This second installment in our series on sushi focuses on its diverse regional variations and long associations with ritual and celebration.

The word “sushi” is said to have derived from the Japanese word for “sour.” The earliest type of sushi was made by souring fish and rice through fermentation; eventually, vinegar came to be mixed with rice, and this became the mainstream method for attaining the characteristic sour taste of sushi. For many, sushi is synonymous with nigiri-zushi: vinegared sushi rice topped with seafood. In fact, sushi styles and techniques vary by region. Not only can it be shaped by hand into nigiri-zushi, it can be pressed into molds, formed into rolls or mixed with rice and other ingredients that may include regional specialties—anything from raw fish to vegetables to pre-prepared dried products. It is tradition in Japan to serve special sushi on celebratory occasions such as religious and seasonal events and during ceremonies and festivals.

Ritual and tradition

In ancient times, special foods were prepared as offerings to the deities. Following rituals, these foods would be removed from the altar and shared among those involved. In many regions, sushi has long been regarded as one such offering. At Miwa Shrine in Shiga Prefecture, for example, a ritual offering of fermented loach and catfish sushi continues to be a strictly prescribed local tradition, as is whole-fish Japanese barracuda sugata-zushi, offered at Shimakatsu Shrine in Mie Prefecture. Because these particular types of sushi are crucial elements in shrine rituals, they are more likely to be perpetuated for as long as those rituals are practiced in their respective communities.

Apart from rituals, various region-specific sushi dishes are traditionally prepared for annual festivities. During the New Year in Hokkaido and the Tohoku and Hokuriku regions along the Sea of Japan, it is customary to prepare particular types of preserved sushi called izushi, made by fermenting local fish with rice, rice koji and vegetables. In Kochi Prefecture, sawachi-style platters of assorted delicacies, which include various types of regional sushi, are common during similar festive occasions. The western part of the country boasts the most varieties of sushi made at home, including the “scattered” or rolled types, as well as inari-zushi (sushi rice stuffed in deep-fried tofu pouches). Also popular in western Japan are pressed sushi such as box-pressed hako-zushi and rectangle-shaped bo-zushi formed using a leaf wrap. These, like most regional sushi, showcase local seasonal fish.

Nationally recognized favorites

These days, the only traditional celebrations where sushi preparation is de rigueur throughout Japan are probably the Hinamatsuri doll festival in March and Setsubun, a ritual in February to mark the last day of winter on the lunar calendar. For Hinamatsuri, also called Girls’ Day, a dish called chirashi-zushi (“scattered sushi”) is served; on Setsubun, the signature dish is ehomaki thick sushi rolls, eaten uncut to bring good fortune. The origins of these customs are regional in nature: chirashi-zushi is said to have originated in eastern Gifu and northeastern Aichi prefectures, while ehomaki may have sprung from the Hanshin Osaka-Kobe area. In recent years, these two customs have become commercialized throughout the entire country.

Some longtime regional favorites marketed as souvenirs have become well-known and popular nationwide. There are those named after cities, including Iwakuni-zushi from Yamaguchi Prefecture and Omura-zushi from Nagasaki Prefecture, both large box-pressed sushi. Others are sold year-round as regional delicacies, among them bara-zushi, a scattered-sushi mixed with ingredients from the Bizen region in Okayama Prefecture. Another is box-pressed kakinoha-zushi from the Nara area, which features fish on sushi rice wrapped in persimmon leaves. Both kakinoha-zushi and bara-zushi can trace their origins as festive foods once enjoyed for celebrations.

Cultural heritage

Regional sushi dishes are deeply rooted in their regions, and are commonly shared at large gatherings among families and communities. Their unique traditions and preparation methods have been passed down and sustained from generation to generation. Nevertheless, some of these sushi dishes are in fact facing some challenges as to whether or not they will be carried on into the future. They often require intensive preparation, and modern households may find it difficult to spare the time. Local festivals and traditional events in Japan have changed drastically in recent years, and some are noticeably less lively and enthusiastic. While some community efforts do exist that aim to protect these culinary traditions, it can arguably be claimed that region-specific sushi has become something of an intangible cultural heritage.

Personal celebrations

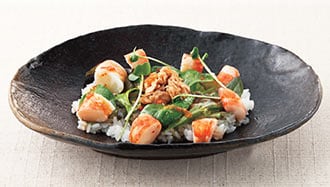

Today it is commonly observed that many of the distinctive foods usually consumed on traditional occasions are being simplified, purchased or catered, rather than made at home— and sushi is no exception. At the same time, we see a trend where younger generations are enjoying casual, more creative dishes, including sushi made for personal celebrations. One popular choice for home parties, for example, is temaki-zushi, where participants wrap sushi rice and their favorite fillings in sheets of nori seaweed right at the table. At wedding receptions and anniversaries, people prepare the celebrants’ favorite type of sushi, or order special sushi platters from restaurants. Consequently, the role of sushi is expanding from being a general indicator of regional identity to a dish that also emphasizes individuality.

Ultimately, sushi remains a much-loved part of the Japanese diet. Ingredients and styles may change, and its role may be evolving, but whatever its form, whatever the occasion, sushi evokes a comforting sense of warmth, connection and harmony.

Terutoshi Hibino was born in 1960 in Gifu Prefecture. He received his BA and MA degrees from Nagoya University, and his PhD in Japanese Culture from Aichi University. He is currently professor at Aichi Shukutoku University and honorary chairman of the Shimizu Sushi Museum (Shizuoka). His publications include Sushi no Kao (Portraits of sushi; 1997); Sushi no Rekishi o Tazuneru (Following the history of sushi; 1999); and Sushi no Jiten (Encyclopedia of sushi; 2015).