Soba

Japanese cuisine includes many different types of noodles, each with its own history and traditions. In this third installment in our series about the diversity of Japanese noodles, we take a look at soba buckwheat noodles.

by Ayao Okumura

Soba, or buckwheat, originated in central Asia and was brought to Japan sometime between 1500-500 BCE. Rice grown in paddies became prevalent in Japan following this time, but soba continued to be cultivated mainly for food in impoverished rural areas, where rice could not be grown: poor farmers subsisted on soba and sold part of their harvest. Records dated 722 indicate that Japan’s emperor ordered soba to be cultivated as emergency food when there was a scanty rice harvest.

Early Soba Dishes

Soba was originally eaten either as a gruel called soba-gayu, made by boiling hulled soba in water, or as thick soba-zosui porridge, made by flavoring the gruel with miso. As well, hulled soba groats were pounded into flour with a mortar and pestle; the flour mixed with hot water was kneaded and made into soba-gaki. Sobagai-mochi cakes consisted of flour and water mixed then baked in the hot ashes of a brazier or open fireplace. Soba-gaki and sobagai-mochi were sometimes eaten with miso.

Records from 1480 suggest that a noodle-like form of soba first appeared among the Kyoto aristocracy, but the most definitive record which clearly indicates the appearance of soba noodles is dated 1574, mentioning soba as being made at the Joshoji temple, located in the Kiso district of the Shinshu region (present-day Nagano Prefecture). By the early seventeenth century, soba had been introduced in Edo (today’s Tokyo), and there it flourished as never before. One reason was its proximity to areas where soba was grown, which included the greater Edo area. Another was that, by the end of the seventeenth century, the population of Edo had risen to over one million, as samurai and their servants, tradesmen and others from throughout the country gathered to build the city and engage in commerce. The majority of these were single men for whom soba was prized as a fast food. The spread of waterwheel mill-ground flour and the availability of simple hand-turned stone mills also facilitated the production—and thus the consumption—of soba noodles.

Soba Styles

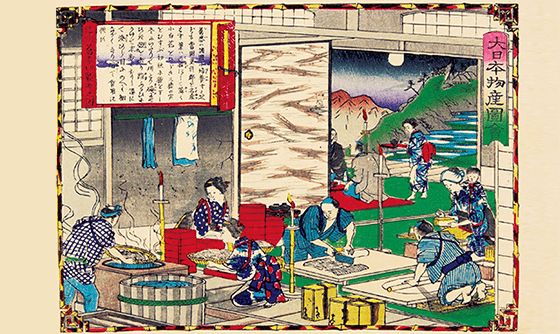

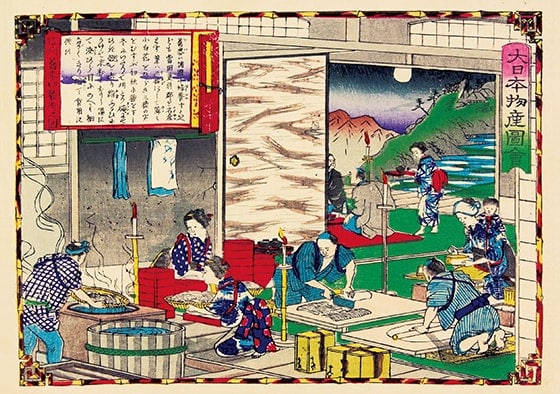

Soba noodles were served in basically three styles during the Edo period (1603-1867): the first was in restaurant-like shops where furnishings and serving utensils were carefully selected. The noodles were freshly made, cooked and served to patrons who were predominantly wealthy locals, members of the literati or those from the samurai class. The second was in tsuji-uri: these were shanty-like stalls that sold soba wherever people gathered—near temples, at river or canal docks and at construction sites. These stalls were stocked with dishes of pre-cooked soba noodles to which hot broth would be added upon ordering; the food was then eaten while standing. The third was in furi-uri, where peddlers sold soba from portable stands that were cleverly designed to hold drawers of pre-cooked soba, hot broth and a portable cook stove. Peddlers carried their stands from one place to another, hawking their noodles. Hailed by a customer, they set down their stall, placed the soba in a bowl and poured hot broth over it. Customers ate standing up in this case as well.

Soba Noodle Flours

The three basic kinds of soba noodles that are eaten today developed around the mid-1700s, according to how the flour was ground. Inaka soba (country-style soba) uses soba flour made from hulled soba, where the pellicle remains attached. This is a dark-colored but highly nutritious soba that was originally sold in shanty shops and by peddlers. Sarashina soba, the highest quality soba, is served at soba shops where the flour is made by refining the bran layer from the groats and grinding only the very center of the white inner part of the kernel. Nami soba (regular soba), the type most generally served in soba shops, is made from flour mixed with the remaining white inner part (not used in sarashina soba) and pellicle parts. Typically, 20 percent wheat flour is mixed with 80 percent soba flour to prevent the noodles from being crumbly in nature, as soba flour does not contain gluten. In some instances, however, the percentage of wheat flour is increased up to 40 percent, and occasionally grated yamato-imo (mountain yam) is mixed with the soba flour. Soba made of either 100 percent sarashina flour or nami flour is referred to as ki soba or jyu-wari soba—which literally means that the noodles consist of 100 percent soba flour; such noodles are served freshly made and freshly cooked, and are considered “gourmet” soba by connoisseurs. Another variation is cha soba, where ground green tea is added to the flour for fragrance and which imparts a light green color.

Varieties of Soba

Until the sixteenth century, basic soba sauce was a liquid made by adding katsuobushi dried bonito flakes to taremiso. Taremiso involved mixing miso with water, boiling it down and straining it. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it came to be replaced by dashi made from katsuobushi seasoned with tamari soy sauce and sake. From the late eighteenth century, basic soba sauce began to be made using katsuobushi dashi as a base with soy sauce and mirin, which produces the sweet savory flavor that is familiar today.

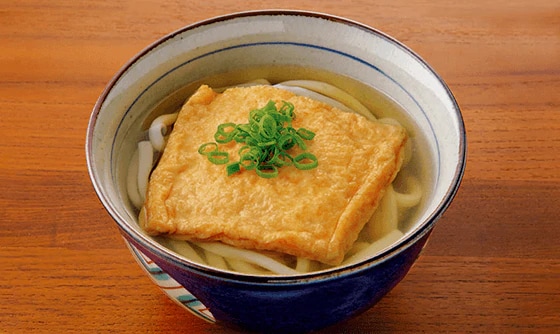

Then as now, ways of eating soba vary. Zaru soba is cooked and chilled, served on a bamboo mat called a zaru or a wooden steamer called a seiro. Each mouthful of noodles is dipped into a cool savory sauce. Contemporary variants of zaru soba include kamo-seiro soba accompanied by a warm dipping sauce containing morsels of kamo duck meat. Another is chilled hiyagake soba, served in a large bowl to which cool broth is added, accompanied by tempura or chopped long onion and other toppings. Kake soba or atsukake noodles are served in a hot broth, and tamago-toji soba is made by cooking a beaten egg into the broth. Kamo-namban soba is served in a broth cooked with duck meat and long onion. Arare soba is topped with small scallops, and hanamaki soba is topped with a generous helping of toasted and shredded nori seaweed—but the most popular soba with toppings is tempura soba, featuring two tempura shrimp.

The trendsetters of old Edo showed their true spirit in transforming a food once used to stave off starvation into something urbane and chic. Today, itinerant soba peddlers have disappeared, yet countless soba shops remain, and stand-up soba counters can be found in train stations and on street corners. All over Japan, one can hear the sound of people enjoying soba: to better savor the fragrance and flavor of the soba, it is essential to slurp one’s noodles.