This second part in our series describes the complexities and commitment involved in making this traditional plant-based Buddhist cuisine.

Many people have the unfortunate impression that shojin ryori is rather bland. But on the contrary, in the hands of a well-trained and skillful chef, this cuisine is full of rich and robust flavors.

Natural taste

Shojin ryori is prepared using only plant-based ingredients such as vegetables, edible wild plants, seaweed products, grains and so on—in other words, no meat, fish or other animal ingredients are used. Inevitably, its flavors may not be as rich and strong if meat or fish were to be used, as plant- based elements naturally lean toward a lighter taste. When dining on shojin ryori, the true taste experience can be best appreciated if one does not compare it to the standards of ordinary fare. With shojin ryori, the natural taste of the ingredients themselves must be regarded as the standard for goodness. A carrot just pulled from the earth, for example, is extremely sweet. Rice is sweet. Do we really know the fresh taste of a just-picked cucumber, daikon or cob of corn?

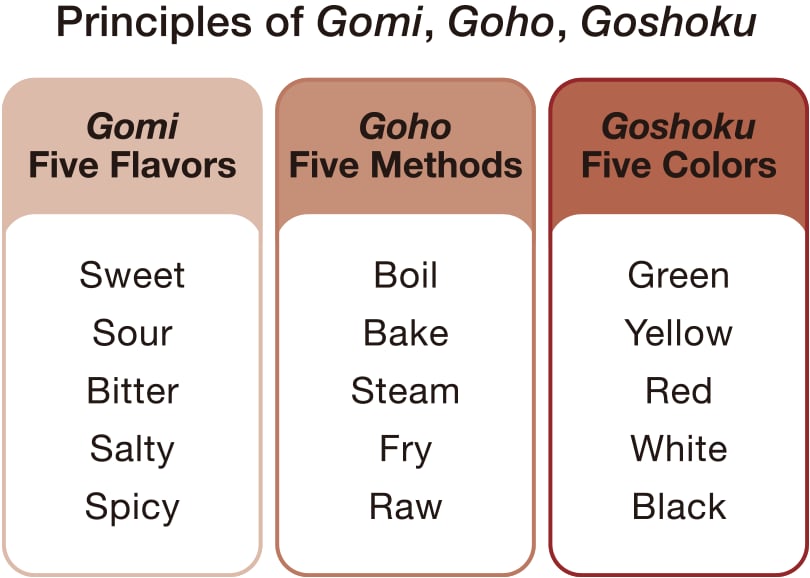

Shojin ryori does not employ strong seasonings or heavy sauces that may override the true flavors of individual ingredients. Rather, this cuisine focuses on extracting their distinctive and intrinsic flavors and seeks to communicate that essence. Flavor acquired in such a way is referred to as tan-mi; literally, “light flavor.” Tan-mi represents a kind of ideal concept that goes beyond the five basic flavors set out in principles of Japanese cuisine referred to as Gomi, Goho, Goshoku: Five Flavors, Five Methods, Five Colors (see diagram). Tan-mi is what seekers of enlightenment strive to achieve in their daily devotion to Zen precepts. Neither insipid nor lacking in flavor, the elusive notion of tan-mi goes beyond “light flavor”: it is the result of drawing out the essential quality of each ingredient.

Essential stock

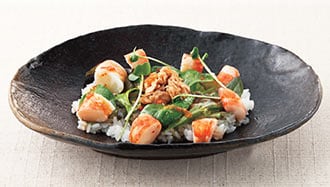

The fundamental procedure that is indispensable in eliciting that inherent nature is the creation of dashi stock. Soaking kombu and/or dried shiitake mushrooms in water overnight creates what is called ichiban-dashi, or “primary stock.” This is a clear liquid with a beautiful tawny tint and refined umami. It also has a pleasant aroma, so it is used for dishes such as clear soups and vinegared salads, where the flavor of the dashi can be savored directly. Niban-dashi, or “secondary stock,” is made by slowly simmering the same kombu/shiitake that was used in making the ichiban-dashi stock in a fresh pot of water. Umami-rich niban-dashi can be used in the preparation of dishes that possess comparatively stronger tastes; for example, foods prepared with oil, or recipes that involve the addition of miso or mustard. Just as when constructing the foundation of a building, if these two basic dashi stocks are not prepared well, they cannot draw out the flavors of the ingredients at their fullest strength. Therefore, properly prepared ichiban- and niban-dashi are essential when making shojin ryori. Using the dashi as the starting point, taste can then be adjusted using appropriate amounts of mirin, soy sauce and/or salt, whose respective umami elements interact to create flavors with depth that, although ostensibly simple, are quite complex.

Distinctive variations

Beyond the concepts and applications of flavor, as described above, the classic shojin ryori menu is predicated on the aforementioned principles of Gomi, Goho, Goshoku. Appropriate balance and combinations of these flavors, methods and colors are taken into consideration to prevent food from being bland and monotonous. Shojin ryori menus are carefully planned, based on these principles, so as to achieve distinct variations in combinations within each dish, within each course of the meal, every day.

Outside a Zen temple, one may notice a stone pillar carved with the words, “Stimulants and alcoholic drinks are prohibited within these premises.” “Stimulants” refers to pungent ingredients that unnecessarily arouse the energies of the body. These include, for example, Chinese chives, garlic, and long and round onions. Along with alcoholic drinks, such foods are unnecessary for those practicing Zen in temples, and are therefore not used in shojin ryori. (Sake that has been heated and dealcoholized may, however, be used in cooking.)

Spiritual process

Finally, the most important point in making shojin ryori is the spiritual mindset of the person who is cooking the cuisine. Shojin ryori is not about the creation of “fine taste” in a gourmet sense; one must not seek out a so-called gourmet food experience. If too much emphasis is placed on pursuing an elevated sense of taste or “deliciousness,” that notion then becomes an unattainable desire, which can descend into a form of greed: two concepts which, in Buddhist tradition, are believed to obstruct one’s path toward the right way of living and, ultimately, enlightenment.

What shojin ryori aspires to, rather, is a commitment to carefully and resourcefully bringing out the flavors of available ingredients in ways that result, quite simply, in good taste. In other words, the crucial difference between ordinary cooking and shojin ryori is the spiritual process experienced by the individual preparing the food, a process that involves focusing on the ingredients without distraction, rather than aiming for the fulfillment of any personal desires.

And so, while the resulting flavors may resemble those in “ordinary cooking,” what is significant is the spiritual experience that informs the preparation process. For the cook, recognition and acceptance of this distinction are what transform kitchen work into an integral element of shojin—part of one’s progress toward an understanding of Zen teachings.

Shoshi Takanashi was born in 1972. Currently head priest at Soto Zen temple Eifukuji in Gunma Prefecture, he is also a specialist in shojin ryori and studies the spirit and techniques of this cuisine. From 2001-2005, he served at Daihonzan Eiheiji Tokyo Betsuin Chokokuji Temple, where he was tenzo (head of kitchen). His publications include Hajimete no Shojin Ryori: Kiso kara Manabu Yasai no Ryori (Beginner’s guide to shojin ryori: basics of vegetable cooking; 2013).