Japan’s Mackerel Highway

Our 2013 Feature series traces Japan’s traditional food byways. In this first installment we follow the old route by which mackerel was conveyed inland from the coast.

by Masami Ishii

Mackerel Bay

Surrounded by oceans, Japan has always enjoyed the bounty of the sea. Today, thanks to transport technology for frozen and refrigerated foods, fresh fish are sold almost everywhere in Japan. However, in the days when goods were transported overland primarily by foot, it was not easy to sell fish in markets distant from the coast, and so it had to be preserved by salting or drying before being shipped inland.

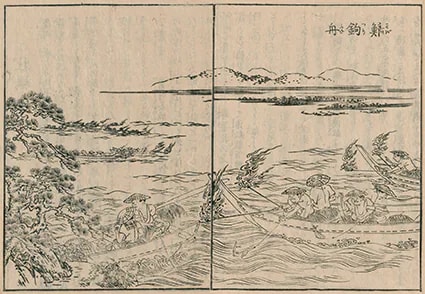

an illustration from the book Nihon-sankai-meisan-zue (1754).

Courtesy of National Diet Library digital archives

The happy outcome of these constraints, however, is the country’s extensive fish cuisine. Fukui prefecture’s Wakasa Bay is well known for the quantity and diversity of its seafood, which includes flounder and small sea bream; but it is especially known for its abundant mackerel, called saba in Japanese. Mackerel spoils relatively quickly, but is delicious either grilled or simmered, and has long been part of the popular diet.

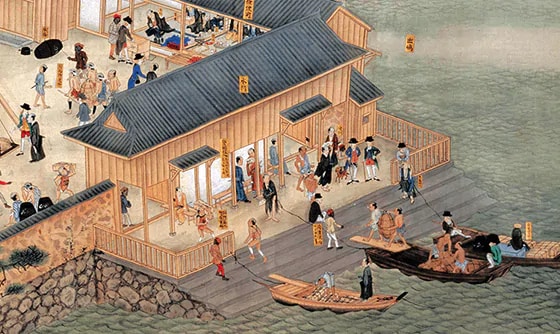

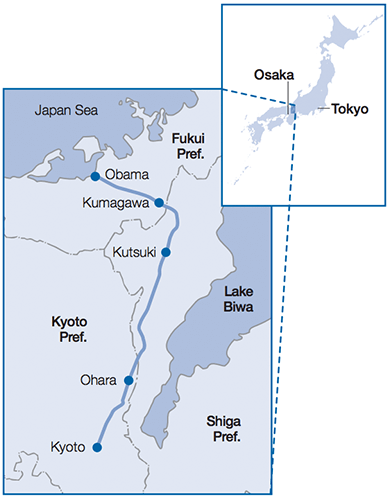

Fukui’s city of Obama, located at the head of Wakasa Bay, was a castle town during the Edo period (1603-1867) and has long prospered as one of the most important fishing ports on the Japan Sea. Mackerel caught in the waters of the sprawling bay would be brought to the docks early in the morning and lightly salted, then immediately shipped off to Kyoto, some 70 kilometers away. A number of routes led to what was then the capital, but the primary route was the Wakasa highway, which went from Obama through the villages of Kumagawa, Kutsuki and Ohara, before arriving at the imperial capital.

Journey to Kyoto

Until railways were established in the early twentieth century, goods were carried by foot in loads of 40-60 kilograms by highway carriers known as kaido-kasegi. This was hard work, but relatively lucrative, since all one needed was stamina and a length of rope to tie up one’s load. Over the centuries, the Wakasa highway route came to be known as the “Mackerel Highway” (saba kaido). By the time the carrier would reach Kyoto a day and night after leaving Obama, the salt would have penetrated the mackerel to just the right degree; or in scientific terms, the salt would have reacted with the protein of the fish to produce amino acids, producing a fine taste of umami.

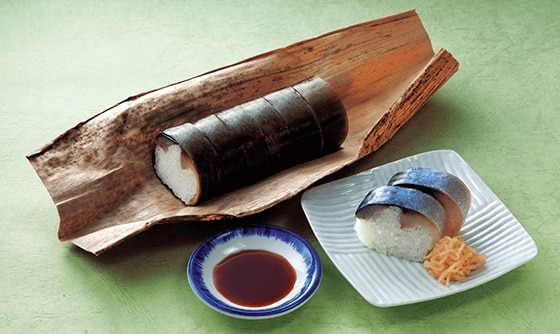

At the end of its journey, the mackerel was rinsed sparingly to remove salt and marinated in vinegar to produce what is famous today as saba-sushi. This is the history that lies behind the numerous shops in Kyoto known for their mackerel sushi. Saba-sushi is especially good in the spring, when the mackerel is rich in fat. Saba-sushi came to be part of the festive fare traditionally eaten during the city’s Aoi Festival, celebrated May 15. In due course, saba-sushi shifted from a quite ordinary dish to a luxury dish eaten only on special occasions.

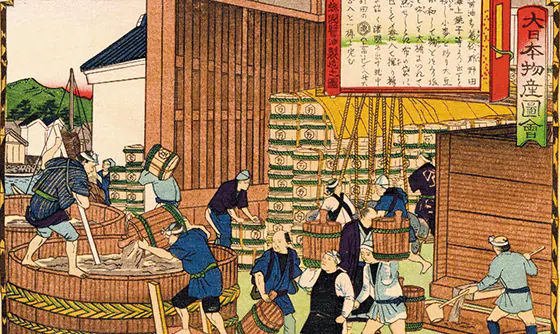

The Wakasako, a record written in the mid-eighteenth century by a local merchant named Itaya Ichisuke, depicts a sense of what those times must have been like. When mackerel fishing was at its height in the Wakasa region, the account says, a single fisherman could hook 200 fish in a night. During the O-Bon summer festival, which honors ancestral spirits, it became customary to present split-open, salted mackerel (sashi-saba) as gifts, thus fueling a lucrative market. Salted mackerel were shipped to the Kanto (Tokyo plateau) area as well, and so a huge amount was processed for market. The record also tells us that, while Wakasa was well known for its dried flounder, it was mackerel to which it owed its prosperity.

The Heritage of the Highway

Today, mackerel sushi and the heritage of the “Mackerel Highway” are again playing a role in the economic prosperity of Obama and nearby towns. A special plaque has been affixed in the street of a local shopping district in Obama that marks the beginning of the famous highway, while the nearby Mackerel Highway Museum exhibits photographs, pictures and artifacts recalling its heyday. The Miketsukuni Wakasa Obama Food Culture Museum, located on the coast, features interactive exhibits where visitors learn about the history of Obama’s food culture.

In Kumagawa, a stopover on the Mackerel Highway, the former Kumagawa Village Office was renovated to house the Wakasa Mackerel Highway Kumagawa-juku Museum as a monument to the time when the town prospered as a major post-town along the highway. Every house once made saba-sushi in large quantities for special occasions and during the New Year. Today, preservation techniques have improved and nowadays a lighter flavor is preferred, using less vinegar. Even though time-honored recipes are being passed on, it is becoming more difficult to perpetuate the traditional flavors.

Grilled saba-sushi (yaki saba-sushi), grilled mackerel on sushi rice, is now popular. The people of Obama recommend that the sushi container be kept upside down, so that oil from the fish does not seep into the rice. Grilled saba-sushi is also sold at gift shops in Tokyo airports, and is served on planes. Today, some vacuum-packed mackerel products are made with mackerel from Norway, since the local catch may not always be as abundant as it once was. Perhaps now, a new “Mackerel Highway” for the global age is in the process of being created.

Masami Ishii was born in 1958. He graduated from Tokyo Gakugei University in 1980 from which he later received his Masters degree in Japanese language education in 1984. Prof. Ishii specializes in Japanese literature and folklore, and he has been teaching at Tokyo Gakugei University since 1993. He has authored many books and publications such as Tono Monogatari-e-no-Goshotai (An Introduction to Tales of Tono) and Mukashi-banashi-to-Kanko—Kataribe-no-Shozo (Folktales and Travel—a portrait of a storyteller).