Distinctive Customs of Drinking Sake

This final installment in our series about Japanese sake takes a closer look at the traditions and foods that revolve around social drinking.

Snacks with Sake

Japan has a few unusual practices related to the drinking of sake. One is that sake drinkers typically nibble on dishes of tidbits called sakana between sips of their drink. This snacking while drinking sake, called kuchitori-sakana, is distinct from eating appetizers intended to stimulate the appetite. Even without food to accompany the sake, a knowledgeable sake drinker will, at the very least, lick a bit of salt between sips. Sake is very high in sugar content, so taking a tiny morsel of salt refreshes the palate and enhances the pleasure of the drink.

This long-established enjoyment of sakana with sake remains popular even today, as any visitor to a modern izakaya Japanese-style pub can attest. After ordering sake—or any alcoholic beverage for that matter—a sakana snack invariably appears as part of the order. These small and savory dishes are a customary and essential element of Japan’s sake culture.

Another time-honored element in sake-drinking culture is sakazukigoto, a kind of ritual in which each participant drains three cups of sake in three sips each, in order to seal a pledge or cement a deal. It is still performed in marriage ceremonies today. An accompanying tray of food might include kombu, dried squid or umeboshi pickled Japanese apricots.

Ritual and Custom

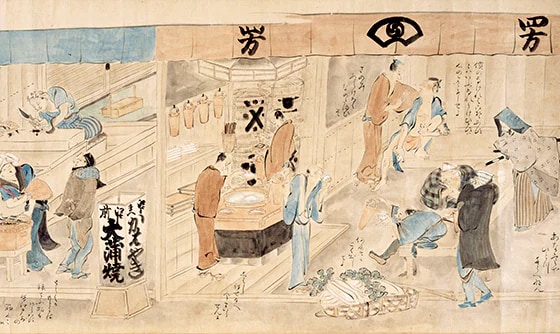

Also distinctive is the custom of warming sake before drinking. The practice of pasteurizing sake can be traced back to as early as the fourteenth century. At that time, it was difficult to preserve the beverage for long periods, especially in those regions where temperature and humidity are high in spring and summer. Brewers thus pasteurized their sake before shipment to maintain its quality. Awareness of the antibacterial advantages afforded by this hint from brewers may have prompted people to warm their sake before imbibing. A further reason may be that warmed sake brings out the best in the variety of simmered dishes that were originally served at festive drinking parties. The two make for a very satisfying match. The drinking of warm sake with simmered dishes is a relatively new tradition, having become popular during the eighteenth century in urban areas such as Edo (Tokyo), Kyoto and Osaka, as dining out developed as an industry, and as simmered dishes were customarily served at shops and food stalls.

Social Changes

It was much later that the concept of social sake-drinking spread from the cities to rural agricultural and fishing villages, where sake had previously been brewed privately just for special observances and presented as an offering, which people would then drink “together with the gods” during a rite called naorai. It wasn’t until around the end of the nineteenth century that sake was purchased as a distinct commodity in both urban and rural areas throughout Japan, and the act of drinking sake moved beyond strictly ritual significance towards the broader social role it plays today. This way of drinking sake transformed once-special events to ordinary occasions, and such opportunities in turn increased the demand for sake.

One major factor behind this shift was that, in addition to the traditional banquets held to celebrate annual and seasonal events, semi-official banquets called enkai were conducted more frequently following the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Enkai included parties organized by companies and government offices, as well as celebrations to send men off to battle and welcome them back during Japan’s times of war with China (1894–95) and Russia (1904–05). Like social drinking, enkai originated in urban areas and gradually became more widespread. Testimony to the banquet boom of those times was the sharp increase in the quantity of sake produced, as more sake breweries came to be established in various parts of the country from around 1897. Indeed, that increase continued to rise to the point where sake taxes collected by the national government came to account for a full third of the country’s tax revenues.

region accompany sake.

While the word “banquet” is used here, an enkai was not intended to be a lavish dining experience, but rather an opportunity for people to drink together and forge closer bonds. Such occasions sometimes went on for hours. The food served at these drinking parties, moreover, was prepared expressly to be eaten while drinking sake, and was quite different from appetizers or side dishes that might accompany a regular meal. enkai served classic, kaiseki course-style Japanese cuisine that consists of five dishes, served simultaneously on a tray-table: rice; o-sumashi clear soup; namasu vinegared vegetables, or raw seafood, or su-miso-ae vegetables with seafood dressed in vinegared miso; a simmered dish flavored with soy sauce; and grilled, salted fish. The amount of rice was very small—only about three mouthfuls—and the soup had a moderate salt content. Both were intended to complement copious amounts of sake: the rice to assuage immediate hunger, and the soup to cleanse the palate. In later years, sashimi was served instead of grilled fish. The soy sauce that accompanies these delicate slices of raw fish is the integral element that makes sashimi the ultimate in sakana snacks. To wrap up these drinking parties, a substantial serving of rice, a bowl of miso soup, and tsukemono pickles were served to finish with a “proper meal.” This practice continues even today at parties where sake is served. Quite a long succession of tasty sakana dishes may be offered, but eventually it is all brought to a conclusion with the shime no shokuji, or “closing meal.”

This tradition of mingling specific, customary foods while drinking sake is unlike typical Western social drinking, and also differs, for example, from how wine is consumed during course-style meals. Japanese sake might perhaps best be considered a delightful aperitif that characterizes the country’s distinctive culture of enjoying sake while forging bonds.