Tracing the Old Kombu Route

Our current Feature series traces Japan’s traditional food byways. In this second installment, we explore the ancient routes by which kombu was conveyed throughout the country from its origins in northern Japan.

by Masami Ishii

Serving Good Fortune

Many traditional events and ceremonies are disappearing in Japan today in the face of changing lifestyles, but the custom of associating certain things with good fortune remains. The dishes served and ornaments displayed on New Year’s Day or at weddings, for example, are intended to create as auspicious and happy an occasion as possible.

One of the items prized for its role as a symbol of good fortune and happiness is kelp, a species of seaweed. The Japanese word for kelp is kombu or kobu, which sounds very much like the word for happiness or celebrate—yorokobu—and so kombu often appears in some guise during special occasions.

The Travels of Kombu

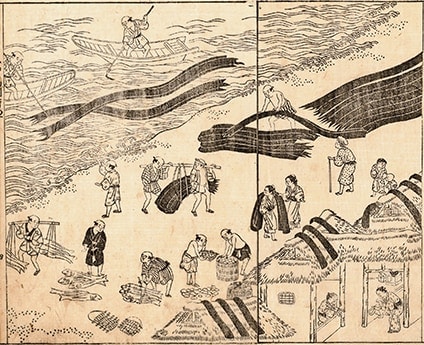

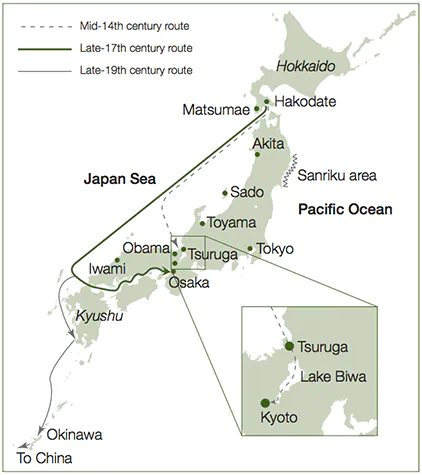

Edible kombu is produced only along the coasts of Hokkaido and the northeastern part of Japan’s main Honshu island in the Sanriku area, where warm and cold currents of the ocean meet. Records show that in the eighth century, the native Emishi people of northern Japan presented gifts of kombu to the Imperial Court in Nara; this food did not circulate as a market product, however, until centuries later. Around the mid-fourteenth century, the island of Hokkaido, then known as Ezochi, was developed and routes of transport connected it to ports in Honshu, along the Japan Sea. After arriving at ports such as Obama and Tsuruga (both in present-day Fukui Prefecture), kombu was transported overland to Kyoto and Osaka, and it became more widely known. Around this time, uga-kombu (fine-quality kombu) produced near Hakodate was mentioned in a common school textbook of that time, the Teikin orai. Kombu was also much featured in popular culture, as in the comic Kyogen play Kobu-uri (“The kombu seller”).

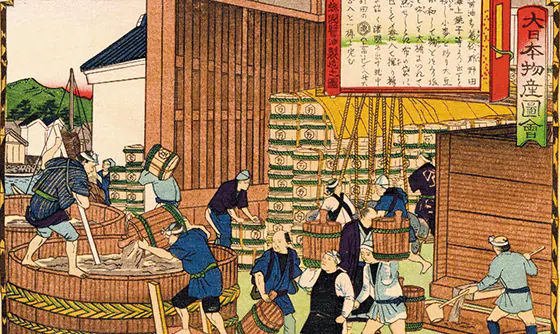

an illustration from the book Nihon sankai meibutsu-zue (1797).

Courtesy of National Diet Library digital archives

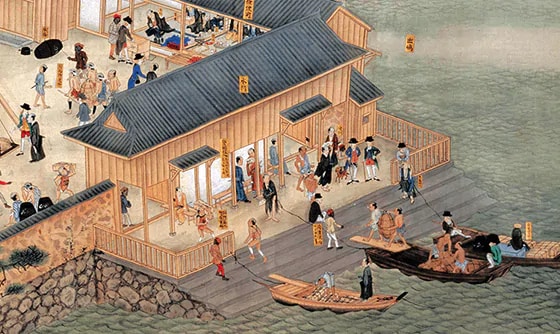

After the wealthy merchant Kawamura Zuiken (1618–1699) improved transport routes along the western side of Honshu under orders of the shogunate in the late seventeenth century, kombu could be shipped to Osaka. Carrying goods in large quantities, the great coastal transport boats known as kitamae-bune plied the routes between Matsumae and the commercial capital of Osaka.

Kombu was primarily consumed in Kyoto and Osaka, and the remainder was shipped eastward to Edo (present-day Tokyo), the seat of the shogunate government, or exported to Qing Dynasty (China) via the Ryukyu Dynasty (Okinawa). In the late nineteenth century, it is said that the highly profitable kombu trade via Okinawa, then controlled by the Satsuma domain of Kyushu, was the source of vast wealth that was eventually used in overthrowing the shogunate.

Regional Kombu Cuisines

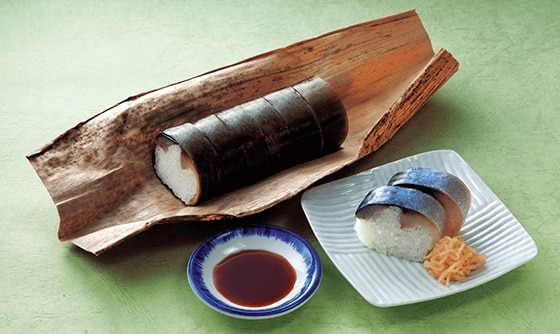

Kombu was prepared in different ways along its various trade routes, and so helped shape the distinctive food culture of each region. In Toyama on the coast of the Japan Sea, people are partial to sashimi marinated between sheets of kombu (kobujime); even kamaboko fish-paste loaf is wrapped in kombu. In Tsuruga, kombu is shaved paper-thin to make oboro-kombu; and in Kyoto, it is used to make the subtly flavored dashi stock that led to great refinements in Kyoto cuisine. In Osaka, the use of kombu led to the creation of side dishes such as tsukudani, soy sauce-flavored kombu.

In old Edo, meanwhile, dashi stock was commonly made from dried bonito, and only cheap kombu was made available there at the time; thus varied ways of cooking with kombu did not fully develop in that city. In Okinawa, however, kombu was used in cooking pork, leading to the creation of various new kombu dishes. These traditions are alive even today, and currently Okinawa prefecture has one of the highest consumption rates per capita of kombu.

Revival of Kombu

Since the end of World War II (1945), Western-style cooking has grown increasingly popular in Japanese households, with a steady and unmistakable movement away from the traditional Japanese-style diet. This trend was further driven by technological innovations during Japan’s rapid economic growth of the 1960s, which placed high priority on convenience. As instant seasonings became more available, more people preferred to use these, rather than making dashi stock from scratch. Blocks of dried bonito from which bonito flakes are shaved and large strips of dried kombu are much less common in Japanese households, but this is not to say they have disappeared completely: they are now available in convenient, pre-prepared forms.

With the advance of globalization in the twenty-first century, diverse cuisines come together in countries all over the world, and people have become quite discriminating about what they eat. Japanese cuisine, including Kyoto’s famous Kyo-ryori, is now popular worldwide. Developing alongside the internationalization of food has been the chemical analysis of ingredients. For some 800 years, the Japanese have cultivated an appreciation for umami. To seek the components of umami, Professor Kikunae Ikeda analyzed kombu and in 1907 discovered that they were to be found in the monosodium L-glutamate in kombu. This was the discovery of umami, which is now called the “fifth basic taste.”

Kombu, rich in umami, is now highly valued among chefs, and has won renewed recognition as a naturally healthy ingredient in home cooking. It is valued for its high levels of iodine, which helps produce thyroid hormones, and has been shown to help lower cholesterol and blood pressure. Japan’s kombu is deservedly prized not only by epicures, but by advocates of healthy eating.