This new series explores the complexities of the deceptively simple plant-based Buddhist cuisine shojin ryori, beginning with its historical context.

Shojin ryori is Buddhist cuisine made entirely using plant-based foods. Cooks select their ingredients from among vegetables, edible wild plants, seaweeds and grains, while avoiding meat and fish products. How does shojin ryori differ from vegetarian food, one might ask? The origins of shojin ryori began in Buddhist temples, thus the cuisine itself is fundamentally characterized by religious elements.

Religious roots and practice

Buddhism, one of the world’s major religions, was founded about 2,500 years ago in ancient India by Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha, who drew up a list of precepts that believers were expected to follow as a guide to their faith. According to those precepts, which were intended to distance believers from desires related to possessions and wealth, those who pursued religious training were forbidden to engage in labor, which included cooking. In order to feed themselves, devotees practiced mendicancy, making the rounds of the homes of believers in Buddhism to receive offerings of food. It was a time of widespread turmoil with many wars and conflicts among small countries, and amid the strife, no one could be particular about what kind of food might be received. They ate whatever they were fortunate enough to be given. In those early days of Buddhism, therefore, the concept of shojin ryori did not exist. The custom of mendicancy is still practiced by some Buddhist groups in Southeast Asia even today.

Buddhism later spread to China, where it gained a widespread following and eventually split into various sects based on varying interpretations and policies regarding the original teachings. The number of followers who went through religious training greatly increased to the point that obtaining enough food by begging for alms proved infeasible; temples found it increasingly difficult to sustain themselves.

One of the sects, Zen, underwent a major change in its interpretation of the received doctrine. The doctrine had forbidden monks to engage in labor, but the Zen sect lifted this restriction by altering its own interpretation, wherein certain essential labors, such as cleaning, maintenance and field work, were referred to as samu (work/task), considered important forms of religious training. At the same time, zazen seated meditation was positioned as the center of that discipline training: monks were expected to follow the teachings of the Buddha with the body and the mind as a whole.

Allowing practitioners to gather food and cook whatever they wanted to eat, however, would have greatly diverged from the purpose of training intended to control human desires. The sect therefore developed its own rigorous rules of conduct, part of which prescribed the ingredients to be used for cooking and various instructions for preparing food. These instructions stipulated the appointment of a tenzo, or head of kitchen. Restrictions on ingredients extended to certain pungent vegetables; for example, garlic, Chinese chives, long onions and round onions were forbidden for causing bad breath and arousing unnecessary energies in the body. Thus the Zen sect came to regard cooking not simply as a daily chore, but as an important form of spiritual training—and this brought shojin ryori into being.

Shojin spirit

Even before the introduction of Buddhism here in the sixth century, Japan had a long tradition of purifying the mind and body through ablutions and simple eating. This purification, called kessai, derives from Shinto observances; food related to kessai is essentially vegetarian. The influence of Buddhist philosophy during the sixth-century Asuka period prompted Emperor Tenmu to issue a decree in 675 banning the consumption of meat. Surprisingly, that ban was upheld for about 1,200 years—at least, ostensibly—until early in the Meiji era (1868-1912). A vegetarian diet had become well-established among common people, resulting in a sort of secular shojin ryori. Their diet, however, should probably be more accurately described as “vegetarian food.” The meaning of shojin in Buddhism is to make an “effort” and “progress” in pursuit of the Buddha’s teachings. Food prepared or consumed without such commitment could not be labeled as shojin, even if it consisted of only plant-based ingredients.

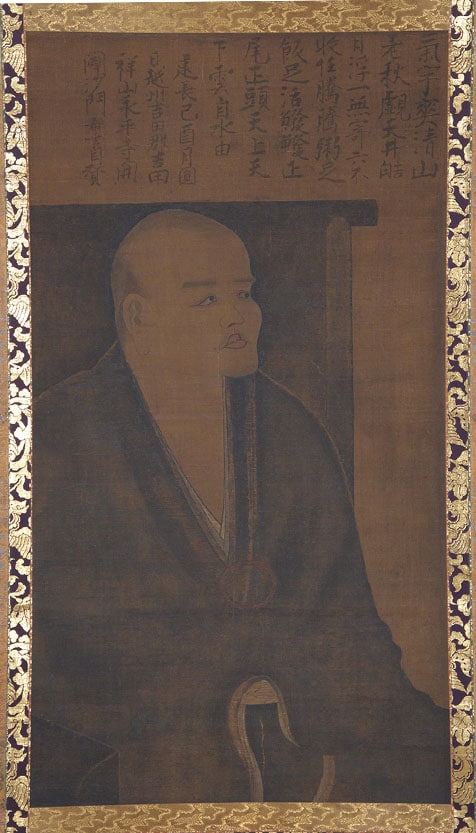

During the Kamakura period (1185-1333), the Japanese Zen master Dogen traveled to China and studied Zen Buddhism. He learned the essence of Zen through the role of tenzo, assuming responsibilities for food preparation as a form of religious training. Master Dogen later authored Tenzo Kyokun instructions for Zen cooking, which include important teachings on spiritual discipline acquired through cooking, as well as guidelines for food preparation. With this instruction, Zen temples in Japan became central to the steady development of shojin ryori.

Enterprises specialized in serving food and drink have to run a profitable business. Even in a household, there are many tasks to be performed, limiting the time that can be devoted to cooking alone. In the temples, however, monks in charge of preparing meals had no need to stint on the amount of time they spent trying new methods and developing new recipes, as this was perceived as spiritual training. They could lavish as much time and effort as they thought was needed. Thanks to this shojin spirit—an assiduous devotion to cuisine, no doubt enhanced by Japanese sensibilities and manual dexterity—they made improvements in cooking techniques and implements, and so developed a wide variety of shojin ryori recipes.

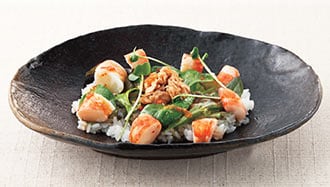

Preparation and presentation

Over long centuries of relative peace throughout Japan during the Edo period (1603-1867), various societal rituals became customary. For instance, during Buddhist memorial services for funerals or death anniversaries, after visiting the gravesite following sutra readings, participants partake of shojin ryori to commemorate the deceased. This tradition has become the norm, just as serving shojin ryori on tray tables used at such gatherings, and the menu itself, are now well-established. These customs were viewed as a means of offering solace to the deceased and were interpreted as what Buddhism considers part of training in Buddhist teachings, making the meal not simply “vegetarian,” but shojin ryori.

Today in Japan, Zen monks prepare shojin ryori every day in temple kitchens and dine in that style. Although there are limited opportunities for those outside this practice to dine on temple cuisine, it is still the custom to serve shojin ryori at memorial services, so almost everyone in Japan is familiar with this cuisine.

Shoshi Takanashi was born in 1972. Currently head priest at Soto Zen temple Eifukuji in Gunma Prefecture, he is also a specialist in shojin ryori and studies the spirit and techniques of this cuisine. From 2001-2005, he served at Daihonzan Eiheiji Tokyo Betsuin Chokokuji Temple, where he was tenzo (head of kitchen). His publications include Hajimete no Shojin Ryori: Kiso kara Manabu Yasai no Ryori (Beginner’s guide to shojin ryori: basics of vegetable cooking; 2013).