The Many Paths of Soy Sauce

Our current Feature series traces Japan’s traditional food byways, and how various foods were originally transported and distributed throughout the country. In this final installment, we take a look at how soy sauce developed in Japan and traveled to the world.

by Masami Ishii

From East Asia to Japan

Soy sauce is an all-purpose seasoning, well suited for use in simmered, grilled and even uncooked dishes. This seasoning incorporates all five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter and umami. Its appealing rich, reddish-brown color and pleasant aroma enhance Japanese cuisine’s wide range of dishes. Japanese restaurants often refer to soy sauce as murasaki (literally, “purple”), a term that at one time carried connotations of cool and trendy.

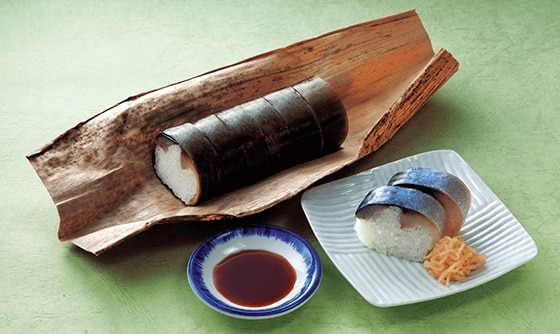

East Asia has a long tradition of preserving food ingredients in salt to make fermented seasonings; among these were kokubishio, made from grains such as rice and barley or beans. Japanese shoyu, or soy sauce, was refined and produced from that tradition. The origins of soy sauce arose when people began to use the liquid that accumulated on the surface of miso; subsequently, soy sauce production methods were developed. The first appearance of the term shoyu in a Japanese text can be found in the Bunmeibon Setsuyoshu, a Japanese-language dictionary written in the late fifteenth century.

From Kansai to Kanto

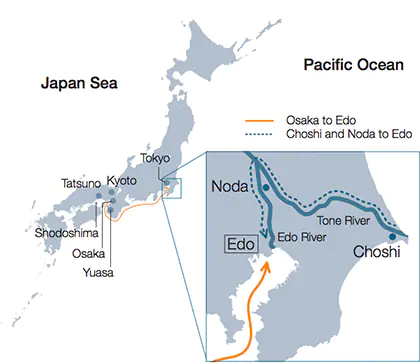

By the sixteenth century, soy sauce was manufactured throughout Kansai, the region that today includes Osaka, Hyogo and Wakayama. At that time, a dark variety of soy sauce called koikuchi was made, but in the latter half of the seventeenth century, a light color type was developed in the Tatsuno area of Hyogo Prefecture. This light color soy sauce was known as usukuchi, and was introduced in Kyoto: this is the soy sauce that contributed significantly to the development of the unique, refined flavors of Kyoto cuisine. It was only later in the early nineteenth century that Shodoshima, an island in the Inland Sea known for soy sauce production, shipped its first supplies of soy sauce to Osaka.

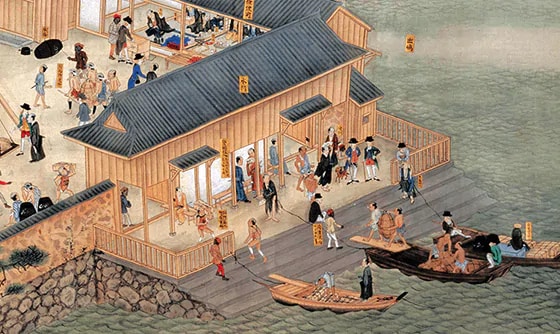

During the seventeenth century, soy sauce production, influenced by Kansai culture, began to make its way eastward toward the Kanto plain, the region surrounding Edo (now Tokyo). The Kansai area, which had more advanced manufacturing technology than Edo, produced much of the soy sauce at that time, and until the first half of the eighteenth century, soy sauce from the Kansai area was referred to as kudari-joyu—soy sauce that had been “shipped down” from Osaka to Edo on cargo ships called tarukaisen to accommodate the demand in Edo.

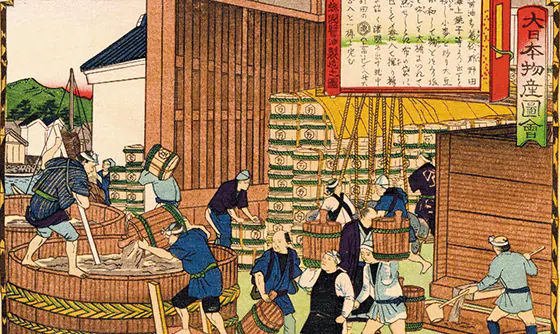

By the mid-eighteenth century, soy sauce makers in cities such as Choshi and Noda, located along Kanto’s Tone River, competed for a greater share of the market by utilizing the convenience of river transport. These two cities became major soy sauce production centers, and gradually Kanto came to surpass Kansai in soy sauce production.

From Traditional to Modern

At the onset of the twentieth century, soy sauce manufacturers in Noda, some 30 kilometers northeast of Tokyo, began to look beyond intuitive production methods based on experience, and started to introduce modern scientific brewing technologies. They planned to expand their marketing efforts with an eye on consumers in Tokyo, where the population was flourishing.

Soy sauce manufacturers in Noda quickly joined forces, and in 1917 they founded the Noda Shoyu Co., Ltd., the forerunner of Kikkoman Corporation. On a huge site of more than 132,000 square meters, they built 19 production plants, making possible the production of more than 36 million liters of soy sauce annually; this massive enterprise accounted for eight percent of all soy sauce made in Japan. Initially, the company produced a number of soy sauce brands, but the Kikkoman brand was considered to be of the highest quality, so the company eventually united all its brands under the single name “Kikkoman.”

From Japan to the World

In the early 1900s, Japanese soy sauce manufacturers expanded their markets overseas, but the largest of these was the U.S., where many Japanese had immigrated. The Second World War interrupted these efforts, but following the war, Kikkoman restarted shipping soy sauce overseas in 1949. A “teriyaki boom” took off in the U.S. and spread to other countries; overseas soy sauce production was to follow.

Kikkoman also began developing recipes to complement local foods. In order to bring about greater awareness of the taste of soy sauce, the company offered opportunities in supermarkets to sample food seasoned or prepared with soy sauce. This helped launch the use of soy sauce in local, traditional and new fusion cuisines. Since then, Japanese cuisine has become increasingly popular around the world, and the overall consumption of soy sauce continues to expand in overseas markets.

There is ongoing appreciation of the merits of Japanese soy sauce as a versatile seasoning, and various innovations have been introduced to meet the changing needs of consumers: for example, choices now include less sodium soy sauce products; smaller bottles, reflecting smaller family sizes; and even a special soy sauce containing dashi stock, which is convenient for cooking. Today, Kikkoman Soy Sauce in its many varieties is sold in over 100 countries around the world: it is a truly international seasoning.