This third installment in our series about sushi explores its toppings and how professional sushi chefs acquire their skills.

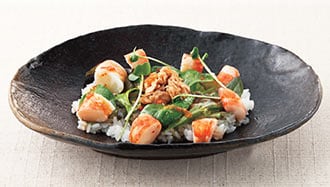

The cuisine of sushi has its own specialized vocabulary. For instance, the term neta pertains to fish and other toppings placed on sushi rice; shari is vinegared sushi rice; gariis pickled ginger. While these terms are unique to the world of sushi, they are commonly known and sometimes used in daily life. For example, the Japanese phrase “running out of neta for conversation” alludes to neta sushi toppings as conversation topics. Its origin derives from when sushi chefs use up all neta essential for making sushi during business.

The topic of toppings

The most popular neta topping these days is maguro tuna, but things were quite different when nigiri-zushi first appeared in the 1820s, a time when maguro was not so highly esteemed. Two hundred years before refrigeration, the greatest concern for a sushi chef would have been to avoid allowing fresh ingredients to go bad. Fish toppings such as trout, sea bream, shrimp, squid and others were all routinely seasoned and cured using salt or vinegar, or boiled to prevent spoiling. Maguro was considered a poorer quality fish, and very few favored the fatty maguro toro that is now in such demand. At that time, the standard way of preserving maguro was to marinate it in soy sauce, but as a topping, the soy sauce-steeped fish was sure to stain the white sushi rice it was placed on—something prominent sushi chefs were reluctant to do. Certainly no maguro-topped sushi are visible in a well-known painting of nigiri-zushi by Japanese artist Kawabata Gyokusho, titled Yohee Sushi (ca.1870), referring to the name of a popular sushi shop in the late nineteenth century.

Not until refrigerators became part of the urban scene in the late 1920s and early 1930s were fresh sushi toppings used without curing or boiling. As refrigeration technology advanced, freezing and chilling functions became available. The quality of toppings also improved and options like ikura salmon roe and uni sea urchin were added, which would have been unimaginable in earlier times. Refrigeration opened up a whole new era of sushi.

Path of a sushi chef

Traditionally, an aspiring sushi chef would not make sushi from the outset, but would enter into an apprenticeship and start by washing dishes and making deliveries. By accompanying the master chef to the market to select neta ingredients, the apprentice would learn to recognize the freshness and quality of fish, and observe the procedures for dressing, filleting and slicing the toppings. The techniques of cleaning and filleting fish are diverse: they vary from one season to another and depend upon the area where they are caught, as well as the stage of the fish’s lifespan. It would be at least three years from the start of an apprenticeship before an aspirant was allowed to fillet fish for the first time. Even then, fish filleted by apprentices would not be served to customers. As part of their lessons, an apprentice would first learn how to use ingredients without waste by cooking leftovers from filleting or slicing neta toppings to make soups and meals for the kitchen staff.

The traditional training of an apprentice takes years, as summed up by the saying, “rice cooking for three years, nigiri-making for eight years,” meaning that it could take three years until a novice learned to cook rice properly to the satisfaction of the master chef, and only then would the trainee move on to making vinegar seasoning for sushi rice. The apprentice would gradually acquire all the skills for tasks relating to a sushi shop, from communicating with customers and business management, to cleaning and odd jobs. Indeed, the training of a professional master sushi chef has no defined goal or completion date, and continues throughout his lifetime. The craftsmanship of a sushi chef—which arguably could be defined as an art—is difficult to fully explain. Trainees are not formally “taught”; rather, they make their way by picking up skills from the master chef and senior trainees. Techniques are not explained explicitly, leaving the aspirant to discover what must be learned through hands-on experience and close observation—a process referred to as “stealing” the master’s secrets. In recent years, young people are less willing to accept this often difficult-to-understand traditional style of training. It is unsurprising that the number of sushi shops in Japan has decreased by more than half, from 45,105 in 19961 to 19,122 in 2021.2

The world of a chef

Despite this decrease in the number of sushi shops, the figures for those employed in sushi establishments rose from 219,700 in 19961 to 254,523 in 2021.2 This phenomenon appears to reflect a shift from small-scale sushi shops with one master chef and one or two trainees to largescale restaurants where dozens of chefs are making the sushi. More significantly, it also likely signals a simplification of the training process. There are now schools where students are taught how to make nigiri-zushi, making it possible to acquire these skills in a short time—for some, in as quickly as one month. There have been cases where younger people, including non-Japanese, have graduated from such schools to successfully open popular shops, some of which have been highly rated in prestigious restaurant guides.

If the making of sushi is defined as simply putting rice and neta toppings together, it certainly does not take years to master. A skillful person can pick up the technique in a matter of two weeks and obtain qualifications to work in a kaiten conveyor belt-style sushi restaurant. Kaitenzushi work does not involve direct contact with customers, so chefs there do not have to acquire skills in understanding and consideration for individual customers. Yet the traditional Japanese sushi shop is not merely a place to eat sushi; it is a place where the chef serves sushi to customers directly over the counter while engaging in conversation. Through communication and observation, an experienced chef can anticipate and cater to a customer’s individual preferences and appetite as the meal progresses, while customers acknowledge and appreciate the chef’s thoughtful, intuitive service. From the very moment a customer enters the shop, the chef endeavors to create the best possible dining experience. The training of a sushi chef never ends; for indeed, sushi embodies the fine art of hospitality.

- 1Establishment and Enterprise Census 1996 (Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications)

- 2Economic Census for Business Activity 2021 (Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications)

Terutoshi Hibino was born in 1960 in Gifu Prefecture. He received his BA and MA degrees from Nagoya University, and his PhD in Japanese Culture from Aichi University. He is currently professor at Aichi Shukutoku University and honorary chairman of the Shimizu Sushi Museum (Shizuoka). His publications include Sushi no Kao (Portraits of sushi; 1997); Sushi no Rekishi o Tazuneru (Following the history of sushi; 1999); and Sushi no Jiten (Encyclopedia of sushi; 2015).