This year's Food Forum feature series takes up the topic of sushi, one of the most globally popular Japanese foods.

Many different kinds of sushi have emerged throughout its long history, but perhaps what most commonly comes to mind today is the image of nigiri-style sushi called nigiri-zushi,* a hand-pressed sushi made with a bite-sized portion of sushi rice topped with raw seafood. Although nigiri-zushi was developed in Japan, the invention of sushi itself did not take place here.

Sushi origins

Sushi likely emerged from southern China or Southeast Asia centuries ago. Freshwater fish inhabiting rice paddies was used to make the earliest type of sushi called nare-zushi, salted fish which was then pickled in a wooden barrel packed with cooked rice. The rice used to make nare-zushi was not mixed with vinegar; rather, it was allowed to ferment over the course of several months to half a year, thus souring the fish and imparting it with an acidic flavor. The fully fermented salted fish resulting from this process was called hon-nare. Only the fish was eaten, while the rice, broken down to liquid form, was discarded. What we consider to be the precursor of sushi, therefore, was originally a preserved fish, rather than the food we know today that features fresh seafood and rice.

It is unknown precisely when nare-zushi was first introduced to Japan, but the written kanji characters for sushi appear in Japanese documents dating from around the mid-eighth century. At the very least, it can be assumed that, prior to that time, some form of sushi would have existed in Japan. Rice cultivation spread widely in Japan during the Yayoi period (400 BCE-300 CE), and given that sushi at this time was made with fermented rice, sushi is therefore believed to have been produced from the Yayoi era onward. Early tenth-century records refer to different types of nare-zushi; namely, funa-zushi in Shiga Prefecture made with funa crucian carp, and ayu-zushi in Gifu Prefecture made with ayu sweetfish—both of which are still made today.

“Faster” sushi

From this point, sushi proceeded to evolve and undergo numerous changes. References to nama-narezushi, called nama-nare for short, appear around the fifteenth century. Nama means raw in Japanese, and nama-nare refers to partially fermented fish: in this case, fermentation time was reduced to one or two months, and the rice used to ferment the fish, previously discarded in making fully fermented hon-nare, was consumed along with the fish. Today, most fermented sushi in Japan is a type of nama-nare. Given its abbreviated preparation time, nama-nare ultimately contributed to the broader dissemination of sushi—yet people wanted to speed up this fermentation process even further. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, fermentation-accelerator was added during the process: some added koji mold (primarily Aspergillus oryzae), and even today there are many kinds of sushi made using koji.

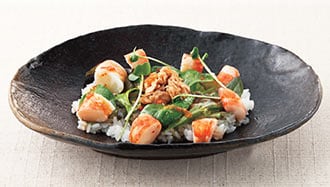

Others added sake or vinegar to accelerate the process. Vinegar was first used merely as a supplemental agent to fortify the distinctive acidic flavor rather quickly—a flavor usually generated through the process of slow fermentation. During the eighteenth century, however, vinegar gradually became the primary source used to create this characteristic sourness, thus reducing the time required for fermentation. By the early nineteenth century, inspired by this flavorful use of vinegar, and by accelerating the overall sushi-making process, nonfermented sushi had emerged. Rather than fermenting the fish, the rice itself was made slightly acidic by mixing in vinegar, creating the combination of vinegared rice topped with seafood that we know today. This was referred to as hayazushi, or “fast-made sushi.” Many contemporary types of sushi arose during the nineteenth century, among them hako-zushi “box-pressed sushi,” chirashi-zushi “scattered sushi” and maki-zushi “rolled sushi.”

It was finally in the 1820s that the prototype of today’s familiar nigiri-zushi appeared. Originally, the rice was not topped with raw fish ingredients; rather, the fish used for sushi (referred to as sushi-dane) was marinated in salt, vinegar or soy sauce or it was boiled or grilled to prevent spoiling. This sushi was rather sizeable, to the point where just three nigiri-zushi would be considered a filling meal. During the Edo period (1603-1867), itinerant stalls in the streets of Edo (Tokyo) sold this sushi as a snack or light meal.

Nigiri sushi

In the lean days following the Second World War, food—particularly rice—was scarce, thus an ordinance was passed in 1947 prohibiting the unrestricted sale of rice and other rice-related items on restaurant menus. Sushi shops found a work-around by obtaining business permits as so-called food-processing contractors: for every cup of rice that customers themselves would bring in, the business agreed to make just ten pieces of sushi. This idea, devised by Tokyo sushi chefs, quickly spread throughout the country and became the overwhelming standard. Another postwar shift was the remarkable development in refrigeration technology, which led to the widespread use of raw fish as sushi-dane. The practice of dipping sushi in soy sauce before eating became normalized around this time.

During Japan’s rapid economic growth in the 1960s and 1970s, nigiri made at sushi shops experienced a heyday. Upmarket and costly, nigiri assumed a prestigious and exalted role in the world of Japanese cuisine. Conversely, overshadowed by this formidable reputation, the homemade sushi that people had formerly made on a daily basis or as a festive dish on special occasions began to experience a slow decline. It was not until the 1970s that the price of nigiri-zushi fell as shops began to offer takeout and kaiten-zushi conveyorbelt sushi, which became particularly popular with families and children.

Sushi diversity

Reflecting on over 1,200 years of sushi history, it is striking to note that this dish has evolved from being a means of preserving fish over long periods of time, to being among the least preservable foods available today. Nigiri served in a sushi shop must be eaten immediately to appreciate it at its best. Many different varieties of sushi, each reflecting various locales and regions, are still made in Japan today, albeit less frequently; indeed, even nigiri-zushi can be enjoyed on different levels, from reasonably priced versions to expensive gourmet servings. Perhaps it is these diverse types of sushi that sustain the exclusive image of nigiri-zushi even today.

- * The pronunciation of “sushi” changes to “zushi” when a specific name or style is placed before the word “sushi.”

Terutoshi Hibino was born in 1960 in Gifu Prefecture. He received his BA and MA degrees from Nagoya University, and his PhD in Japanese Culture from Aichi University. He is currently professor at Aichi Shukutoku University and honorary chairman of the Shimizu Sushi Museum (Shizuoka). His publications include Sushi no Kao (Portraits of sushi; 1997); Sushi no Rekishi o Tazuneru (Following the history of sushi; 1999); and Sushi no Jiten (Encyclopedia of sushi; 2015).