Ramen

Our 2018 series on Japanese noodles has taken a wide-ranging look at the distinctive histories and traditions of somen, udon and soba. With this issue, we conclude with ramen, one of the country’s most popular noodles, which has fast become a global favorite.

by Ayao Okumura

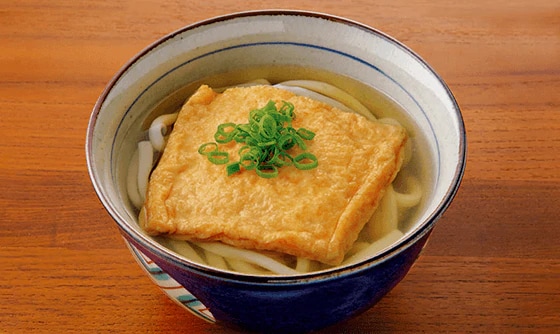

Ramen noodles are made by adding alkaline water to flour that has a protein content of 9 percent to 11.5 percent. Typically, ramen noodles are boiled, drained, added to a seasoned soup made from meat stock, and served with various toppings.

China Origins

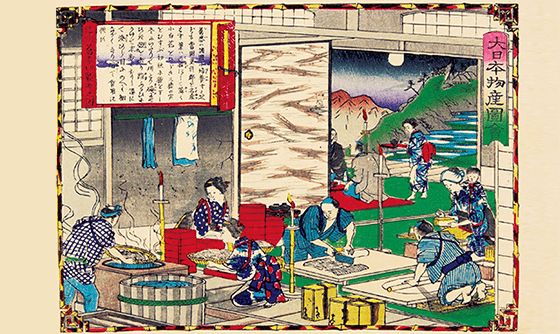

The roots of ramen can be traced back to China, whose noodle-eating food culture was introduced in Japan during the 1860s, when Japan ended its national isolation and reopened its ports to the outside world. The Chinese method of making and cooking noodles eventually evolved into a unique Japanese style that became known as “ramen.”

In the late nineteenth century, many Chinese settled in the port of Yokohama—some as shopkeepers, others as laborers and still others as housekeepers and chefs for Western traders who were active in the city. Eventually, those Chinese immigrants established their own Nankin-machi—Nankin being the Japanese pronunciation of Nanjing. Nankin-machi later evolved into Yokohama’s own unique Chinatown. In Nankin-machi, restaurants and food stalls popped up to cater to the needs of workers and shopkeepers; by 1887 there were about twenty Chinese restaurants in Yokohama which invariably served noodle dishes, including chashao tangmian soup noodles with sliced pork, and rousi tangmian soup noodles with thin pork strips. Not only Chinese, but Japanese locals patronized these shops, where the Japanese referred to noodle dishes as Nankin soba.

In 1910, a retired Japanese customs official who had been working in Yokohama opened his own Chinese restaurant in the Asakusa area of Tokyo. He hired Chinese cooks from Nankin-machi, changed the name of the noodle dishes from Nankin soba to Shina soba. He added toppings of chashao, or, as it eventually came to be called in Japanese, “chashu,” a type of cooked pork, and memma simmered strips of sweet bamboo shoots. Some years later, when the city of Tokyo was reduced to rubble in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, portable stalls serving Shina soba proliferated, and the popularity of the dish was assured.

Far to the north in Hokkaido, the Chinese restaurant Takeya opened in the city of Sapporo in 1921, across the street from a university. A Chinese chef at the restaurant concocted a delicious version of rousi tangmian that was authentically Chinese and much sought-after by Chinese exchange students studying at the university. Whenever a dish was ready, the cook would announce Hao le! (“a delicious dish is complete!”). That le sounded rather like ra to the Japanese ear, and it was from this phrase that ra was paired with the Japanese word men, meaning noodles. Takeya’s “ra-men” noodles became tremendously popular, setting in motion a fad that swept through the entire city of Sapporo.

Instant Fame

Courtesy of NISSIN FOODS HOLDINGS CO., LTD.

It was Momofuku Ando’s (1910-2007) invention in 1958 of the world’s first instant noodles—pre-cooked and dried ramen noodles sold in a packet—that spawned what would eventually become a global industry. At a time when television was just beginning to catch on in Japan, he aired instant noodle commercials constantly, familiarizing Japanese throughout the country with the product. In 1966, Ando traveled to the U.S. to pitch his instant noodles in supermarkets. Local supermarket staff removed the ramen noodles from the package, broke them in half and placed them in a paper cup, poured in hot water, and ate them with a fork. At that time, very few Americans owned noodle bowls or used chopsticks, and it was this episode that inspired Ando to develop new cup-type instant noodles. Today, some one hundred billion servings of instant noodles are consumed annually around the world.

Ultimate Ramen

Bowls of fresh ramen are enjoyed in countless restaurants and shops throughout Japan that vie to create the “ultimate” gourmet ramen recipe. They constantly experiment with combinations of soup flavor, noodle texture and various toppings. The noodles at such ramen shops usually consist of different types of high quality flour that has been skillfully blended. Ramen noodles vary in appearance: they can be thin, medium-thin or thick; some are straight, others curly. To make the noodles appear more appetizing, their yellow color is enhanced by adding kuchinashi gardenia colorant; but above all, it is the soup that is the most fascinating ingredient of ramen. Made with stock of primarily chicken or pork, Japanese cooks add kombu, katsuobushi dried bonito flakes, dried sardines or other dried fish, and dried shrimp or dried scallops, all of which release umami and greatly enhance the flavor. Some soups are made by simmering pork bones for days to produce a rich broth full of collagen and ash content. These robust soups are also popular with visitors from abroad, and some of Japan’s major ramen chain restaurants have branches in cities around the world.

There are three main ramen varieties, according to soup base: miso ramen, the miso-based soup of Hokkaido; shoyu ramen, the soy sauce-based Kanto-style found mainly around the Tokyo area; and tonkotsu ramen, the rich pork-bone salt-based soup popular in Kyushu. And throughout Japan, every locale offers up distinct ramen flavors: chashu cooked pork is a common topping, but regional versions of ramen often highlight a special local product, such as chicken, crab or shellfish. With Japan’s seemingly endless variety of unique ramen styles, one can experience and enjoy a truly “gourmet ramen” journey, all the way from northern Hokkaido down to southernmost Okinawa.