In the third part of our series on the traditional plant-based cuisine of shojin ryori, we examine how this food is served in Buddhist temples in Japan.

In Japan, many zazen seated-meditation halls, known as Zen dojo, are situated within the precincts of Buddhist temples. Novice priests entering the Zen Buddhist order are assigned to one of several organizational divisions within the temple, where they assume specific duties. These divisions may include reception, visitor guidance, inventory management, Buddhist services, zazen supervision, and, invariably, kitchen duty. The kitchen division of a temple is referred to as the tenzoryo, taking its name from tenzo, the person who supervises all kitchen activities.

Serving Buddha

Those priests serving in the temple kitchen prepare a number of different meals. The foremost of these are the offerings: a tray of dishes presented to the principal image or statue of Buddha at the temple, and to the deceased. The kitchen staff arise at first light of dawn, so as to have these offerings laid at the altar before the rest of the priests awaken and assemble for morning prayers. Of course, the Buddha does not actually consume the meal, but it makes no sense for this offering to be simply a decorative formality. As part of their training in Zen practice, the priests prepare what they consider the best possible dishes as an act of piety, dedicated to the being in whom they place their faith and highest respect. After morning services conclude, the tray is taken down from the altar and the highest-ranking priest consumes it in place of the Buddha.

Serving guests

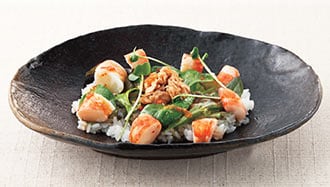

Kitchen staff then prepare meals for visiting worshippers and guests, some of whom may include high-ranking priests from other temples. These meals are served on elevated lacquered tray-tables, and comprise assorted dishes that include simmered and/or dressed seasonal vegetables. Close attention is paid to their appearance and detail, so as to express hospitality and convey respect. The centerpiece of these guest meals is goma-dofu, sesame tofu, which is made in a series of deliberate and meditative steps: first, sesame seeds are carefully toasted to bring out their aroma, then ground with mortar and pestle into a very fine powder, which usually takes about an hour. Kuzu starch and kombu dashi stock are added to the powdered sesame. The mixture is stirred for another hour in a large pot over low heat as it forms a thick, smooth consistency; it is then poured into a mold and cooled in water overnight. It is finally cut into squares and served with miso sauce and grated wasabi.

While performing the time-consuming processes of grinding and stirring, if the cooks are distracted by unrelated thoughts brought on by fatigue, the goma-dofu may lack the proper consistency, so that it cannot be cut into clean shapes. Beautifully shaped blocks of goma-dofu result only if the cooks concentrate wholly on their work with the same clarity as if they were practicing zazen in their formal robes. Goma-dofu made by a master cook has a firm set shape, yet is very soft and viscous; it yields easily when divided with chopsticks. As soon as it enters the mouth, goma-dofu dissolves and releases the rich flavor of sesame.

After removing goma-dofu mixture from the pot, the cook is careful to scrape out any remnants and set them aside. These, along with vegetable trimmings from the preparation of other dishes, are used to make goma-ae, a vegetable dish dressed with seasoned ground sesame. Often, it is the food peels and trimmings that contain the greatest concentration of nutrients, and these can be made into tasty dishes that reveal no hint that they were leftovers. One of the characteristics of shojin ryori is that very little waste remains.

Serving priests

Finally, most food made in temple kitchens is prepared for the daily meals of the priests. In very large Zen practice halls-at the head temple of a particular school of Buddhism, for example-there may be several hundred mouths to feed. In contrast with those meals served to guests, daily temple fare is composed of only a few very simple dishes, with little attention paid to appearance; yet one can find a refined beauty in these practical, day-to-day meals.

Typical menus might be as follows: for breakfast, rice porridge (okayu), a mixture of salt and sesame seeds as a topping, and a side dish of pickles; at midday, steamed rice mixed with barley (mugimeshi), miso soup, pickles, and one or two side dishes; and for the evening meal, steamed white or mixed rice, miso soup and pickles, accompanied by a few additional dishes. The type and number of dishes vary according to services being performed on a particular day.

Utensils and etiquette

When dining, priests use oryoki, a nested stack of five to seven bowls of varying sizes. Each priest has their own stack of bowls. These are usually of lacquered wood, and are wrapped up in a cloth with chopsticks, a spoon, and a spatula. At mealtime, the priest unfolds the cloth and places an appropriate amount of food into each bowl. The term oryoki connotes a bowl that corresponds to the appropriate amount of food-or “just enough”-for one person, with no waste. The word itself combines the characters for “receive (just enough),” “amount” and “vessel.”

Before beginning to eat, the priests chant a sutra that commits them to respect the food of which they are to partake, gratitude to those who have prepared it, and a sense of indebtedness to all things in the world. It calls on them to reflect whether, by their actions and behavior, they are worthy of receiving the meal before them, and reminds them that they eat, not to satisfy mere desire, but to maintain their health sufficiently to pursue training.

Zen table manners for priests are very intricate and are expected to be strictly observed. Details extend to every aspect of the meal: the movements and position of one’s fingers handling the bowls, the way chopsticks and spoons are held to bring food to the lips, how the wrapping cloth should be folded, the pace of eating, and sounds permitted while eating. At the end of the meal, a small spatula is used to meticulously scrape out any remnants of food that may be left in the bowls. These are consumed, thus ensuring that there is absolutely no waste. It usually takes about one month for priests-in-training to master these forms.

The etiquette for temple meals is elaborated in Fushuku Hanpo, “The Dharma of Taking Food,” written by Zen master Dogen, the first abbot of Eiheiji Temple. It instructs priests to put on formal robes and sit in the zazen meditation posture during meals, as eating itself is regarded as an important form of training. It calls for asking yourself what you can do to serve others, using the energy received from the food. For priests, each meal is a scene for reflection and renewal of their commitment to the precepts to which they are pledged. In this sense, therefore, preparing food, as well as consuming it, is integral to Buddhist instruction; these activities are not merely processes or tasks, they are training in the true sense of the word, as reflected in the phrase, “Zen training in the kitchen.”

Shoshi Takanashi was born in 1972. Currently head priest at Soto Zen temple Eifukuji in Gunma Prefecture, he is also a specialist in shojin ryori and studies the spirit and techniques of this cuisine. From 2001-2005, he served at Daihonzan Eiheiji Tokyo Betsuin Chokokuji Temple, where he was tenzo (head of kitchen). His publications include Hajimete no Shojin Ryori: Kiso kara Manabu Yasai no Ryori (Beginner’s guide to shojin ryori: basics of vegetable cooking; 2013).