Chinese Cuisine

Japan’s food scene comprises a delicious and diverse range of international cuisines that have influenced—and been influenced by—Japanese food culture. This final installment of our Feature reflects on the historical and cultural contexts of Chinese cuisine in Japan.

Enjoyed in restaurants and at home, Chinese food is widely embraced in Japan. This may be because China and Japan fall into the sphere of East Asian food culture, and the two countries have quite similar eating patterns and customs. Despite some regional differences, rice is the staple of both diets and meals are eaten with chopsticks. There is also a flourishing population of Chinese living in Japan who sustain vibrant Chinatown communities in Yokohama and Kobe.

Early Influences

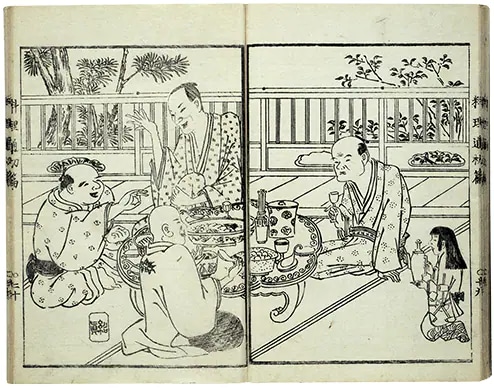

Japan’s national seclusion policy (1639-1853) during the Edo period restricted most international trade, with the exceptions of the Netherlands and China, which were permitted to engage in import-export activities at the port of Nagasaki.

Shippoku banquet cuisine emerged from such interchanges in Nagasaki as a fusion cuisine characterized by the mingling of Japanese elements with essentially Chinese dishes. By the early nineteenth century, Shippoku had spread to the Kyoto-Osaka area as well as to Edo, present-day Tokyo.

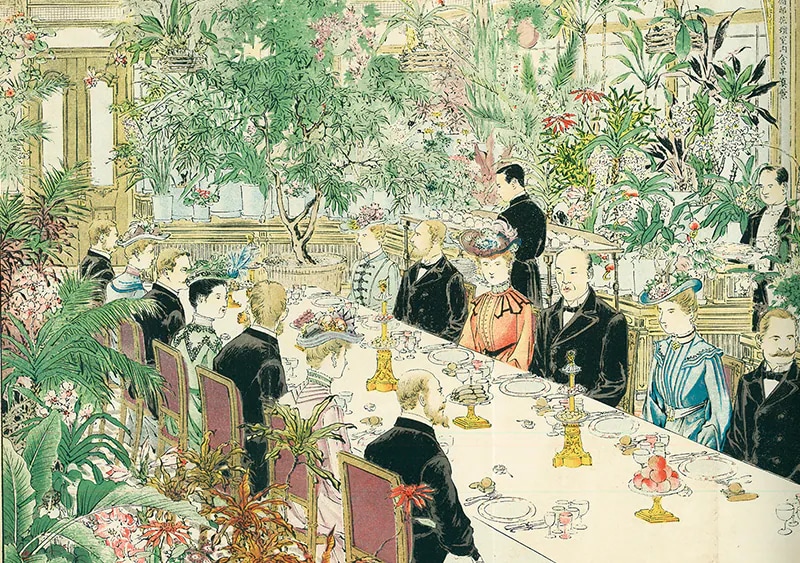

During the Meiji era (1868-1912) the national edict against eating meat was lifted and, by the late nineteenth century, restaurants that included the Kairakuen in Tokyo began to offer authentic Chinese cuisine. The Kairakuen was established in 1883 with capital investment by business leaders, specifically for the purpose of cultivating friendly relationships between Japan and China, and it served as an upmarket gathering place. There was also a proliferation of popular restaurants, such as Ishingo, catering to many Chinese who came to study in Japan. The cooks in these establishments were primarily from China.

From this time onward—and particularly during reconstruction following the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake—the number of Chinese restaurants in Tokyo grew steadily. This included large luxury establishments with banquet rooms, as well as casual eateries that catered to the general public. In the late 1920s, as Chinese restaurants became more generally accessible, women’s magazines began to introduce Chinese cooking, and the cuisine began to appear on household menus.

Postwar Benchmarks

There was more rapid growth of Chinese restaurants in the 1950s. One of these, Chugoku Hanten, was the pioneer of sophisticated Guangdong-style cuisine in Japan. Similarly, the Szechwan Restaurant, led by the legendary Chef Chen Kenmin, was instrumental in introducing genuine Szechwan foods such as mapo tofu in spicy ground meat sauce, and prawns in chili sauce. Both restaurants trained countless chefs; the Szechwan, in particular, evolved as a major force in the Chinese restaurant industry through the trained cooks and chefs working at its many affiliated restaurants. At the same time, buoyed by a robust economy, the standards of Chinese cuisine in Japan improved exponentially.

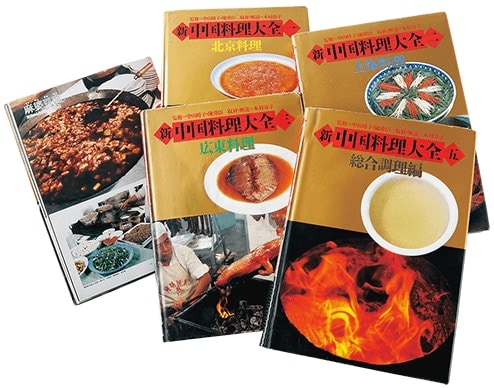

Around 1960, Tokiko Nakayama, then professor at Ochanomizu University, led a formal study of “authentic Chinese cuisine” involving scholars and chefs, who gathered at Yushima Seido Confucian sacred hall in Tokyo. Their research on Chinese food culture was based on extensive resources and fieldwork. Among those participating in this research was Rokuro Kozasa, founder of the Chimisai restaurant. Chimisai perpetuated the spirit of this invaluable project by providing a learning environment for aspiring chefs, and is also known for its early initiatives to encourage the cultivation and propagation of Chinese vegetables.

In the run-up to the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, numerous chefs were invited from Taiwan and Hong Kong to oversee Chinese restaurants that were established in large hotels in and around Tokyo. These restaurants ultimately served the latest dishes at the highest levels of quality, and therefore boosted the prestige of Chinese cuisine at a time when most people still associated hotel dining with French cuisine. This contributed to the expansion of luxury Chinese cuisine.

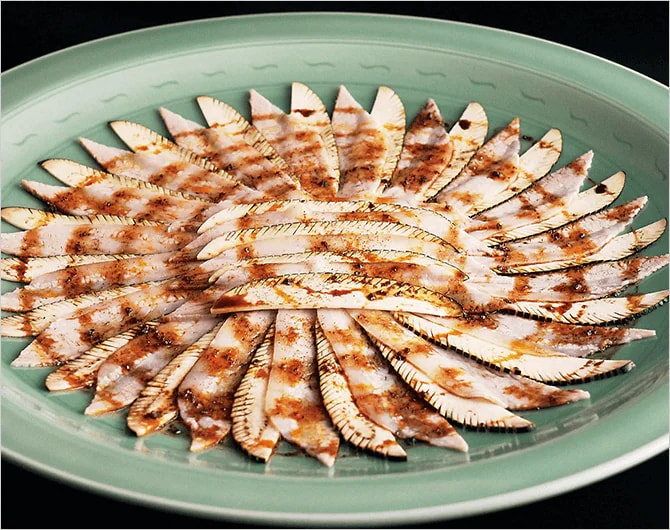

Courtesy of Wakiya Corporation

During the 1970s, a trend known as Nouvelle Cuisine Chinoise gained momentum under the influence of French cuisine in Hong Kong—a movement which became notable in Japan as well. Chef Yuji Wakiya presented a new style of Chinese cuisine that was served, not on large platters, but as small, attractively arranged dishes on individual plates at his restaurant, Wakiya Ichiemi Charou. His innovative way of presentation appealed to many, including younger generations, and helped broaden the acceptance of Chinese cuisine.

Present and Future

Courtesy of Sazenka Inc.

Until the 1990s, fine Chinese dining was primarily encountered in hotels and larger restaurants, but since around 2010, small privately owned restaurants have increased. The 2021 Tokyo Michelin Guide named Sazenka as the very first three-star Chinese restaurant since the first Tokyo edition was published in 2007. Chef Tomoya Kawada at Sazenka creates unique Chinese dishes founded on established Chinese culinary techniques, together with his own Japanese sensibility and experience, nurtured through his apprenticeship at Michelin-starred Japanese restaurant RyuGin. This genre of Chinese haute cuisine, as refined in Japan, is sure to continue to evolve.

Meanwhile, ramen noodles—whose origins can be traced to China, and originally known to the masses as shina soba Chinese noodles—are also evolving in distinctive ways, not only in Japan, but around the world. This well-loved noodle dish continues to make its mark globally as a leading example of Japanese cuisine.