Somen

Noodles are one of Japan’s most popular foods, and Japanese cuisine is renowned for its diverse types of noodles, each with its own complex heritage and unique traditions. In this new series, Food Forum takes a closer look at the delicious world of Japanese noodles, beginning with somen.

by Ayao Okumura

Sakubei

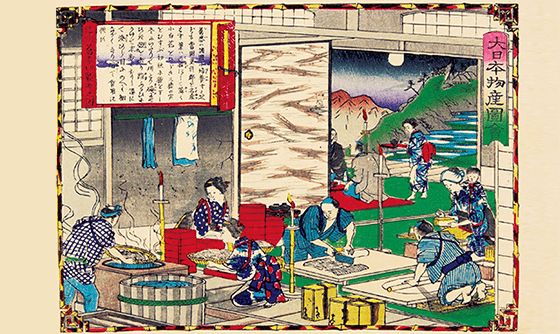

Wheat was introduced from China to Japan via the Korean peninsula some 2,000 years ago, yet it was not cultivated on a substantial scale here until about 1,300 years ago. In contrast to the hard wheat strains from which Italian pastas are derived, so-called soft wheat arrived in Japan in the Nara period (710- 794). At that time, the method for making wheat-flour noodles was introduced in Nara, then capital of Japan. These noodles, called sakubei, were made by kneading wheat flour with salted water into a dough, which was then broken up into small pieces. These were rolled out between the palms of the hands and covered with starch to facilitate stretching into very long, fine strands using a pair of bamboo sticks. After stretching them in this fashion, they were hung outside to dry.

an ancient dish as reproduced by Dr. Okumura

Sold at markets, sakubei was available to ordinary people, and was also among goods distributed to workers engaged in the state-supported task of copying Buddhist sutras from China. There were two ways to eat sakubei. One was to rinse the boiled noodles in cold water and garnish them with crushed walnuts and ginger, accompanied by a sauce made of either miso and vinegar, or of vinegar and jiang. Jiang, a precursor to today’s soy sauce, is the liquid drained from fermented soybeans. The other way was to enjoy sakubei as a kind of dessert, where the boiled noodles were eaten with boiled adzuki beans sweetened with mizuame glucose syrup made from fermented glutinous rice.

During the star festival of Tanabata, celebrated on the seventh day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, typical offerings included uri melon, eggplant and sakubei. By presenting offerings of sakubei noodles, with their long, thread-like shape, women prayed for sewing skills, along with a bountiful summer harvest. Dining on the long noodles was a way of praying for long life. One reason behind this custom may be that during summer, rice—already a staple in the diet—was likely in short supply.

Thinner and Longer

Somen emerged as an advanced form of sakubei in Song dynasty China (960-1279). Instead of starch, vegetable oil was used to prevent the surface of the noodles from drying out, allowing them to be slowly and gradually stretched even longer, to diameters of less than 1.7 millimeters, or 0.07 inches—a process which took two days. This method of making somen was introduced to Japan sometime in the early thirteenth century. We know that by the early sixteenth century, this exacting technique was being demonstrated to customers in Kyoto.

The manner in which Japan’s early somen was eaten differed from that of the earlier sakubei noodles. During the summer months, the boiled noodles were rinsed in cold water, and each mouthful was dipped in a cold clear sauce called taremiso, made by mixing miso with water, boiling it down and then straining it through a cloth. Chopped green onion and ground mustard paste were additional condiments. This way of eating somen was distinctive to Japan. In winter, somen was often eaten warm, simmered in miso soup; another way was to add the noodles to a bowl of hot water, and dip them in cool taremiso before eating.

In the eighteenth century, somen was produced throughout Japan in more than thirty noodle-producing areas; at this time, the noodles began to be cut into lengths of 18 centimeters, or about 7 inches—convenient for eating—and were sold in bundles of what is now about 100 grams (3.5 oz.). Somen that had been stored and matured for two or three years was prized as being silky and smooth, and thus more pleasurable to eat. This is because of changes in the proteins, which eliminated stickiness and made the noodles easier to swallow—the only problem was that oxidation of the vegetable oil left a rancid smell.

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, tasty dipping sauces made with soy sauce, mirin* and katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes) dashi became available, which greatly enhanced the pleasures of eating somen. Eventually, the custom of exchanging Ochugen summer gifts of somen developed. In those days, a Chinese-style dish called taimen (sea bream somen) was enjoyed in Nagasaki Prefecture. A sea bream would be cut in half, deep-fried, and then simmered in katsuobushi dashi and soy sauce, to which cooked somen was added. This dish became popular among villages along the shores of the Inland Sea, and its preparation was gradually modified to involve simmering the sea bream in water with soy sauce; somen was boiled, then rinsed and cooled, and seasoned with this sea bream broth before being served with the sea bream on a large platter. This special dish is still presented at weddings, as it evokes the homophone taimen, which means “meeting,” referencing the meeting of the two families of the bride and groom.

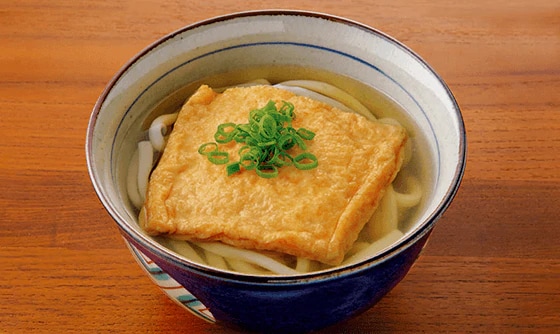

Somen Today

Almost all somen today is manufactured by machine. It is a favorite summer dish often eaten simply dipped in a soy sauce and dashi-based sauce, together with condiments such as chopped green onion and grated ginger. However, ways of eating somen differ by region. In northern Aomori Prefecture, for example, it is served in cooled broth made from simmered sazae horned turban shell, topped with slices of sazae and uni raw sea urchin. In Aichi Prefecture, in a town at the tip of a peninsula south of Nagoya, somen is served with hishigani elbow crab. Along the coast of the Inland Sea in Hiroshima Prefecture, somen is cooked in the broth of simmered kuro-mebaru rockfish. In landlocked villages of northern Shiga Prefecture, a festive summer dish involves somen served in broth flavored with grilled mackerel, eaten with the mackerel. In the Amami Oshima Islands in Kagoshima Prefecture, south of Kyushu, somen is cooked in a soup made from salted pigs’ feet. In subtropical Okinawa Prefecture, the noodles are boiled, drained and then pan-fried with canned tuna or corned beef.

- *Made of glutinous rice, rice koji and shochu distilled liquor. Originally a beverage, mirin began to be used as a seasoning at this time.

Ayao Okumura, Ph.D. was born in 1937 in Wakayama Prefecture. A former professor at Kobe Yamate University, Dr. Okumura is a specialist in traditional Japanese cuisine. He is currently part-time professor at Osaka City University Graduate School, lecturing on the establishment and structure of Japanese food culture; as owner of cooking studio Douraku-tei, he is known for his authentic reproductions of historic Japanese dishes and menus. His various publications include Nippon men shokubunka no 1,300 nen (“1,300 years of Japanese noodle food culture,” 2009; revised 2014).