Courtesy of Kanagawa Museum of Modern Literature

French Cuisine

Japan’s eclectic dining scene has been informed by foods from around the world. Our new Feature series explores the history of how various international cuisines took root in Japan and evolved, starting with the impact and enduring appeal of French cuisine.

The true measure of the significance of French cuisine in Japan is best reflected in the high rankings it regularly receives in the country’s Michelin Guide. Let me briefly relate how French food attained such recognition in Japan, starting with its introduction here in the late nineteenth century.

Diplomatic Cuisine

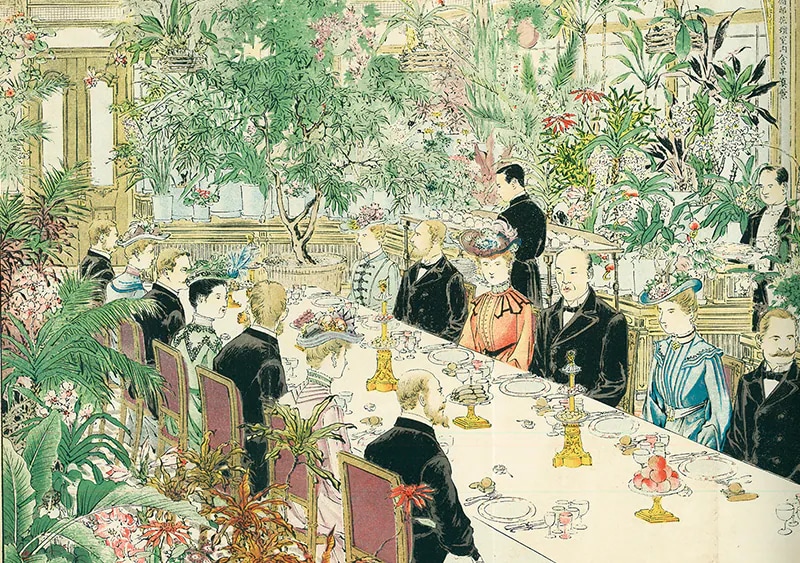

Courtesy of Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture

Perhaps the first official banquet in Japan to serve French cuisine was held in 1867 at Osaka Castle, when the last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837-1913), entertained the consuls of Britain, France, the Netherlands and the United States. But the definitive introduction of French gastronomy here begins with official government banquets and those served in the court of the emperor during the Meiji era (1868-1912). Banquet menus of this time reveal that, while there was some substitution of those ingredients which could not be obtained in Japan, the dishes presented were nearly identical to those served at French tables in the late nineteenth century.

The Meiji government aimed to modernize the country, and Japan’s government and business leaders clearly recognized the diplomatic significance of food, particularly French cuisine. Through their initiative, the Tokyo Tsukiji Hotel, the Tsukiji Seiyoken restaurant and the Rokumeikan banqueting house were purpose-built to entertain prominent guests from Japan and overseas—and each served authentic French cuisine. The Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, established in 1890, also functioned as the state guest house of the Meiji government. The Imperial Hotel paved the way for French cuisine in Japan from the late 1920s, as its own chefs were sent to train at the Hotel Ritz in Paris.

Because of these top-down efforts by Meiji government and business sectors to introduce French cuisine, public perception here has historically regarded French food as formal and somewhat unapproachable. Yet in retrospect, Japan’s robust embrace of French cuisine in the late nineteenth century was significant in establishing its fundamental infrastructure here, which in turn produced an environment that was highly receptive to its further development.

Seeking Authenticity

Before and after the Second World War, the advancement of French cuisine in Japan came to a standstill, leading to considerable variance with the authentic cuisine. Two historical milestones helped to close this gap: the opening of the French restaurant Maxim’s de Paris in 1966 in Ginza, Tokyo; and Japan’s World Expo in Osaka in 1970. Expo ’70 happened to coincide with the emergence of France’s enormously influential nouvelle cuisine. Not only did the France Pavilion introduce many of the Expo’s 64 million visitors to French food, countless young Japanese chefs working in the Pavilion’s kitchens also encountered true French cuisine for the first time. These chefs set forth en masse to France on their own initiative to master the skills of French cuisine with passion and commitment. Without a doubt, these intrepid Japanese chefs laid the foundations for French cuisine in late twentieth-century Japan.

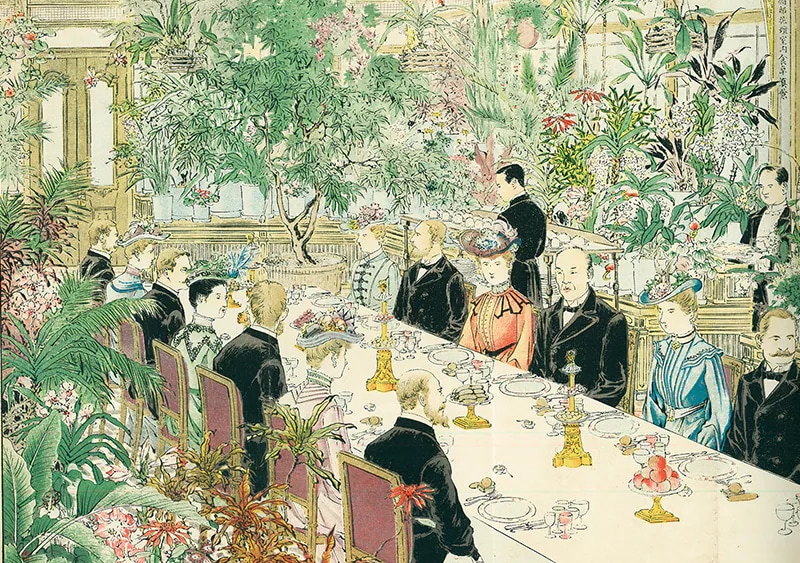

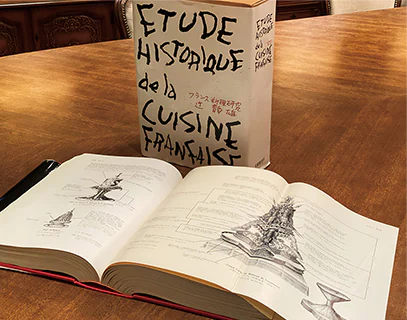

Around this time, my father Shizuo Tsuji, founder of the Tsujicho Group, became involved in deepening Japan’s adoption of French cuisine. He invited numerous French chefs to Japan for professional culinary arts exchanges; and through his historical research on French cooking, he made it possible for Japanese chefs to focus on advancing their own techniques and the profession as a whole. He published essays and books on the cultural role of food in French society, and these played a part in creating a broader Japanese appreciation for French food and for the rich culture that nurtured it.

Courtesy of Tsuji Culinary Institute

Courtesy of Tsuji Culinary Institute

Courtesy of Tsuji Culinary Institute

A Global Shift

As both cooks and consumers became more sophisticated during the period of Japan’s rapid economic growth in the late twentieth century, the country’s French cuisine entered its golden age. Yet no matter how skillfully chefs here mastered its arts, as long as they continued to pursue the “authentic” cuisine of France itself, they were faced with an insurmountable wall. Although innovations in transport and distribution made it possible to utilize the same ingredients as those available in France, it was only natural that nuances, however subtle, would exist.

Courtesy of HAJIME&ARTISTES INC.

Through twenty-first century globalization, state-of-the-art cuisines built upon the French culinary platform have been appearing around the world, and the ways in which people view food and flavor are diversifying. Culinary expressions of terroir or local ethos that make active use of scientific knowledge and technologies have become the global trend. This comprehensive shift has been a gift to Japanese chefs, allowing them to distance themselves from “authentic French” and pursue their own unique, equally valid, interpretations. We see this in the sophisticated, meticulous presentation of dishes by chef Hajime Yoneda at HAJIME in Osaka; and in the work of chef Yoshihiro Narisawa at NARISAWA restaurant in Tokyo, who created the new genre of “Innovative Satoyama Cuisine” as an expression of Japanese terroir. The cuisine of chefs such as these, who compete with confidence on the world stage, reflects the polish and refinement they wield. Their art attests to the fact that they have not only elevated the French cuisine they have mastered, they have revolutionized it. The greatest appeal of French cuisine in twenty-first century Japan may be found in its diversity and in the generational breadth of its chefs. Alongside these innovative styles, there are other more orthodox, yet ingenious approaches. There is bistro fare that reflects French country food, and versions that draw upon ingredients grown in Japan’s distinctive natural environment. All are firmly grounded in fundamental skill—and this indeed is the rich harvest of more than 150 years of French cuisine in Japan.

Courtesy of NARISAWA

Yoshiki Tsuji was born in 1964 in Osaka, and educated in the UK and the US. He is chairman and head of the Board of Directors of Tsuji Culinary Institute. His numerous publications encompass the subjects of the modern transitions of gastronomy, and Japanese cuisine. He was awarded France’s National Order of Merit in 2018.