Udon

There are a variety of noodles to be discovered in Japanese cuisine, and each type has its own distinctive history and characteristics. In this second installment in our series on the world of Japanese noodles, Food Forum introduces udon wheat noodles.

by Ayao Okumura

Previously we presented somen noodles, traditionally made by hand-stretching. Udon noodles, by contrast, are usually knife-cut. Like somen, udon is made by kneading wheat flour with salted water into a dough; this is then rolled out into a sheet with a long wooden rolling pin to a thickness of only three to four millimeters, about 0.15 inch. The sheet is folded to a width of some 15 centimeters, or about six inches, then cut into three to four millimeter-wide strips of noodles with a large cleaver-like blade called an udon-kiri. Today, the udon-making process is predominantly automated, yet many restaurants in Japan still make it by hand. There are many forms of udon: it is available fresh-made, pre-cooked, frozen and dried, and it varies in width.

Eating Udon

The origins of udon in Japan date back to knife-cut noodles introduced from China in the early 1200s; these were about two millimeters (0.08 in.) wide and were called kirimugi, “cut wheat.” Kirimugi noodles were usually boiled, rinsed and cooled, then eaten by dipping in a cold clear sauce called taremiso, made by mixing miso with water, boiling it down and then straining it through a cloth. That dipping sauce eventually came to be made with a dashi broth of katsuobushi dried bonito flakes and soy sauce; noodles dipped in this sauce were called hiyamugi, and were garnished with either chopped green or long onion and a touch of ground mustard paste.

The manner of eating hot boiled udon noodles arose in a Zen temple in Kyoto during the early 1300s. These noodles were cut wider than hiyamugi so as not to become too soft in the hot water. Later, in the early 1600s, people began to pour a hot savory soup over their boiled udon. This soup consisted of dashi made from katsuobushi seasoned with either the taremiso or with what was at that time expensive tamari soy sauce. By the late eighteenth century, however, ordinary soy sauce was used in the soup.

Soup and Toppings

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, udon became a popular fast food in the city of Osaka, then the commercial center of the country. Noodle makers there have long mixed both local and regional Japanese wheat to make special udon flour, but what has always distinguished udon in Osaka is its delicious soup. The secret lies in the strong umami of its dashi, made of a complex blend of high quality kombu from Hokkaido and katsuobushi, along with other dried fish flakes such as mackerel and mejika, a species of bonito. This combination of kombu’s glutamic acid with the inosinic acid element of the dried fish flakes increases the overall umami of the soup by seven or eight times, compared to dashi made with kombu or katsuobushi alone. Seasoning this umami-rich broth with usukuchi light color soy sauce, plus a small amount of mirin, produces a very elegant soup which makes the udon noodles taste even better.

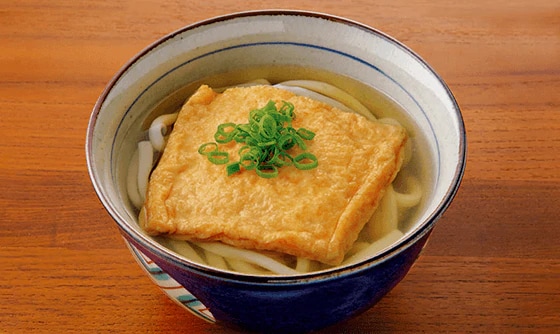

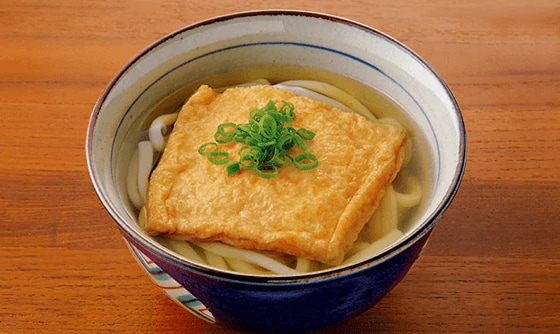

In Osaka, udon has evolved over the years, resulting in a variety of recipes. Tamago-toji udon is similar to egg-drop soup, and is garnished with chopped green onion. Similar to this is savory steamed egg custard with boiled udon, called odamaki-mushi. Traditionally, this involves pouring beaten eggs mixed with dashi six times the amount of egg over a bowl of udon and other ingredients and steaming it. Kitsune udon with abura-age deep-fried tofu seasoned with soy sauce, sugar and dashi is an Osaka specialty. Other popular dishes include udon topped with beef or covered in curry. Udon topped with sliced tamago-yaki rolled omelet, sweet simmered shiitake mushrooms, slices of kamaboko fish cake and chopped green onion is another variation. There is also an udon dish where the broth is thickened with kudzu starch.

Udon Hot Pot

During the 1850s, nabe-yaki udon was served from itinerant stalls in Osaka. Udon noodles and assorted ingredients were cooked with dashi broth in shallow single-serving iron pots over a charcoal stove. These days, restaurants serve nabe-yaki udon in lidded earthenware pots, with more extravagant toppings than in the past, such as shrimp tempura, chicken, grilled anago conger eel, sweet simmered shiitake mushrooms and kamaboko. At one particular restaurant in Osaka, cooked rice is added to the pot along with the noodles.

Udon-suki evolved as a sort of family-style version of nabe-yaki udon. It is generally eaten with several people serving themselves from a large shallow pot that is heated up right on the table, on a portable cooking element. After the soup is warmed, ingredients like shrimp, chicken, grilled anago, deep-fried tofu dumplings, nama-fu (wheat gluten), yuba tofu skin, vegetables and various mushrooms are added, followed by pre-cooked udon noodles, resulting in a nutritionally well-balanced meal.

Regional Variations

Udon is enjoyed throughout Japan, but its cooking styles and soup flavors tend to differ by region. In general, the soup is lighter in color in the western part of the country and darker in the east and north. Distinctive to the Nagoya area in western Aichi Prefecture is miso-nikomi udon, served in a thick soup made with Hatcho miso fermented from locally grown soybeans, to which chicken and egg are added. It is served bubbling hot in an earthenware pot.

On the island of Shikoku, Kagawa Prefecture is famous for Sanuki udon, which is such a staple there that people even eat it for breakfast. Kama-age udon is traditionally eaten straight out of the hot water in which it is boiled, simply dipped in a sauce seasoned with soy sauce. One quick dish is hot kama-tama udon, mixed in a bowl with raw egg and soy sauce. Grated daikon radish and soy sauce alone are enough to make a fine complement to chilled udon. Particularly popular in Kagawa Prefecture are self-serve shops, where diners can select toppings for themselves from assorted ingredients, such as tempura, to add to their bowl of freshly boiled udon.