As our series about shojin ryori concludes, we look at how this Buddhist culinary tradition has been incorporated into daily home cooking.

One of the virtues to which Buddhist priests adhere is the practice of sharing. Money, food and other resources are shared freely with others, rather than hoarded. This principle applies not only to material things, but also to teachings and knowledge. Whatever is deemed to be good is to be distributed or disseminated openly and proactively, not concealed or hidden away. Priests use various ways of extending what they have learned to society: the serenity attained through their practice, for example, or teachings found in sutras.

Shared experience

In the same way, knowledge of shojin ryori, although originally created and refined by priests in Zen temples for their own training and spiritual cultivation, was shared beyond temple walls with ordinary people. When people visited temples to hold ceremonies for the deceased or offer prayers to the principal deity, shojin ryori was sometimes served to them, providing a rare opportunity to experience dishes that were unfamiliar to the masses. Furthermore, from the Muromachi period (1336-1573), temples in the Soto school of Zen Buddhism around Japan actively promoted lay participation in monastic practice, wherein laypeople would stay at a temple for several days to join priests in zazen meditation and the chanting of sutras. Temples made efforts to transmit the fundamentals of the monastic way of life to them so they could follow these practices upon their return home.

Historically, these temple training experiences have also included instruction in the manners and practices of the temple kitchen and its methods of food preparation. If such experiences had been related to a business enterprise, these kitchen secrets would surely have been hidden. But in their adherence to the precept that what is good should be shared with all, temples allowed shojin ryori to spread to all people—and into their kitchens.

Shared tastes

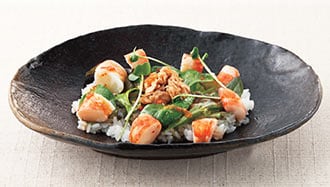

It is difficult to describe with certainty how some modern cooking methods and dishes might be traced directly to shojin ryori. It is said that techniques such as deep-frying and stir-frying were acquired by Japanese priests studying in China who brought this knowledge back to temple kitchens in Japan, where it adapted to Japanese cooking styles. Indeed, many dishes typically associated with today’s Japanese home cooking share similarities with the classic shojin ryori repertoire: popular deep-fried vegetable tempura, for instance, is said to have originated from shojin ryori.

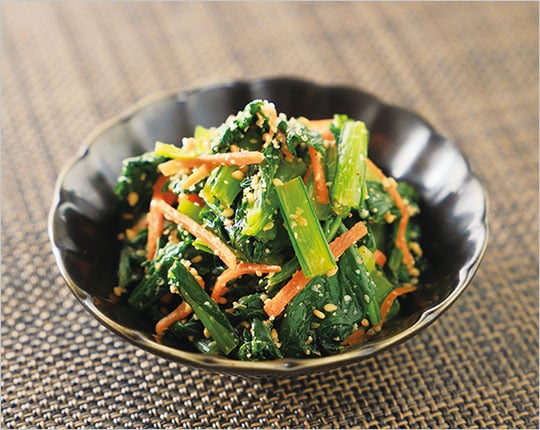

Connections between temple food and household cooking might be suggested by the names of some dishes. One example is kimpira gobo, a side dish usually made with sauteed root vegetables that is often found both on Japanese tables and routinely prepared in temples. Burdock root (gobo) and carrot are sliced into thin strips, stir-fried in oil and seasoned with soy sauce and mirin, with chili pepper added for a touch of heat. There are several theories regarding the origin of the name kimpira gobo. One intriguing explanation suggests it is a play on words: Kompira-sama is a guardian deity worshipped at temples, while gobo refers not only to burdock root, it can also mean a temple building or priest. Another dish possibly referencing shojin ryori is the commonly served aemono, which involves assorted vegetables combined and dressed with ground sesame seeds or tofu. The written kanji characters for aemono carry the idea of “bringing things together,” which reflects Buddhist teachings of unity and harmony.

Shojin ryori is considered the likely inspiration behind kenchin-jiru, a hearty soup of tofu and root vegetables that is a favorite in home kitchens. One well-known anecdote about the origin of the soup involves a priest in training who accidentally drops a block of precious tofu, reducing it to crumbles.* Kenchin-jiru is prepared by crumbling and dry-roasting tofu, then simmering it with kombu and vegetables that often consist of trimmings, peels or leftovers from the preparation of other dishes. The texture of dry-roasted tofu resembles meat, which is prohibited in temples. In former times, meat was a rare and inaccessible ingredient for ordinary households, and this meatless substitute became popular beyond temple walls among the wider populace. This thrifty use of broken pieces of tofu and kitchen scraps embodies the spirit of shojin ryori.

Shared gratitude

At the heart of shojin ryori, one is taught to approach ingredients with care and reverence in a manner that honors the life-giving spirit of precious food. In Zen temples, before and after meals, priests chant sutras of gratitude; these are directed both toward the food itself and to those who prepared it. As they partook of temple meals, both visitors and laypeople in temple training absorbed this spirit of gratitude, and over the course of centuries, priests propagated this underlying meaning. One could say that the commonly used Japanese expressions itadakimasu (“I humbly receive”) and

gochisosama (“thank you for the meal”) are simplified forms of this tradition of expressing gratitude. Even today, many Japanese place their hands together in the Buddhist gesture of reverence, reciting these phrases before and after a meal.

The origin of many Japanese dishes that are routinely prepared in households can be traced to shojin

ryori and, as it attracts renewed attention as exemplifying a healthy and balanced diet, contemporary adaptations continue to emerge. Even when shojin ryori was first created in Zen temple kitchens, a similarly experimental approach was taken in devising new dishes, and so modern innovations are entirely in keeping with the spirit of this cuisine. Japanese cuisine evolved around the skillful use of vegetables and the ability to bring out their subtle flavors using delicate seasonings such as dashi and soy sauce; such attributes are deeply rooted in the teachings and techniques of shojin ryori.

I believe shojin ryori has played a part in enriching Japanese cuisine. Placing one’s hands together and humbly expressing gratitude toward the food, toward those who prepare it, and to our very own life that allows us to partake of the meal itself—these all embody a spirit that I sincerely hope will be passed on through future generations as an essential part of Japan’s food culture.

* This anecdote, passed down in Zen temples, is one of several theories regarding the origin of kenchin-jiru.

Shoshi Takanashi was born in 1972. Currently head priest at Soto Zen temple Eifukuji in Gunma Prefecture, he is also a specialist in shojin ryori and studies the spirit and techniques of this cuisine. From 2001-2005, he served at Daihonzan Eiheiji Tokyo Betsuin Chokokuji Temple, where he was tenzo (head of kitchen). His publications include Hajimete no Shojin Ryori: Kiso kara Manabu Yasai no Ryori (Beginner’s guide to shojin ryori: basics of vegetable cooking; 2013).