In this final installment in our series on sushi, we look at the development of the contemporary identities of sushi, both in Japan and globally.

From the latter half of the 1950s into the early 1970s, Japan was in the throes of rapid economic growth. During this time, sushi came to be considered an “ultra-luxury food,” and its high prices reflected this perception. Some sushi chefs were renowned for using very select ingredients, while the interior decor of many high-end sushi restaurants conveyed elegance and sophistication. The numbers of such places gradually fell as Japan’s economy flattened, but the idea had been planted that sushi was a food to be enjoyed on very special occasions.

Price and accessibility

During those decades, however, sushi prices concurrently began to fall. One factor was the emergence of stores specialized in take-home sushi. Many take-out stores were established as part of larger chain stores selling prepackaged sushi: these adopted a “central kitchen” business model, wherein preliminary ingredient preparation is performed at a centralized facility and follow-up processes of cooking, packaging and sales are handled by individual affiliated stores. Centralized mass production and streamlined operations made it possible toprovide sushi at lower prices.

The advent of kaitenzushi conveyor belt sushi also led to lower prices and broader accessibility. The first kaitenzushi shop had appeared in 1958, but not until the 1970 Osaka Expo did the concept become widely known—and its spread throughout the country was a 1980s phenomenon. The kaitenzushi concept shocked conventional sushi shops, as it introduced a completely innovative serving style. Rather than making individually requested sushi at the counter on the spot, kaitenzushi is pre-made and set out on small plates that are carried around the counter on a conveyor belt, tempting diners to pick them up as they wish. Prices for sushi were often indicated as being “at market price,” without a clear listing on the menu, but kaitenzushi clearly indicates a set price per plate. Moreover, the sight of the conveyor bearing tantalizing dishes is especially entertaining for youngsters, making affordable kaitenzushi very popular with families. Kaitenzushi essentially automated the sushi counter business: today, the number of these shops continues to grow, not only in Japan, but globally.

Acceptance overseas

It took a considerably longer time for sushi to be generally accepted in overseas markets. In the United States, for example, the notion of eating raw fish was once considered “uncivilized,” with no possibility of accepting something like sushi. During the 1980s, more people became health-conscious and came to appreciate the healthy, low-fat Japanese diet. In the 1990s, globalization triggered a more nuanced perception of Japanese foods as being chic and trendy, especially in the world’s major cities. Sushi was first embraced by well-off diners and foodies before attracting the attention of the general public. On the heels of the now globally popular Japanese anime and manga subculture, interest in Japanese cuisine continues to grow apace, and sushi has come to be embraced by the broader strata of society. Today there is considerable attraction—not only in sushi itself—but in sitting at a counter across from a sushi chef and engaging in casual conversation. The notion of a special relationship between chef and customer, of eating sushi made specifically to one’s individual taste, has come to hold great appeal. Sushi shops introduced the format of close communication between chef and customer that was previously unknown in Western restaurants.

Appealing imports

There are many long-established sushi shops in Japan focused on upholding tradition, and which are reluctant to change—particularly those that have been passed down over a number of generations. Yet overseas sushi establishments have introduced some surprising culinary innovations. Hand-rolled temaki-zushi, for example, was once made only for kitchen staff behind the scenes in Japan as a meal, but overseas sushi chefs judged its flexible format ideal to try out unconventional sushi ingredients suitable for local palates. The now-ubiquitous California roll, formed with white rice on the outside and nori seaweed inside, was created in response to a sense that the black color of nori-wrapped sushi was unappealing to non-Japanese diners, and California rolls are sometimes sprinkled with bright orange tobiko flying fish roe for a dash of color and flavor. Newly created sushi concepts like the California roll and novel temaki-zushi combinations were later exported to Japan and popularly adopted; moreover, such inventive, offbeat rethinking of how sushi can be prepared has contributed to attracting new fans around the world.

Another sushi style that has grown out of imports is the popularity of salmon nigiri-zushi, an ongoing hit in kaitenzushi shops. Salmon was once shunned as a sushi ingredient in Japan, as locally sourced fish was believed to carry parasites. When it was found that Scandinavian salmon was uncontaminated, imports surged and fueled the tremendous popularity of salmon sushi, not only as kaitenzushi, but in regular sushi shops and take-outs.

Individual style

During Japan’s rapid economic growth in the 1960s and 1970s, many sushi dishes once prepared at home virtually vanished, replaced by low-cost store-bought nigiri-zushi. In this time when it was common for people to work long hours, many seem to have concluded that, rather than painstakingly make home-made sushi from scratch,packs of reasonably priced pre-made sushi were good enough to satisfy one’s cravings.

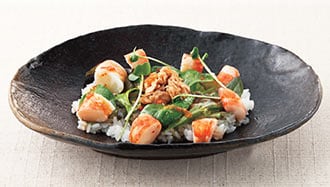

Recently, however, in light of society’s changing attitudes on life-work balance, even busy employees are spending more time at home, and the number of those challenging themselves to make their own homes-tyle sushi has increased. They may not attempt the kind of nigiri-zushi made by a professional, but tend to opt for making maki-zushi rolls, chirashi-zushi “scattered sushi” or pressed hako-zushi for a meal or special event, sometimes livened up with unique garnishes.

Another product of the times is the decorative futomaki-zushi thick sushi roll. These large rolls incorporate original artistic designs such as flowers and patterns which are only revealed when the roll is sliced. Decorative futomaki originated as a local family tradition in Chiba Prefecture, where recipe competitions are held each year. The trend of making these creative rolls has spread across Japan, thanks to recipe books, social media and hands-on workshops.

Inari-zushi thin deep-fried tofu pouches filled with sushi rice is easy to make and decorate with innovative garnishes. Gourmet fairs around Japan feature inventive, locally made inari-zushi and invite children to create their own using favorite ingredients like cheese, ham, nori and more. Events like these allow people to individualize and enjoy sushi without complicated preparation or equipment.

Sushi has evolved over time amid considerable social change and continues to do so. From its image as a high-end gourmet counter experience to the current mass-market accessibility of kaitenzushi, today’s sushi has gone definitively mainstream. Sushi prepared at home has also experienced transformations, from what are considered classic recipes to new, individualized forms with tempting, creative embellishments. The world of sushi has expanded and diversified, and its popularity shows no sign of waning.

Terutoshi Hibino was born in 1960 in Gifu Prefecture. He received his BA and MA degrees from Nagoya University, and his PhD in Japanese Culture from Aichi University. He is currently professor at Aichi Shukutoku University and honorary chairman of the Shimizu Sushi Museum (Shizuoka). His publications include Sushi no Kao (Portraits of sushi; 1997); Sushi no Rekishi o Tazuneru (Following the history of sushi; 1999); and Sushi no Jiten (Encyclopedia of sushi; 2015).