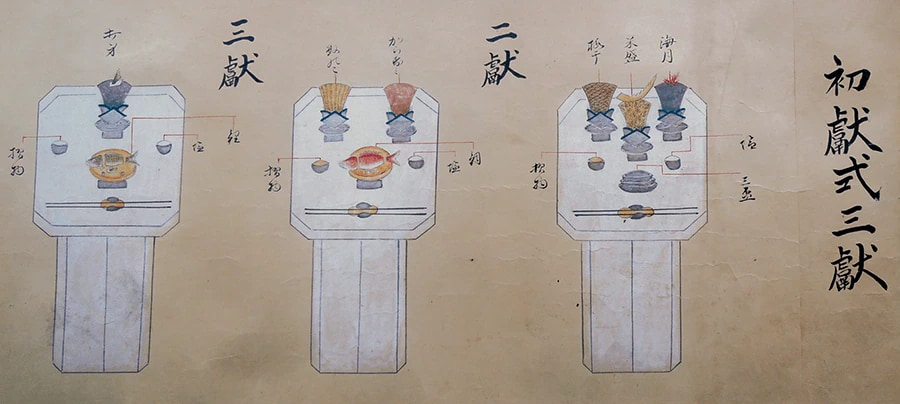

The most notable way in which naorai has been passed down is still seen today in those festivities held at shrines immediately following a ceremony. Sake that has been offered to the gods is taken down from the altar and distributed among the organizers of the ceremony. Thus naorai refers, in the strict sense, to the sharing or union with the gods to be felt in partaking of the very drink “sipped” by those gods. The procedures or ceremonies of the sake rite are not necessarily standardized, but one well-known formal procedure is the shiki-san-kon or “three formal rounds.” This stems from the term shikikon, the formal partaking of sake, in which shiki signifies ritual, while kon refers to sake and an accompanying bit of food. In the shiki-san-kon ceremony, guests receive three servings of sake, referred to as san-kon, each in a different cup. To partake of sacred sake that has been offered to the gods, refreshing one’s mouth with food, and drinking three times with deep respect and reflection, represents a ceremonial kind of mutual promise or contract; in this case, with the divine. And it is believed that through such a ceremony, people may avail themselves of the blessings of the gods.

Confirming a Vow

The formal shikikon ceremony is thought to have begun as a palace rite during the Heian period (794-1185). Later, with the development of the warrior class in succeeding centuries, the form became established in the ritual servings of sake as a way in which to confirm a pledge or vow. Warriors going off to battle, for example, would gather to exchange such cups, confirming their solidarity and valor. Favorite delicacies served with the sake on such occasions were those with auspicious names: uchi-awabi (also called noshi-awabi, thinly stretched abalone); kachi-guri (dried chestnuts); and kombu (kelp). Their names reflected good fortune: uchi means “strike” or “overwhelm”; kachi signifies “to win” or “victory”; kombu evokes the word yorokobu, or “happiness” and “delight.” Together they convey uchi-kachi-yorokobu: “we strike, we win, we rejoice.” The word for a combination of light foods chosen to suit the occasion of ceremonial servings of sake is kondate, the contemporary term for “menu,” wherein kon refers to shikikon.

The custom of serving sake with a bit of food continues today. When one orders sake or another alcoholic beverage at an izakaya Japanese-style pub, they invariably receive a small dish of what are referred to as o-toshi or o-tsumami refreshments to accompany their drink. Even when riding Shinkansen bullet trains, service includes sales of o-tsumami to eat with the alcoholic beverages that are sold; this custom represents a very long and unbroken tradition.

Other forms of this ancient custom are seen today in traditional New Year’s ceremonies held in some local communities and in societies of craftsmen, as well as in the exchange of nuptial cups at a marriage ceremony, called san-san-ku-do—three rounds of three cups. Until several decades ago, there were customs of exchanging cups to affirm a dutiful relationship reflective of parent and child (oyako sakazuki), as well as cup exchanges that expressed a relationship evocative of siblings (kyodai sakazuki), as a supportive way of confirming a vow or pledge. This exchange of cups as symbolic of solidifying agreement or mutual promise is uniquely Japanese.

Then there are reiko, rituals that involve sake which are conducted at parties. When someone comes late to a party, having missed the opening formalities, he is often urged to “catch up” with the drinking by having a quick three rounds of drink. In any case, after the reiko formalities are over, the informal enjoyment—bureiko—can begin. Today, beer is more often used for the toast at banquets and parties, so words like shikikon and reiko are falling into disuse. However, those customs practiced when Japanese drink can be traced back to sake.

Sake in Japan is more than just for celebrations. It possesses a rich history as a special libation that forms and solidifies bonds between one person and another, and between people and the divine spirits.

Noritake Kanzaki was born in 1944. He is a specialist in Japanese folklore and president of the Institute for the Culture of Travel. He serves on the Council for Cultural Affairs of the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and as guest professor at the Tokyo University of Agriculture. He is chief priest at the Usa Hachiman Shrine in Okayama Prefecture. His many published works include Sake no Nihon bunka: Shitte okitai o-sake no hanashi (“Sake in Japanese culture: convenient stories to know about sake”); Shikitari no Nihon bunka (“Manners and customs of Japanese culture”); and Edo no tabi bunka (“The culture of travel in the Edo period”).